The following is an introduction by marxist.com editor Fred Weston to the new edition of The First Five Years of the Communist International from Wellred Books (buy it now!) Fred outlines some of the key debates and decisions taken in the first four congresses of the Communist International. This, we hope will serve to place the contribution of Trotsky into the context of the period.

Trotsky’s texts, together with the main documents of the first four congresses of the Communist International, should be read and studied carefully by all workers and youth who are seeking a revolutionary way out of the present crisis of capitalism, as they are full of deep insights on the flow of history itself.

The republication of The First Five Years of the Communist International comes at an opportune time, when capitalism is facing the most serious crisis in its whole history. The capitalist world is hurtling towards disaster and this is being felt by billions of workers and youth across the world, who are asking questions about the very future of this system.

There is no way out of this crisis unless the root cause is tackled head on: the capitalist system itself. Unless it is removed, it will continue to condemn humanity to growing poverty, hunger, and war. To achieve this, what is required is an international organisation of the working class, with a clear understanding of the nature of the crisis we face.

The last time a truly mass revolutionary international organisation of the workers existed was shortly after the First World War when the Communist International was created. Its aim was the socialist transformation of the whole world.

We, the genuine Marxists who base ourselves on the ideas of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky, recognise the first four congresses of the Communist International as genuine forums of Marxist debate, where most of the questions we still face today were hammered out. The resolutions and theses voted at those congresses are a heritage we claim as ours. The debates and speeches of the key leaders are also of extreme relevance today.

Two leaders stood out above all the others, Lenin and Trotsky. Much rewriting of history, with lies and distortions, has been carried out since then. The Stalinist bureaucracy in the Soviet Union falsified the role Trotsky had played in the Russian Revolution. The reason for that was that he continued to defend the genuine ideas of Bolshevism, which were a direct threat to the privileges and power that the bureaucracy had acquired in the course of the 1920s.

In 1924, however, Trotsky was still recognised as one of the key leaders of the Communist International and the Soviet Union. Testimony to that is the fact that the present collection of texts was published by the official state publishing house in Moscow in 1924. We are making it available once more, at a time when the urgent task facing the workers of the world is to build a mass revolutionary international organisation like the Communist International.

Wellred books

Introduction

The Communist International came into being in 1919. It gathered various forces, some of which were mass parties, some were small groups striving to become parties, and some were currents moving in the direction of revolutionary Communism. What provided the impetus towards the formation of the new International was the wave of revolution that swept the world at the end of the First World War, at the heart of which was the October Revolution in Russia in 1917. The success of the Bolsheviks in leading the workers to power provided the focal point around which the Communist International rallied.

It was for this reason that the two outstanding leaders of the Russian revolution, Lenin and Trotsky, also played a key role in the building of the new International. Lenin’s role is unquestionable, but Trotsky’s has been somewhat blurred by subsequent events. Lenin died too early to witness the bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union and the rise of the monstrous Stalinist regime – although he had an inkling of what was beginning to crystallise, as his last letters clearly demonstrate. It, therefore, fell to Trotsky to defend the real heritage of Lenin; his ideas and methods of work.

With the objective development of events: the defeat of one revolution after another that led to the isolation of the Soviet Union, which had inherited the backward economic conditions left by the Tsarist regime, the conditions for the rise of a privileged bureaucratic caste were prepared. It was this rising bureaucracy that used the mantle of Lenin to cover its real role, while at the same time building up a number of myths about Trotsky, all aimed at depicting him as an enemy of Bolshevism.

The articles, resolutions and speeches by Leon Trotsky made available in this book demonstrate how false the picture the Stalinists have attempted to depict was. Trotsky was a key figure throughout the first four congresses of the Communist International. What also has to be underlined is that Trotsky actively participated in each congress of the Communist International in this period, while at the same time building and leading the Red Army, which at the time was fighting the Civil War against the Whites.

Here, we will touch on the main debates that took place during the first four congresses of the Communist International between 1919 and 1922 and provide the background to the texts presented in this volume.

Why an international communist organisation was necessary

Marxists have always been internationalists. This is not for sentimental reasons, but for very concrete practical reasons. Capitalism is an international, indeed a global system and it cannot be successfully combated solely within the confines of one country.

For socialism to be successful it must spread on the international arena. The later degeneration of the Russian Revolution was to prove this in practice. The rise of the monstrous bureaucratic, totalitarian, Stalinist regime was the result of the isolation of the revolution to one country.

Marx and Engels never envisaged “national roads to socialism” / Image: Zorion

Marx and Engels never envisaged “national roads to socialism” / Image: Zorion

The founding fathers of scientific socialism (i.e. Marxism), Marx and Engels never envisaged “national roads to socialism”. In 1847, the Communist League led by Marx and Engels was an international organisation that prepared the ground for the founding of the First International in 1864 and later the Second International in 1889.

Marxist organisations, however, do not live in a vacuum, isolated from society. They are made of members who live and work in a capitalist environment and this in turn can impact on their consciousness and understanding. We saw this in the case of the leaders of the parties that made up the Second International. Based on a prolonged period of capitalist upswing, they began to draw mistaken conclusions on the nature of capitalism. They moved away from the idea that capitalism needed to be overthrown, and drew the conclusion that it could be gradually reformed. This led to adaptation to bourgeois society and class collaboration with the capitalists, and eventually to the betrayal of the principles upon which the International had been built.

August 4th 1914 was a black day in the history of the international labour movement, for that was the day when the representatives of the German Social Democratic Party voted in favour of the war credits in the Reichstag, the German parliament, together with all the bourgeois political parties.

On the same day, all the MPs of the SFIO – the French Socialist Party, as it was then known – also voted in favour of the war creditsin the French parliament. In other countries, the Social Democrats likewise supported their own bourgeoisies in the war, thus collaborating in the terrible bloodshed, where workers were pitted against workers in a fratricidal war.

This marked the de facto death of the Second International as a force for international socialism. The irony was that, in several international congresses, the Second International had sworn that they would never take part in such a slaughter and they would fight to transform the war of nation against nation into a war of class against class.

At the 1907 congress of the Socialist International a resolution on war was voted which expressed clearly that:

“In case war should break out anyway, it is their [the working classes’ and their parliamentary representatives’] duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilise the economic and political crisis created by the war to rouse the masses and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.” (Resolution adopted at the Seventh International Socialist Congress at Stuttgart, August 18-24, 1907)

Again, in an Extraordinary International Socialist Congress held in Basel, November 24-25, 1912, the same anti-war commitment was reiterated.

The members of the various Socialist, Social Democratic and Labour Parties across Europe had been educated in this fundamental idea: socialists do not support wars between different national bourgeoisies, but strive to raise the working class to an understanding that workers of all countries are brothers and sisters. The resolutions were clear: if the capitalists go to war, the socialists will endeavour to speed up the overthrow of capitalism.

When the hour of reckoning struck, however, all these principles were trampled underfoot by the leaders of these parties as they scrambled to grovel before the capitalists of their own countries. It was the greatest betrayal of the working class we have ever seen in history.

Such a degeneration of the Social Democratic leaders, however, did not emerge overnight, but was part of a long, drawn-out process. The August 4th betrayal merely brought this process into sharp focus.

It was this great betrayal that set in motion the events that were to lead to the establishment of a new “Third” international organisation of the working class, the Communist International. The organisation did not spring up readymade, however. It had to be struggled for.

By September 1914, there was already talk of the need for a new International. At its November 1914 meeting, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik party called for a “proletarian International”. The following year, in September 1915, the famous Zimmerwald conference was held, with 42 delegates attending. This was a gathering of the left wing within the Second International, among them Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin.

However, even among this more advanced layer there were plenty of vacillating elements who were not prepared to draw all the necessary conclusions. The future Communist International was to emerge from the “Zimmerwald Left”, i.e. the most left-wing and consistently revolutionary section of the delegates that gathered in that small Swiss village. At the heart of this revolutionary wing were the Bolsheviks.

Initially, the forces that remained loyal to the best revolutionary traditions of the Second International were very small. What was to give a huge impetus to the building of the new International was the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, which had an enormous impact on the ranks of the old International. Just as the Bolsheviks had emerged as the revolutionary wing of the old Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, left-wing currents began to emerge within the other parties that adhered to the Socialist International.

The First World War ended with revolution breaking out in one country after another. There was a radicalisation to the left taking place in all countries to one degree or another and the seeds of the future Communist International were being sown everywhere.

The Russian Revolution was quickly followed by the German Revolution in 1918, the Hungarian Revolution in 1919, and, as the Austro-Hungarian Empire was torn apart, revolutionary movements swept across central Europe. In Italy, we saw the “Biennio rosso” [the two red years] of 1918-20, which culminated in the Occupation of the Factories in September 1920.

Similar processes were taking place in many countries, with the most advanced activists looking to the Russian Revolution for guidance. The forces of the future Comintern were developing everywhere. In countries like Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Poland and many others, strong communist currents were growing within the working-class movement.

The First Congress gathers in March 1919

This wave of revolutions was reflected in the make-up of what was to be the First Congress of the new International. A total of 39 groups were invited, of which 15 originated inside the old Second International, initially including the whole of the Italian PSI. Other groups such as the IWW and Revolutionary Syndicalists were also invited.

What we see here is an attempt to gather together all the revolutionary currents within the international labour movement, from the left wings of the Socialist Parties to the revolutionary groups that had stood outside these parties. The new International also consciously opened up to groups in the colonial countries. This was something the Second International had neglected, concentrating mainly in the European countries. There were the beginnings of communist movements in many other countries, including China and India, which looked to the new International.

In March 1919, 51 delegates representing 34 parties from 22 countries gathered in Moscow for a four-day conference. Initially, there was some debate about whether that conference should proclaim the new Third International. The German delegates, for example, although agreeing in principle that a new international organisation was necessary, felt that more time was required to prepare for it. In the end, however, the conference declared itself as the First Congress of the Communist International, and this had a huge impact, as news of the new formation reverberated around the world.

The First Congress laid down the basic principles, issuing declarations and appealing to the revolutionary forces globally to join the new organisation. ‘The Manifesto of the Communist International to the Workers of the World‘, drafted by Leon Trotsky and adopted unanimously on March 6, 1919, is made available in this book.

The Manifesto issued a bold appeal to the workers of the world, ending with the words:

“Bourgeois world order has been sufficiently lashed by Socialist criticism. The task of the International Communist Party consists in overthrowing this order and erecting in its place the edifice of the socialist order. We summon the working men and women of all countries to unite under the Communist banner which is already the banner of the first great victories.

“Workers of the World – in the struggle against imperialist barbarism, against monarchy, against the privileged estates, against the bourgeois state and bourgeois property, against all kinds and forms of class or national oppression – Unite!

“Under the banner of Workers’ Soviets, under the banner of revolutionary struggle for power and the dictatorship of the proletariat, under the banner of the Third International – Workers of the World Unite!”

When it was founded the Comintern was still made up mainly of small forces with inexperienced leadership. But by 1921 it had spread to all the continents and gathered hundreds of thousands of members. The first four congresses of the Comintern were genuine expressions of Marxist revolutionary theory and practice, a “school of revolutionary strategy” as Trotsky described it.

Lenin on the founding of the new International

Lenin understood that, without international revolution, the Russian Revolution was in danger of being suffocated. At the Seventh Congress of the Russian Communist Party in March 1918, for instance, he explained, “…if the German Revolution does not come, we are doomed.” A few weeks later he stated, “But we shall achieve victory only together with all the workers of other countries, of the whole world…” In May he returned to the question: “… final victory is only possible on a world scale, and only by the joint efforts of the workers of all countries.”

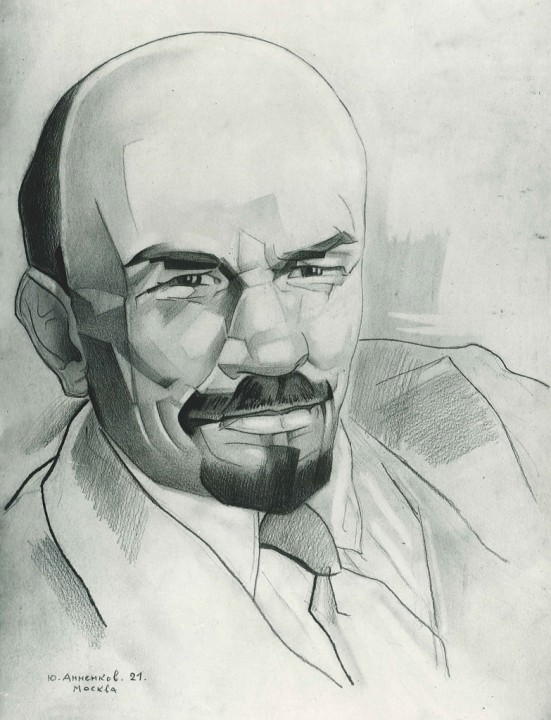

Lenin understood that, without international revolution, the Russian Revolution was in danger of being suffocated / Image: Picryl

Lenin understood that, without international revolution, the Russian Revolution was in danger of being suffocated / Image: Picryl

In his text ‘The Third International and Its Place in History‘ (15 April 1919) Lenin wrote:

“For the continuance and completion of the work of building socialism, much, very much is still required. Soviet republics in more developed countries, where the proletariat has greater weight and influence, have every chance of surpassing Russia once they take the path of the dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Lenin never gave up this view, to the very end of his life. For Lenin, the very essence of the Communist International was to provide the necessary revolutionary leadership in all countries as a means of achieving world revolution. The potential for such a revolution was seen across the globe in many countries. Lenin placed particular importance on the ongoing revolutionary events taking place in Germany.

The birth of the German Communist Party

Germany was the country with the biggest and most developed party of the Second International, the SPD. It had been looked to as a beacon by socialists around the world, including Lenin. It was also where the betrayal on the part of the SPD leaders highlighted how far that party had degenerated. Within the SPD, the divisions between the various currents – from the openly class-collaborationist elements to the revolutionary wing – went back many years. But the 1914 betrayal accelerated the process of inner differentiation.

By April 1915, the “Internationale Group” had begun to organise the revolutionaries within the SPD. These were later to be known as the Spartacists. Two years later, the SPD suffered a mass split to its left which led to the creation of the USPD, the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany, which the Spartacists later joined, providing it with the necessary revolutionary backbone. This would then become the basis for the formation of the German Communist Party, the KPD, in the hothouse of the post-war German revolution. The KPD eventually emerged as a clearly identifiable revolutionary party to the left of the SPD.

The betrayal on the part of the SPD leaders, together with the relative weakness of the Communists, however, led to the defeat of 1919, which in turn prepared the conditions for a reactionary bourgeois counter-offensive in 1920 in the form of the Kapp Putsch. But as we have seen many times in history, this whip of the counter-revolution provoked an equal and opposite reaction on the part of the working class. The general strike that paralysed Berlin was an indication of this.

A polarisation of society was taking place, with revolution and counter-revolution marching together, a situation that could only end with the total victory of one or the other. In such a situation, processes that would normally take years or even decades to unfold were moving at breakneck speed.

For example, the USPD had 300,000 members in March 1919, but one year later, in April 1920, it had jumped to 800,000 members. At its Halle congress in 1920, the USPD accepted the “Twenty-one conditions” of the Comintern and came out in favour of affiliating to the new International, fusing with the KPD. In the process, the right wing of the USPD split away. The new party adopted the name of the United Communist Party of Germany, and had 500,000 members, making it the biggest Communist Party outside of the Soviet Union.

Unfortunately, although it had gathered some of the best and most self-sacrificing militants of the German labour movement, in its struggle against the right-wing of Social Democracy it had bent the stick too far in the other direction and was born with a significant section of its leadership suffering from an “infantile disorder”, as Lenin phrased it, i.e. the sickness of ultra-leftism. This involved the idea of boycotting the trade unions, anti-parliamentarism and premature attempts to seize power, as in the failed March action in 1921. Lenin and Trotsky had to conduct a struggle against this tendency, which came to a head at the 3rd congress of the International.

The ultra-left wing of the party, refusing Lenin’s policy of the United Front, subsequently split away and formed the KAPD (Worker Communist Party of Germany) in April 1921. This ultra-leftism was taken up repeatedly in the debates and resolutions of the congresses of the Communist International.

Italian Communist Party emerges from the left wing of the PSI

Parallel events were taking place in Italy in the immediate post-war years, with intense class struggle culminating in the occupation of the factories in September 1920. This was in effect the Italian revolution and, had the leadership of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) adhered to a genuinely revolutionary position, Italy would have joined Russia in the task of building a world socialist system.

The PSI had been so radicalised by the great events taking place that it actually adhered en bloc to the Third International at its founding congress. Unfortunately, the right wing of the party remained within its ranks, which meant a clarification was necessary. This kind of problem explains why the Comintern at its Second Congress in 1920 adopted the famous “Twenty-one conditions” as a means of guaranteeing the revolutionary essence of the new International, but more on this later.

While formally adhering to the International, the leadership of the PSI, and in particular the PSI leaders of the CGL trade union confederation, betrayed the 1920 movement of the working class. Because of the vacillating position of the party leaders, the moment was lost and the pendulum began to swing in the direction of counter-revolution. The 1920 defeat prepared the objective conditions for the rise of the Fascist party. At the same time, the necessary differentiation between the genuine revolutionary wing and the centrist and reformist currents of the PSI led to the January 1921 split at the Livorno congress, where about one third of the party went on to found the PCd’I, the Communist Party of Italy.

However, whereas in Germany the ultra-lefts split away from the main party, in Italy the party as a whole was led by the ultra-left Bordiga, who had an abstract, purist position on practically every important question, from parliamentary tactics, to the trade union question, and most importantly on the question of the United Front tactic, which he refused to apply in Italy even though it was the official position of the Comintern.

The Communist International spreads across the globe

The events in Germany and Italy were part of a bigger picture. The years that followed the First World War saw revolution sweep the world, with intense class struggle in one country after another. The old organisations of the working class were put to the test as the workers moved in wave after wave of strike action, factory occupations and general strikes. This led to a crisis within the labour movement and as the old leaders attempted to hold the working class within the confines of what was compatible with the continued existence of capitalism, an opposition began to emerge from below.

As we saw in the cases of Germany and Italy, this led to a split in the old parties of the Second International and the formation of Communist Parties in one country after another. In November 1918 the Hungarian Communist Party was formed and in March of the following year the Hungarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed. That glorious chapter of the history of the Hungarian working class was brought to an end by the reactionary White Romanian army marching into Budapest. Had that revolution succeeded, revolutionary Russia would have broken out of its isolation and a mighty impetus would have been imparted to the process of international revolution. [Note: For more on what happened in Hungary read Alan Woods’ ‘The Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919 – The Forgotten Revolution’.]

In France, the Communist Party came into being at the end of 1920. The SFIO, the French section of the Second International, held its 18th congress in Tours in December 1920, where three quarters of the delegates voted to join the Communist International and to transform the party into the Communist Party of France. The right-wing minority refused to adhere and continued with the name of the old SFIO.

The years that followed the First World War saw revolution sweep the world, with intense class struggle in one country after another. This laid the basis for the rise of the Comintern / Image: Thespoondragon

The years that followed the First World War saw revolution sweep the world, with intense class struggle in one country after another. This laid the basis for the rise of the Comintern / Image: Thespoondragon

However, the French party did not take a stance on Lenin’s conditions and this was to become a source of conflict as a layer of opportunists remained within its ranks and further clarification was required. A by-product of the birth of the French Communist Party was later to be the creation of the Vietnamese Communist Party. A young Ho Chi Minh was present at the 1920 Tours congress, making a speech against imperialism and supporting adherence to the Comintern.

In Poland, the Communist Party was created in December 1918 out of a fusion between the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) and the Polish Socialist Party-Lewica (Left). In India, the Communist Party was formed in October 1920. The Chinese Communist Party was founded in 1921 and would become a significant force by the time of the 1926 revolution.

In many countries, the Communist Parties emerged from the old left wing of the Socialist Parties, but that was not always the case. In China, the Communist Party was the first real political organisation of the working class. In Britain, the Communist Party was formed through a merger of several smaller groups, but the Labour Party continued to dominate the labour movement.

Ultra-left tendencies existed within many of the fledgling Communist Parties. The young party in Britain suffered from the same sickness. Among the questions that were hotly debated were what the party’s stance should be on “parliamentarism”, i.e. whether it should adopt an abstentionist position or participate in parliamentary elections, and what attitude it should have towards the Labour Party. The ultra-left position had substantial support in the party, with leaders such as Sylvia Pankhurst and Willy Gallacher coming out against Lenin’s advice.

These questions were debated in the congresses of the Comintern and were also dealt with by Lenin in his masterpiece, Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder. Through debate and patient explanation, Lenin and the leadership of the Comintern won the party to the idea that it should try to work within the Labour Party.

The Comintern was attempting to build far beyond the borders of Europe, not just in Asia but also in the Americas. Brazil saw a wave of class struggle, beginning in June 1917 in the Sao Paulo strikes, developing into a movement of revolutionary dimensions by 1919. The slogan of “full support for the Soviet Republic” could be heard in all the major cities. In this context, the Brazilian Communist Party, PCB, was formed at the end of 1922.

A Latin American Regional Secretariat of the Comintern was later formed, out of which eventually parties would be created in Mexico, Argentina, Chile and other countries. Further north, the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), was established in 1919 after a split that took place in the Socialist Party of America in the wake of the Russian Revolution.

Revolutionary optimism combined with a sober approach

The spirit of the 1919 Manifesto permeated the first years of the Comintern. The first two congresses dealt with the wave of revolution that spread across the globe in the immediate aftermath of the First World War. But in the Third Congress, the question of the temporary restabilisation of capitalism and the necessary change in tactics that flowed from it were discussed, and this was to become central to the proceedings of the Fourth Congress.

After the First Congress had been celebrated, Trotsky wrote a text, ‘En Route: Thoughts on the Progress of the Proletarian Revolution’. It was written while he was en route to the Southern front where Denikin, one of the reactionary White generals, had launched his offensive in May-August 1919. The text exudes confidence in the spread of the revolution: “In our generation, the revolution began in the East. From Russia it passed over into Hungary, from Hungary to Bavaria and, doubtless, it will march westward through Europe.” It seemed that the revolution was spreading into the heart of Germany where the workers were setting up soviet-type structures and Trotsky boldly stated, “…the proletarian revolution after starting in the most backward country of Europe, keeps mounting upwards, rung by rung, toward countries more highly developed economically.”

This was the perspective of both Lenin and Trotsky. They saw the Russian Revolution not as an end in itself but as the spark to an all-European revolution, in fact, to a world revolution. That was why the Communist International had been created, as an instrument of international revolution. However, in spite of their revolutionary optimism, both Lenin and Trotsky understood that the road to a successful seizure of power by the workers in the more advanced capitalist countries would not proceed in a straight line. In the same text quoted above Trotsky points out that, yes, the working class grows stronger as capitalism develops but at the same time capitalism:

“…presupposes a simultaneous growth of the economic and political might of the big bourgeoisie. It not only accumulates colossal riches but also concentrates in its hands the state apparatus of administration, which it subordinates to its aims. With an ever-perfected art it accomplishes its aims through ruthless cruelty alternating with democratic opportunism. Imperialist capitalism is able to utilise more proficiently the forms of democracy in proportion as the economic dependence of petty-bourgeois layers of the population upon big capital becomes more cruel and insurmountable. From this economic dependence the bourgeoisie is able, by means of universal suffrage, to derive – political dependence.”

He warns against “a mechanical conception of the social revolution”, explaining that both the capitalist class and the working class “gain in strength simultaneously.” And it is this contradiction that explains the need for the Communists not to see the socialist revolution as one triumphant march of the proletariat without understanding the need for the Communist parties to work to win over the majority of the working class with the correct tactics, strategy and programme.

Cleansing the International of false friends

In some countries, the Communist Parties came into being as mass forces splitting away from the old Social Democracy. In the process, the new International found within its ranks opportunist, reformist elements. The new International was in danger of being tainted with the same old treacherous leaders who had betrayed the workers, and it was therefore an urgent task to remove these elements.

The new International had come into being to offer a revolutionary alternative to the decaying corpse of the Second International. To achieve this, it had to be made crystal clear that the Communists would not tolerate class compromise in any form within its ranks. That is why the “Twenty-one conditions” were drawn up and adopted by the Second Congress.

In July 1920, Trotsky wrote a short piece, available here in this volume, under the title ‘On the Coming Congress of the Comintern’ in which he states very clearly that:

“An international organisation of struggle for the proletarian dictatorship can be created only on one condition, namely, that the ranks of the Communist International are made accessible only to those collective bodies which are permeated with a genuine spirit of proletarian revolt against bourgeois rule; and which therefore are themselves interested in seeing to it that in their own midst as well as among other collaborating political and trade union bodies there is no room left not only for turncoats and traitors, but also for spineless skeptics, eternally vacillating elements, sowers of panic and of ideological confusion. This cannot be attained without a constant and stubborn purging from our ranks of false ideas, false methods of action, and their bearers.

“This is exactly the object of those conditions which the Third International has presented and will continue to present to every organisation entering its ranks.”

Lenin originally presented 19 points – which would become 21 in the course of the debate – to establish the basic outlines of a centralised and disciplined revolutionary communist international organisation. Without going into each point in detail, we can list here the basic outlines.

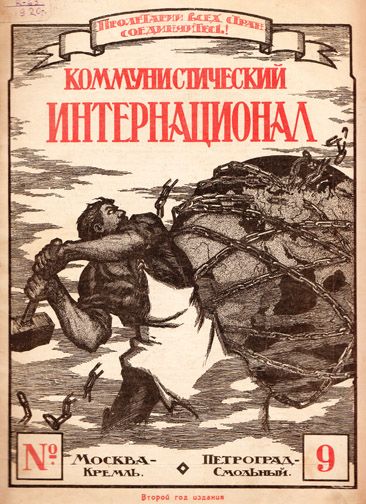

Lenin originally presented 19 points – which would become 21 – to establish the basic outlines of a centralised and disciplined revolutionary communist international organisation / Image: Geograph

Lenin originally presented 19 points – which would become 21 – to establish the basic outlines of a centralised and disciplined revolutionary communist international organisation / Image: Geograph

The publications of the Communist Parties were to be under the control of the elected leaderships. Reformists and centrists were to be removed from all leading positions of the parties in the trade unions, in the parties’ parliamentary representations, in the editorial boards and so on, and replaced with tested communists. There was to be no trust in bourgeois legality, and, where conditions required it, illegal work was to be combined with legal possibilities. There was to be no trust in international courts of arbitration or bodies such as the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations Organisation.

Everywhere the Communist Parties were called on to break completely with all forms of reformism, with the expulsion of the reformist wing from the sections of the International, with specific mention of some of the more famous figures such as Turati in Italy. To strengthen this idea further, another point was added that emphasised the need to regularly purge the party of petit-bourgeois elements.

The Communist Parties were called on to form cells inside the trade unions. These cells were to be under strict party control. The same applied to the parties’ public representatives, such as their MPs. Democratic centralism was the method of running the sections of the International, where internal democratic debate was guaranteed, but once such debate had taken place, decisions would be taken by a vote and this would then apply to the whole party. This was something the opportunist elements particularly objected to as it took away their freedom to say one thing inside the party and then act against those decisions outside in the wider labour movement. It was also ratified that the Communist International was not a federation of national parties, but one world party, with a common discipline, a common programme and policy that applied to all its sections, while taking into account the different local conditions faced by each section.

And finally, in order to send a clear message to all those who adhered to the Comintern, it was made clear in point 21 that anyone who fundamentally rejected the Conditions and Theses agreed by the Communist International was to be expelled.

The adoption of the 21 conditions drew a clear line of demarcation between the revolutionary wing of the international labour movement and all the other tendencies that had fallen under the pressure of capitalist society and had adapted to it. The Communist International was not to be a debating club where resolutions were adopted and then very quickly ignored, as had become the custom with the Second International. And it was not to be a federation of national groups but one world party, following one united policy and one common discipline. It was a fighting organisation created to carry out world socialist revolution, and it was necessary to make this abundantly clear to the workers of the world.

Arguing patiently against ultra-leftism

The birth of the new International, with several sections being mass parties of the working class, was an immense step forward for the genuine forces of revolutionary Marxism, of Bolshevism. However, the coming into being of the new international organisation was only one, albeit important, step towards the final goal of achieving world socialism. The Bolshevik Party had been put to the test by major events over a period of two decades. The party had debated many issues, had drawn important conclusions about tactical and programmatic questions.

The new parties that adhered to the Communist International, however, came without that experience. In many cases, they had only recently broken with the reformists in the Second International, in some cases having witnessed terrible betrayals of the working class at the hands of the Social Democrats. With this came a healthy rejection of the opportunism of the reformists. But there was another side to this, as we have seen, an infantile ultra-leftism and the tendency to simplify the tasks posed by history. As Lenin pointed out, now these new parties had to show that they had the necessary understanding to win the masses and lead them in successful revolution.

Lenin and Trotsky had to contend with sectarian Left Communists like Herman Gorter, who was of the opinion that Communist parties shouldn’t participate in parliamentary activity or trade unions / Image: public domain

Lenin and Trotsky had to contend with sectarian Left Communists like Herman Gorter, who was of the opinion that Communist parties shouldn’t participate in parliamentary activity or trade unions / Image: public domain

We have seen how the question of ultra-leftism affected the young International. The thinking behind this ultra-leftism affected also the approach of many leaders of the Communist Parties towards such matters as what tactics to adopt towards the trade unions, how to win the mass of workers who still looked to the reformists, what position they should adopt on the rights of national minorities and many other questions.

The idea of the onward march to revolution without any need to discuss such matters, as we have seen, was expressed by the ultra-left wing that emerged within the new International. One of the main characteristics of the ultra-lefts is the idea that all that is needed to build a mass revolutionary party is to declare its existence and wait for events to unfold. They do not approach the working class as it actually is, but create an imaginary working class that fits their own preconceived views. The ultra-left does not pose himself or herself the problem of starting from the real level the working class has achieved, from the actual, living working class as it emerges from historical events. A feature of this mode of thinking is to ignore the fact that the working class is composed of different layers, moving at different speeds in the development of consciousness.

The sectarian spends his time talking about the “vanguard”, but has no idea of how such a vanguard can win over the masses that are still under the influence of the reformist tendencies within the labour movement. The Communist International had to deal with this phenomenon within its own ranks. For the ultra-lefts, there was no need to debate tactical issues such as the “United Front” policy as advocated by Lenin and Trotsky.

One of the more prominent Left Communists was Herman Gorter, a Dutch Communist, who was of the opinion that Lenin in his Left-wing Communism, Infantile Disorder did not understand the conditions in the Western countries, that things there were different. He rejected the idea that the Communist parties should participate in parliamentary activity, and called for a repudiation of the trade unions as mere tools of class compromise. For Gorter things were very simple: propagandise the ideas of socialist revolution and “raise consciousness”. If anyone wants to see how Gorter argued his case, see his 1921 ‘Open Letter to Comrade Lenin’. Trotsky replied to Gorter:

“What does Comrade Gorter propose? What does he want? Propaganda! This is the gist of his entire method. Revolution, says Comrade Gorter, is contingent neither upon privations nor economic conditions, but upon mass consciousness; while mass consciousness is, in turn, shaped by propaganda. Propaganda is here taken in a purely idealistic manner, very much akin to the concept of the eighteenth-century school of enlightenment and rationalism. If the revolution is not contingent upon the living conditions of the masses, or much less so upon these conditions than upon propaganda, then why haven’t you made the revolution in Holland? What you now want to do amounts essentially to replacing the dynamic development of the International by methods of individual recruitment of workers through propaganda. You want some sort of simon-pure International of the elect and select, but precisely your own Dutch experience should have prompted you to realise that such an approach leads to the eruption of sharpest divergences of opinion within the most select organisation.” (Leon Trotsky, On the Policy of the KAPD, Speech Delivered at the Session of the ECCI, November 24, 1920)

In his report to the Second Congress, Lenin firmly but patiently explained that, although a revolutionary crisis existed, it was still possible for capitalism to recover and thus avoid revolution. He was intervening against the ultra-left tendency that saw the collapse of capitalism as almost an automatic and inevitable process. He explained that it depended on the revolutionary party and its ability to put itself at the head of the masses:

“…revolutionaries sometimes try to prove that the crisis is absolutely insoluble. This is a mistake. There is no such thing as an absolutely hopeless situation. The bourgeoisie are behaving like barefaced plunderers who have lost their heads; they are committing folly after folly, thus aggravating the situation and hastening their doom. All that is true. But nobody can ‘prove’ that it is absolutely impossible for them to pacify a minority of the exploited with some petty concessions, and suppress some movement or uprising of some section of the oppressed and exploited. To try to ‘prove’ in advance that there is ‘absolutely’ no way out of the situation would be sheer pedantry, or playing with concepts and catchwords. Practice alone can serve as real ‘proof’ in this and similar questions. All over the world, the bourgeois system is experiencing a tremendous revolutionary crisis. The revolutionary parties must now ‘prove’ in practice that they have sufficient understanding and organisation, contact with the exploited masses, and determination and skill to utilise this crisis for a successful, a victorious revolution.”

And he continued, “It is mainly to prepare this ‘proof’ that we have gathered at this Congress of the Communist International.” (V. I. Lenin, The Second Congress Of The Communist International, July 19-August 7, 1920)

How to win the masses: the United Front tactic

The question of how to win the masses was to be posed very sharply at the Third Congress. It is a question that was debated many times during the congresses of the Communist International, but by 1921, the question assumed even-greater importance, as the wave of revolution in Europe was receding. The communist parties had proved too inexperienced, or too weak, to lead the working class in Germany, Hungary and Italy.

The debate was fundamentally between the ultra-lefts and the leadership of the International – with both Lenin and Trotsky taking a leading role – on the question of tactics, in particular on whether the United Front was a correct method of winning the masses to the banner of socialist revolution.

The Bolsheviks had successfully applied the tactic of the United Front in 1917. It is a method whereby the revolutionary party offers united action to the other mass organisations of the labour movement. The communists could not simply ignore the fact that the majority of the working class were still following the lead of the reformists within the movement. The question was posed as to how to break those masses away from the influence of the reformist leaders.

In Russia in 1917 when the masses still had illusions in the reformists – the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries – the Bolsheviks avoided sectarian isolation by posing demands on the other parties of the left in order to connect with the masses following them. On the Provisional Government, for instance, they raised the slogan of “Down with the ten capitalist ministers”, which was an appeal to the reformists who were participating in the government to break with the bourgeois parties. The slogan “All power to the Soviets”, also was not an ultra-left demand, as the Soviets at that time were dominated by the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. In both cases, they were slogans that invited the reformists to take the power.

Lenin understood that, by posing the question in that manner, the revolutionary party could enter into a dialogue with the masses. By placing demands on their leaders, these would be put in the position of either refusing the offer of unity and exposing themselves in the eyes of the masses as obstacles to working class unity, or they would have to accept joint action, which meant participating in mass struggles where the revolutionaries would prove their superiority in ideas and methods. It was in this way that the Bolsheviks successfully won the majority of the working class and prepared the conditions for a victorious revolution.

At the Third Congress much of the polemic centred around the question of the famous “Open Letter” of the Central Committee of the United Communist Party of Germany to all workers, trade unions and socialist organisations to unite their forces against reaction and the bosses’ offensive. The reformist leaders rejected joint action with the Communists, even though at rank-and-file level it was clear the workers desired unity.

Lenin supported the tactic elaborated around the Open Letter, but the leaders of several Communist parties considered this method as one of unacceptable compromise. An example of this kind of leadership was that of the Italian Communist Party, who resisted the idea that they should offer a united front to the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) against the Fascists. Their sectarian stance served to further isolate and weaken the Italian Communist Party and divide the Italian working class as the capitalists mobilised the Fascists to crush the workers’ movement. Terracini, a delegate of the Italian Communist Party, called on the congress to renounce such methods, and supported the KAPD delegate Hempel, a Left Communist, who had stated: “The Open Letter is opportunist, it cannot be remedied.” Lenin responded: “The Open Letter is exemplary as the opening act of the practical method to effectively win over the majority of the working class.”

The German Communists unfortunately revealed their lack of experience during the March Action in 1921 when they attempted a premature uprising, not having prepared the ground beforehand. In particular, they had not done the necessary preparatory work of winning the social-democratic workers nationally. Having made an ultra-left mistake in 1921, however, they would later make the opposite mistake of not recognising the revolutionary possibilities that emerged in 1923.

In the ‘Guidelines on the Organisational Structure of Communist Parties, on the Methods and Content of their Work’ adopted at the Third Congress, we find a manual for how Communists should work within the labour movement. It is worth noting the following passage:

“In the struggle against the social-democratic and other petty-bourgeois leaders of the trade unions and various workers parties, there can be no hope of obtaining anything by persuading them. The struggle against them must be organised with the utmost energy. However, the only sure and successful way to combat them is to split away their supporters by convincing the workers that their social-traitor leaders are lackeys of capitalism. Therefore, where possible these leaders must first be put into situations in which they are forced to unmask themselves; after such preparation they can then be attacked in the sharpest way.”

The Guidelines were aimed at educating the still young and inexperienced Communist parties. They still had much to learn, as Lenin commented in ‘A Letter to the German Communists,’ written shortly after the Third Congress on 14 August, 1921:

“At the Third Congress it was necessary to start practical, constructive work, to determine concretely, taking account of the practical experience of the communist struggle already begun, exactly what the line of further activity should be in respect of tactics and of organisation. We have taken this third step. We have an army of Communists all over the world. It is still poorly trained and poorly organised. It would be extremely harmful to forget this truth or be afraid of admitting it. Submitting ourselves to a most careful and rigorous test, and studying the experience of our own movement, we must train this army efficiently; we must organise it properly, and test it in all sorts of manoeuvres, all sorts of battles, in attack and in retreat. We cannot win without this long and hard schooling…

“In the overwhelming majority of countries, our parties are still very far from being what real Communist Parties should be; they are far from being real vanguards of the genuinely revolutionary and only revolutionary class, with every single member taking part in the struggle, in the movement, in the everyday life of the masses. But we are aware of this defect, we brought it out most strikingly in the Third Congress resolution on the work of the Party.”

It was not a foregone conclusion that the tactic of the United Front would be adopted by the Communist International. Lenin and Trotsky actually started out as being in a minority on this question, and were in fact considered the “right wing” by many of the delegates. The leadership had to argue its case, and it was only through democratic debate, and with the power of their arguments, that in the course of the congress Lenin and Trotsky won over the majority of the delegates. This fact serves to highlight the democratic nature of the Communist International. Different opinions were expressed openly without fear of being ostracised or expelled, as was to become the norm in later years under the Stalinist regime.

It was necessary to draw a balance sheet of the immediate postwar years. By 1922, the revolutionary wave had peaked and had begun to recede. The workers in one country after another had moved in a revolutionary direction, but had failed to take power. The capitalist class had managed to survive the wave of revolution and they prepared a counteroffensive. The clearest example of this was to be Italy in October of that year, when Mussolini came to power and began the process of consolidating his position in preparation for an open dictatorship, where all the organisations of the working class would be destroyed.

A serious reappraisal on the part of the Communist International involved stepping up the struggle against the left-wing Communists in the International who believed that there was no need to discuss tactics such as the United Front. That explains the content of the ‘Theses on Comintern Tactics’ voted on at the Fourth Congress. The Theses, in acknowledging the new situation, stated:

“Since nowhere, except in Russia, did the proletariat deal capitalism a decisive blow while it was weakened from the war, the bourgeoisie, with the help of the social democrats, was able to defeat the militant revolutionary workers, re-establish its political and economic power and launch a new offensive against the proletariat. All the efforts of the bourgeoisie to get the international production and distribution of goods running smoothly again after the upheavals of the war have been made solely at the expense of the working class.

“The systematically organised international capitalist offensive against all the gains of the working class has swept across the world like a whirlwind. Everywhere reorganised capital is mercilessly lowering the real wages of the workers, lengthening the working day, curtailing the modest rights of the working class on the shop floor and, in countries with a devalued currency, forcing destitute workers to pay for the economic disasters caused by the depreciation of money etc.”

Although it was a new phenomenon and still in its early stages of development, Fascism was beginning to emerge in several countries, as the theses noted:

“Closely linked to the economic offensive of capital is the political offensive of the bourgeoisie against the proletariat. Its sharpest expression is international fascism. Since falling living standards are now affecting the middle classes, including the civil service, the ruling class is no longer certain that it can rely on the bureaucracy to act as its tool. Instead, it is resorting everywhere to the creation of special White Guards, which are particularly directed against all the revolutionary efforts of the proletariat and are being increasingly used for the forcible suppression of any attempt by the working class to improve its position.”

In the face of this generalised onslaught of the capitalist class, it was necessary to unite the forces of the working class. If the Communist Parties applied the correct tactics they would be able to increase their influence within the labour movement and win more and more layers of the workers to the banner of revolutionary Communism. As the Theses explained:

“There is consequently an obvious need for the united front tactic. The slogan of the Third Congress, ‘To the masses’, is now more relevant than ever. The struggle to establish a proletarian united front in a whole series of countries is only just beginning. And only now have we begun to overcome all the difficulties associated with this tactic. The best example is France, where the course of events has won over even those who not so long ago had opposed this tactic on principle. The Communist International requires that all Communist Parties and groups adhere strictly to the united front tactic, because in the present period it is the only way of guiding Communists in the right direction, towards winning the majority of workers.”

On such a crucial question as the United Front tactic, however, the ultra-lefts did not budge. When they did make some concessions, it was along the lines that a united front “from below” was permissible, but not “from above”. By this, they meant that no dialogue with the reformist leaders was admissible. This was infantile to the extreme. The workers “below” still looked to the reformist leaders “above” and therefore to pose demands on these leaders was a way of entering into dialogue with the masses, but the ultra-lefts refused to listen.

The case of Bordiga, the leader of the Italian party, provides an example of this stubbornness. In the face of advancing Fascism, he refused to accept that a United Front tactic was necessary to unite the workers against the fascist squads. His ultra-leftism contributed to the division and weakening of the working class. In reply to this infantilism, the Theses were very clear:

“The main aim of the united front tactic is to unify the working masses through agitation and organisation. The real success of the united front tactic depends on a movement ‘from below’, from the rank-and-file of the working masses. Nevertheless, there are circumstances in which Communists must not refuse to have talks with the leaders of the hostile workers’ parties, providing the masses are always kept fully informed of the course of these talks. During negotiations with these leaders the independence of the Communist Party and its agitation must not be circumscribed.”

The objective situation internationally demanded the immediate and urgent implementation of a correct tactic on the part of the Communist parties. So important was the carrying out of the United Front for the Communist International, that in the final section of the Theses it states categorically:

“Now, more than ever, the strictest international discipline is necessary, both within the Communist International and in each of its separate sections, in order to carry out the united front tactic at the international level and in each individual country.

“The Fourth Congress categorically demands that all sections and all members keep strictly to this tactic, which will bring results only if it is unanimously and systematically carried out not only in word but also in deed.”

“Acceptance of the twenty-one conditions involves carrying out all the tactical decisions taken by World Congresses and by the Executive Committee, the organ of the Communist International between World Congresses. Congress instructs the Executive Committee to be extremely firm in demanding and seeing that every Party puts these tactical decisions into practice. Only the clearly defined revolutionary tactics of the Communist International will ensure the earliest possible victory of the international proletarian revolution.”

The ‘Theses On The United Front’ adopted by the EC of the Communist International in December 1922 laid down in detail how the tactic of the united front should be applied in each country, depending on the local conditions. In France, the majority of the advanced layers of the working class had already joined the Communist Party, nonetheless the United Front tactic was still a necessary means of winning over the majority of the working class. This was later to be confirmed by events in the late 1920s, which saw the mass of workers look to the SFIO, in spite of it being a small minority at the Tours congress. Unfortunately, by then the Communist International had adopted the ultra-left theory of the “Third Period”, which involved abandoning the United Front tactic and declaring the social-democrats as “social fascists”, ignoring all the precious lessons of the first four congresses. [Note: See Trotsky’s 1929 text ‘The ‘Third Period’ of the Comintern’s Mistakes‘ for more on this]

In Britain, where the Communist Party was a much smaller force, the question could not be posed in the same way as in Germany where the Communist Party was a mass party. The advice Lenin gave the British Communists in his class ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: an Infantile Disorder’, is repeated in the Theses:

“The British Communists must launch a vigorous campaign for their admittance to the Labour Party. The recent sell-outs by the trade-union leaders during the miners’ strike etc., the steady capitalist pressure on the workers’ wages etc., all this has roused a deep discontent among the masses of the British proletariat, which is becoming more revolutionary. The British Communists must do their utmost, whatever the cost, to extend their influence to the rank-and-file of the working masses, using the slogan of a united revolutionary front against the capitalists.”

Fighting to transform the trade unions

The Comintern sought to organise the struggle to remove the opportunist leaders of the trade unions and turn these organisations into fighting organs of the working class / Image: public domain

The Comintern sought to organise the struggle to remove the opportunist leaders of the trade unions and turn these organisations into fighting organs of the working class / Image: public domain

The approach Communists should have towards the trade unions was also a question of debate which followed more or less similar lines to the discussions on the united front. The trade unions were created by the working class as a means of both defending workers against the attacks of the bosses and of fighting for improved conditions and wages. However, they also had the tendency to become bureaucratised, and from being a weapon in the hands of the workers they could become instruments which the bosses, through the union leaders, used to hold back the working class from taking revolutionary action in key moments of the class struggle. The trade union leaders had also played an important role in the process of degeneration of the parties of the Second International, generally supporting the right wing of the socialist and social-democratic parties.

Therefore the question was posed: do we leave the old unions and set up independent militant unions or do we work to transform the unions from within? The ‘Theses on the Trade Union Movement, Factory Committees and the Third International’ were adopted during the second congress, and they remain as relevant today as when they were first debated, and they were very clear. They acknowledged the following:

“…the trades unions proved to be in most cases, during the war, a part of the military apparatus of the bourgeoisie, helping the latter to exploit the working class as much as possible in a more energetic struggle for profits. Containing chiefly the skilled workmen, better paid, limited by their craft narrowmindedness, fettered by a bureaucratic apparatus disconnected from the masses, demoralised by their opportunist leaders, the unions betrayed not only the cause of the social revolution, but even also the struggle for the improvement of the conditions of life of the workmen organised by them. They started from the point of view of the trade union struggle against the employers, and replaced it by the programme of an amicable arrangement with the capitalists at any cost.”

A more damning condemnation of the trade unions would be difficult to find. And yet, the Communist International did not draw the conclusion that the Communist workers should break with these unions. On the contrary, they understood that, while the unions tended to become bureaucratised, they also remained rooted in the working class and were thus prone to come under the pressure of the working class as it began to mobilise. Across Europe there was a mass influx into the trade unions, as the workers sought an organisation to defend themselves in the conditions of crisis that emerged at the end of the First World War.

Millions of previously unorganised workers were flowing into the trade unions. In Britain, trade union membership went from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million by 1918, and in the immediate post-war years reaching 8.3 million by 1920. In Italy, the CGL from its 250,000 members at the end of the war, had ballooned to 2,150,000. In France, the CGT, from its 355,000 members in 1914 grew to 600,000 by 1918 and then peaked to 2,000,000 in 1920. In Germany, membership of socialist-led trade unions rose from 1,665,000 in 1918 to 5,479,000 in 1919.

Trotsky, in one of the texts in this volume (French Socialism on the Eve of Revolution) comments on this process, answering the reformist interpretation of what was happening:

“The great influx of workers into the trade unions is elicited not by petty, day-to-day questions, but by the colossal fact of the World War. The working masses, not only the top layers but the lowest depths as well, are roused and alarmed by the greatest historical upheaval. Each individual proletarian has sensed to a never equalled degree his helplessness in the face of the mighty imperialist machine. The urge to establish ties, the urge to unification and consolidation of forces has manifested itself with unprecedented power.”

The Theses noted that:

“…the wider masses of workers, who until now have stood apart from the labour unions, are now flowing into their ranks in a powerful stream. In all capitalist countries a tremendous increase of the trades unions is to be noticed, which now become organisations of the chief masses of the proletariat, not only of its advanced elements. Flowing into the unions, these masses strive to make them their weapons of battle. The sharpening of class antagonism compels the trades unions to lead strikes, which flow in a broad wave over the entire capitalist world, constantly interrupting the process of capitalist production and exchange. Increasing their demands in proportion to the rising prices and their own exhaustion, the working classes undermine the bases of all capitalist calculations and the elementary premise of every well-organised economic management. The unions, which during the war had been organs of compulsion over the working masses, become in this way organs for the annihilation of capitalism.”

The ultra-left response to the bureaucratic degeneration of the old trade unions was to work towards splitting them and setting up new more militant organisations. In some cases, splits did take place and this was a question the Communists needed to deal with. The leadership of the Communist International understood that splitting away the most militant sections of the working class from the mass would be a serious mistake. The Theses state clearly that:

“Bearing in mind the rush of the enormous working masses into the trades unions, and also the objective revolutionary character of the economic struggle which those masses are carrying on in spite of the trade union bureaucracy, the Communists must join such unions in all countries, in order to make of them efficient organs of the struggle for the suppression of capitalism and for Communism. They must initiate the forming of trades unions where these do not exist. All voluntary withdrawals from the industrial movement, every artificial attempt to organise special unions, without being compelled thereto by exceptional acts of violence on the part of the trade union bureaucracy such as the expulsion of separate revolutionary local branches of the unions by the opportunist officials, or by their narrow-minded aristocratic policy, which prohibits the unskilled workers from entering into the organisation – represents a great danger to the Communist movement. It threatens to hand over the most advanced, the most conscious workers to the opportunist leaders, playing into the hands of the bourgeoisie.” [Our emphasis]

Only by applying this policy towards the trade unions would it be possible for the Communists to organise the struggle to remove the opportunist leaders and turn these organisations into fighting organs of the working class. The ultra-lefts did not understand that to win the mass of workers who still had illusions in the reformist trade union leaders, it was not enough to simply declare new, more militant, trade unions.

As we can see, the problem of how to transform the unions is not a new one. It appears again and again throughout the history of the labour movement. The bureaucratic degeneration of the unions poses the question before revolutionaries as what to do: stay and fight, or leave and set up new unions? This debate has been had many times in many countries for more than a century now and there is nothing new to invent here. All the various theses on the trade union question adopted by the Comintern in its first four congresses provide the answers.

In periods of relative calm on the industrial front, when the mass of workers are not organised, and when capitalist upswing allows for some concessions to be made to the workers, a bureaucratic caste can occupy leading positions, and when the crisis of capitalism impels the masses to struggle, this can become an obstacle. The Communist International understood that a way of strengthening the rank and file trade unionists against the bureaucracy was to lean on the mass of workers at rank and file level. One important way of doing this was by building factory committees directly in the workplaces:

“Where within the trades unions or outside of them organisations are formed in the factories, such as shop stewards, factory committees, etc., for the purpose of fighting against the counter-revolutionary tendencies of the trade union bureaucracy, to support the spontaneous direct action of the proletariat, there, of course, the Communists must with all their energy give assistance to these organisations.”

The advantage of such committees is that they involve all the workers and not just those who are members of a trade union. They are genuine expressions of workers’ democracy at rank-and-file level, and they come into being as workers attempt to impose workers’ control in the workplaces. They can also be used as levers not only to resist the encroachments of the trade union bureaucracy, but also as tools in the battle to bring the unions back under the control of the workers. But the most important aspect of the building of the factory committees by the Communists is that they prepare the ground for revolution and the taking of power by the working class.

The Trade Union question at the Third Congress

The following year in July 1921 the Communist International returned to this key question for Communists. They tackled the idea promoted by the bosses of so-called “trade union neutrality”, i.e. that the trade unions should have no party affiliations.

The capitalists understood that it was not possible to convince the trade unions to adhere to the parties of the bosses and therefore they attempted to convince them not to adhere to any party. This was an idea that had the clear aim of holding back the working class from reaching the necessary conclusion that capitalism could not be reformed but had to be overthrown, which would have led them directly to the Communist parties.

The trade union theses voted at the Third Congress, ‘The Communist International and the Red International of Trade Unions – The Struggle Against the Amsterdam (scab) Trade-Union International’ opened with the following paragraph:

“The bourgeoisie keeps the working class enslaved not only by means of naked force, but also by subtle deception. In the hands of the bourgeoisie, the school, the church, parliament, art, literature, the daily press – all become powerful means of duping the working masses and spreading the ideas of the bourgeoisie into the proletarian milieu.”

The Theses also explain that:

“In order to maintain its rule and squeeze surplus value from the workers, the bourgeoisie needs not only the priest, the policeman, the general and the informer, but also the trade-union bureaucrat and the kind of ‘workers” leader that teaches trade-unionists the virtues of neutrality and non-participation in political struggle.”

Up until then, the capitalists had, in fact, successfully included the trade union bureaucracy in their arsenal of weapons for diverting the class struggle, but now that millions upon millions of workers had joined the unions, there was the risk that, in the course of struggle, these organisations would free themselves of bourgeois influence:

“Hence the frantic efforts of the international bourgeoisie and its social-democratic hangers-on to maintain, at all costs, the hold of bourgeois social democratic ideology over the trade unions.”

By 1921, the revolutionary wave that had followed the end of the First World War had begun to recede. In France, a militant railway workers’ strike – followed by a badly organised general strike – went down to defeat. In Italy, the working class had suffered the defeat of the occupied factories movement in 1920 and in the aftermath, trade union membership started to decline sharply. A similar picture could be seen across Europe. After the mass influx of the period 1918-20, a period of rolling back of the membership began. In some countries, this situation provoked splits in the unions.

The Communist International took note of this, and in its 1921 theses stated the following:

“Communists must explain to the proletariat that their problems can be answered not by leaving the old trade unions for new ones, or by staying outside the unions, but by revolutionising the trade unions, ridding them of reformist influence and the treacherous reformist leaders, and transforming them into a genuine stronghold of the revolutionary proletariat.

“The principal task of all Communists over the next period, is to wage a firm and vigorous struggle to win the majority of the workers organised in the trade unions. The Communist must not be discouraged by the present reactionary mood of the labour unions, but must try to overcome all resistance and by actively participating in their day-to-day struggle, win the unions to Communism.”

How many times have we seen militant rank-and-file trade unionists being discouraged by reactionary moods inside the trade unions? It is a phenomenon that repeats itself over and over again. It comes from a lack of understanding of the ups and downs of the trade union movement, which comes from the lack of a Marxist perspective on history. When movements go down to defeat, pessimistic moods can grip the mass of workers and the wrong conclusions can be drawn.

The general principle was that Communists stay and organise within the existing trade unions. However, the Comintern also understood that such a policy was not always possible to apply and therefore it had a flexible approach. In situations where remaining within the unions involved abandoning revolutionary work within them, splits could become inevitable. Even then, however, “The Communists, in case a necessity for a split arises, must continuously and attentively discuss the question as to whether such a split might not lead to their isolation from the working masses.”

In spite of all the best advice, sometimes tensions reach a point where splits in the unions become inevitable. In such circumstances, it would be the height of formalism to insist on staying in the old bureaucratised unions. The Theses deal with such situations where the more militant wing among the trade unionists has already split from the old unions. In such circumstances, “…the Communists are bound to support such revolutionary unions…”

The position of the Communist International towards those trade unionists and trade union organisations outside the mass established unions can be seen in its approach to this question in the United States. In noting that, “The same revolutionary process is occurring in America, though more slowly,” the Theses stress that:

“Communists must on no account leave the ranks of the reactionary Federation of Labour [composed in the main of skilled workers]. On the contrary, they should seek to gain a foothold in the old trade unions with the aim of revolutionising them. It is vital that they work with the IWW members most sympathetic to the Party; this does not, however, preclude arguing against the IWW’s political positions.”

Thus the advice of the Communist International was to be friendly and even work with groups that had broken from the official mass trade unions, such as the AFL in the United States, while attempting to turn them towards the mass ranks within those same unions. Thus, even when it was necessary to support minority militant unions outside the old established unions, it was necessary to always keep in mind that the task was still to win the masses that remained within the official unions.

At the Third Congress, the Communist International also adopted as part of the trade union Theses a ‘Programme of Action’. In this programme, we find what are fundamentally transitional demands, which later would become key programmatic points in The Transitional Programme drawn up by Trotsky in 1938 as the founding document of the Fourth International.

In the ‘Programme of Action’ we find demands such as the elections of factory committees, maintenance money to be paid by the bosses to workers losing their jobs, the reduction of the working day, the call to open the books so that the workers can investigate the reasons behind factory closures, the introduction of workers’ control, the election of factory committees, the occupation of the factories and the formation of self-defence groups when the situation demands them.

The programme was developed in contrast to the class compromise proposed by the official trade union leaders, who were always looking for means of blunting the class struggle. One example was that of “profit-sharing”, an idea which has not gone away to this day. As the Theses explain, “Profit-sharing means that workers receive an insignificant part of the surplus value they produce, and the idea should therefore be subjected to harsh and rigorous criticism. ‘Not profit-sharing, but an end to capitalist profit’ should be the slogan of the revolutionary unions.”

The trade union Theses adopted at the Second and Third Congresses of the Communist International are in fact a treasure trove of ideas on how Marxists should work in the unions, with what approach and with which programme, and should be studied thoroughly today. Many times over the past one hundred years we have seen serious mistakes being made in this field of work and they could have been avoided had several generations of militants been educated in the ideas and principles elaborated on the trade unions during the first four congresses of the Comintern.

The National and Colonial Questions

Another key question debated in the congresses of the Communist International was the National Question. In 1914, Lenin had published his seminal work, ‘The Right of Nations to Self-Determination’. The ideas elaborated by Lenin on this key question would become translated into theses and resolutions discussed at the congresses of the Comintern. However, the case had to be argued for through debate. Support for these ideas did not come automatically, as some of the Communist leaders approached the question in a formal and mechanical manner.

Lenin’s position was not understood even by some outstanding revolutionary leaders. One of these was Rosa Luxemburg. In her 1918 text, ‘The Russian Revolution’, she stated: