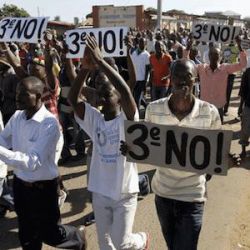

The fragile Great Lakes region of central Africa has been thrown into turmoil over the the past few days. Police unleashed violence against protesters in Burundi after the current president, Pierre Nkurunziza announced on Saturday, 25 April, that he intends to run for a third term as president. This unconstitutional move is undermining the Arusha Peace Agreement, which ended the 13 year civil war. It risks pushing the entire Great Lakes region into chaos and instability, and a possible return to another war.

According to the constitution of Burundi, the president is only allowed to stand for two terms of 5 years each. But the current president, Nkurunziza, a former rebel leader, and his CNDD-FDD party, argues that he is eligible to stand in the June 26 poll because he was chosen by legislators in his first term of office and not voted in by the public. But this flimsy excuse did not convince many people.

On Sunday, 26 April, thousands of people protested the decision of Nkurunziza in the capital city Bujumbura. However, the demonstrations were immediately attacked by the police. At least three people were killed on Sunday as police shot live ammunition into the crowds. In addition, media reports also indicate that a further three people were killed by CNDD-FDD's Imbonerakure youth wing. Dozens more have been wounded. In other areas protesters have erected roadblocks and barricades where they have been demonstrating. Police have also fired tear gas and water cannons at the protests. This prompted demonstrators to disperse temporarily only to regroup elsewhere.

The government has banned public protests and demonstrations, fearing an uprising. But the crackdown has not deterred the protesters, who have defied the bans and remained in the streets. On Monday, 27 April, hundreds of youth erected barricades and set alight tyres in Bujumbura. “The fight continues’’, they chanted. A fierce battle then ensued with the police when the protesters tried to march on central Bujumbura from the Cibitoke district north of the capital. Several other protests also erupted across the city. According to a senior police official at least 320 people have been arrested.

The current protests come on the back of recent mounting discontent. On 5 March a general strike shut down most of Bujumbura. The strike protested high fuel prices, high mobile phone bills and a proposed telecoms tax. Public transport in the capital ground to a halt, paralysing all government services. Tharcisse Gahungu, chairman of Burundi's Confederation of Trade Unions (COSYBU), told Reuters: "International fuel prices have significantly fallen, but we don't see any change. We want the government to adjust local fuel prices at the level of current price of a barrel on the international market. Additionally, we demand the cancellation of a new tax on mobile telephones, because the mobile telephone in Burundi is no longer a luxury product, but a useful tool for most people in their everyday life."

The current protests come on the back of recent mounting discontent. On 5 March a general strike shut down most of Bujumbura. The strike protested high fuel prices, high mobile phone bills and a proposed telecoms tax. Public transport in the capital ground to a halt, paralysing all government services. Tharcisse Gahungu, chairman of Burundi's Confederation of Trade Unions (COSYBU), told Reuters: "International fuel prices have significantly fallen, but we don't see any change. We want the government to adjust local fuel prices at the level of current price of a barrel on the international market. Additionally, we demand the cancellation of a new tax on mobile telephones, because the mobile telephone in Burundi is no longer a luxury product, but a useful tool for most people in their everyday life."

Toxic atmosphere

The general mood is a desperate desire for the masses to change their conditions, which they can no longer endure. This poses a direct threat to the corrupt rulers who have a very thin base amongst the mass of people.

In the latest upheavals, the government initially reacted with hysteria. Nkurunziza’s spokesperson called the protests ‘’an insurrection’’. Reuters reports that government ministers and the police shut down radio stations critical of the government and intimidated others into silence. After the initial crackdown by the police, the army was then deployed on the streets. But instead of firing on the protesters, the soldiers marched alongside the demonstrators. In some instances the soldiers even prevented the police from attacking the protests. This action by the soldiers on Monday has also had the additional effect of keeping the Imbonerakure away from the demonstrations.

The actions of the army prompted some to speculate that the soldiers have moved over to the side of the demonstrators. However, the situation is more complex. The Burundian army is an amalgamation of different fighting units which once fought against each other. Many of the fighting units have different loyalties. Not all are consolidated under the control of the president. For example, the defence minister, Pontien Gaciyubwenge, flatly disobeyed Nkurunziza’s call to integrate the armed elements of the Imbonerakure into the military.

Mounting tension or clashes could split the army, which was transformed from a Tutsi-led force to one that absorbed rival ethnic militias. Some soldiers might find loyalties strained if ordered by the government to intervene. This leaves open the spectre of a return to armed conflict.

As opposed to the army, the police (which is headed by Adolphe Nshimirimana, a close advisor of the president) is under the tight control of the president. The actions of the police in the current situation demonstrates this. They were directly involved in the crackdown of the protests, as well as on the media.

For years, Burundi has been marked by a climate of political tension that frequently degenerates into violent incidents. In the last period, there was talk that the youth wing of the ruling CNDD-FDD party, the so-called Imbonerakure, had been receiving military training in the DR Congo and has been involved in extra-judicial killings of political opponents. These youths have increasingly been used as a paramilitary force to intimidate and silence critics of the government. This militia force has been operating more and more aggressively and with complete impunity.

In February this year, this militia group was involved in the extra-judicial killings of 47 fighters who has crossed the borders from the Congo, and who have been engaging in a firefight with the Burundian Army. According to Human Rights Watch, members of the

Imbonerakure who were captured were not treated as prisoners of war but were killed, either by shooting, by being beaten to death, or by being thrown off a cliff. Now these Imbonerakure members are directly involved in cracking down on protesters in the capital. All of this has created a toxic atmosphere in Bujumbura.

Thousands of people have already fled across the border to Rwanda, fearing attacks and reprisals from the Imbonerakure. The UN Refugee Agency says Burundians are fleeing at a rate of 3000 per day, up from 500 per day last week. Tanzania also expects a big influx of refugees if the situation in Burundi worsens. The developing situation risks destabilising the already fragile Great Lakes region.

Burundi is one of the poorest countries on Earth. Agriculture accounts for over 40 percent of GDP and employs more than 90 percent of the population. The country is heavily dependent on bilateral and multilateral aid as a direct result of a series of ‘’structural adjustment programs’’ from the IMF which attempted to reform the foreign exchange system, liberalize imports, reduce restrictions on international transactions, diversify exports, and reform the coffee industry. These programs have plunged the already impoverished and war-torn country into into an unmitigated disaster.

Imperialist legacy and the Arusha peace agreement

The crisis in the Great Lakes region is a direct result of the criminal imperialist policies which sought to loot the immense wealth of the region. This has been done through dividing the people of the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi along ethnic lines. Just like Rwanda, Burundian politics had been shaped by ethnic divisions and the legacy of colonial and imperialist policies. The crisis in Burundi cannot be detached from the general crisis in the Great Lakes region. These in turn, have their origins in the policies of both German and Belgian colonialism which deliberately played off the Tutsis against the Hutus, granting the Tutsi minority the top administrative posts. This was a classic ‘’divide and rule tactic’’ employed by the imperialists with devastating consequences for the entire region to this day.

During the colonial revolution after the Second World War, the Rwandan National Union pressed for independence from Belgium. This meant that Belgian support for the Tutsi minority began to wane. The Belgian government then set up the Party of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Bahutu, sparking communal strife with the Tutsis as a way of keeping its grip of the situation. In 1959 there was a war in which the Hutus drove out the Tutsis. Rwanda was declared a Hutu republic in 1962. A parallel situation developed in Burundi where the Hutus were suppressed. The Tutsis in Burundi attacked Rwanda in 1963. This resulted in 250,000 refugees, mostly Tutsi, living in DR Congo, Uganda and Burundi. After the countries of the Great Lakes received their so-called independence, all of them were immediately confronted with mass displacements of Hutus and Tutsis with the resultant deep ethnic divisions.

This situation got even worse when France intervened in Rwanda in 1990 and 1993 to prop up the Hutu government of Juvenal Habyarimana. Then, the mainly-Tutsi opposition Rwandan Patriotic Front invaded Rwanda and drove away government troops and its allied Interahamwe militias which had engaged in genocide and the murder of more than 800,000 Tutsis. This created a massive refugee crisis in all countries including Burundi. It is therefore ironic that many refugees are now fleeing back from Burundi to Rwanda. The humanitarian disaster and the mass displacement of the people is therefore a direct result of imperialist meddling.

Over last three decades French imperialism has lost much of its influence in Francophone Africa. This is also true of the Great Lakes region. Their role has increasingly been replaced by US Imperialism. After the 1994 Rwandan genocide, the Americans swiftly intervened in the region under the guise of ‘’humanitarian aid’’. After watching the wholesale slaughter of hundreds of thousands of people in Rwanda, Bill Clinton, crying crocodile tears, swiftly wanted to stabilise the region for the sake of American business. This was the basis for the Burundi Arusha Agreement of 2000 which ended the war.

Pierre Nkurunziza came to power in 2005 after leading a rebel group during the country’s 12 year civil war. The Arusha Agreement, which was agreed under the direct influence of US Imperialism and the government of Thabo Mbeki, the then South African president, eventually brought an end to the war which killed more than 300 000 people. But on the basis of capitalist and imperialist domination nothing was solved. This is actually what is responsible for the current crisis.

Crossroads

If the current conflict escalates, there is real possibility that it could have regional consequences. A big refugee stream between Burundi, Rwanda and the Congo could encourage Rwanda and Congo to make incursions which could spark a regional conflict. Already the government of the DR Congo launched a military offensive against Rwandan FDLR rebels earlier this year. Further unstable refugee flows could prompt the Congo to intervene in Burundi. This just shows how fragile the whole Great Lakes region is. Events in one country have an immediate impact on other countries in the region.

But this does not only apply to war. It also applies to revolutionary mass movements. Over the last period there have been mass movements breaking out in one African country after the other. As indicated earlier, the current protests against term limits has its origins in the movement of the masses around social issues and poor living conditions. In other words, the masses clearly see the the path to democracy as part of a general movement to improve their lives.

The protests in Burundi also come on the back of protests earlier this year in the neighbouring DR Congo when the students successfully prevented Kabila from standing for another term as president. This has been the theme across much of the continent, especially West Africa, where the revolution in Burkina Faso served as inspiration to the masses and the youth across the continent. But as we explained, the conflict in the Great Lakes region is part of the same problem. The borders of many of these countries are complete arbitrary constructs of the imperialists.

The success of these movements will therefore depend on whether they can combine to fight a common struggle against their oppressors. This means a struggle against not only the local leaders, but their imperialist masters. But most of all the success of the struggle will depend on escalating the movement into an all-African revolution led by countries with big working class populations like Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt.