The general strike of the winter of 1960-61 destroyed in practice all the myths of the ‘bourgeoisified’ working class in Belgium and in Europe. For five weeks, a total of 1 million workers made the bosses and their state tremble. In this article we look back at those dramatic events.

The Belgian general strike in the winter of 1960-61, also known as the ‘strike of the century’, was not just an inter-professional social conflict or a generalised five-week work stoppage. This strike was a volcanic moment, a huge political – sometimes insurrectional – showdown between the working class on the one hand and all the institutions of the capitalist status quo on the other.

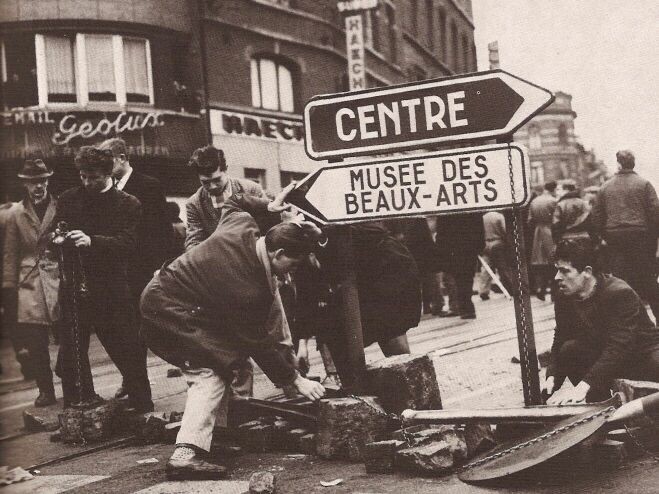

Up to 300 demonstrations, often massive, were registered in the country during this short period of time. 3,750 acts of sabotage were committed, often to prevent strike-breakers from restarting production. It was a genuine workers’ rebellion against the regime. The government, the employers, the state apparatus, the church, the right-wing unions and the other pillars of the system all united against the organised labour movement. In this sense as well, the strike was in line with the tradition of mass direct action by Belgian workers, as initiated in the 19th century.

The historian Alain Meynen stresses the exceptional nature of this strike:

“Previous general strikes were dominated by the acquisition or safeguarding of democratic rights and freedoms (1893, 1902, 1913, 1950) or by immediate social demands (summer 1936: the eight-hour day, paid holidays, etc.). On the other hand, the general strike of 60-61 was the first in the history of the Belgian workers’ movement to aim at structural economic reforms and to lead the class struggle against the capitalist relations of production.”[1]

Power of the working class

The general strike of 1960-1 still haunts the Belgian ruling class to this day, although it was ultimately defeated / Image: public domain

The general strike of 1960-1 still haunts the Belgian ruling class to this day, although it was ultimately defeated / Image: public domain

According to Trotsky, nothing can stop the will of the working class to change society; the 15 years of post-war Belgium bear testament to this. After the abandonment of the “national uprising”[2]prepared by the communist-influenced resistance to the Liberation, the first-ever socialist-communist governments came to power. These governments expressed a majority desire to break with the past of the inter-war period. But soon the communist ministers had to leave the government and the Independence Front, the main organisation of resistance against the German occupier under the decisive influence of the communists, was disarmed.

Reluctant to repeat the political and social turbulence of the 1920s and 1930s, and faced with a powerful and demanding workers’ movement, the most far-sighted elements of the capitalist class felt obliged to make concessions. The introduction of Social Security and other social benefits was supposed to calm down the anti-capitalist fervour of the workers. In return, the socialist and trade union leaders committed themselves to respecting the capitalist system and greatly increasing the productivity of the workers. This led to the famous “Productivity Pact”. But these concessions, while not insignificant, were too little for many workers. Moreover, the catholic and liberal right-wing parties and the bosses – once the fears of the post-war period had been overcome – rebelled and counter-attacked.

A crisis of the regime

This backlash would lead to the first serious crisis of the regime in 1950, in response to the famous Royal Question. The return of King Leopold III as a head of state after the war was (rightly) perceived by the workers as an attempt to return to the pre-war situation. Leopold III had refused to support the Resistance against German occupation. Against the will of the government he accepted the defeat of the Belgian Armed Forces. He had also refused to recognise the government in exile and had paid a personal visit to the Führer in Bergtesgaden at the beginning of the war. The most reactionary forces were behind the campaign for this king who had sympathised with fascism. A militant general strike forced his abdication.

Then there was the School Question in 1958, when the Catholic Church (supported by its influential school network) violently rebelled against the limits placed on its power. In other words, two real crises of the regime had shaken Belgium, starting a slow radicalisation within the working class.

At the same time, the Belgian economic structure was ageing; the economy of the Walloon region, the industrial epicentre of the country, was in decline; and a recession had started in 1958-59. After 1959, the economy began to pick up again. This change in economic conditions and the reduction in unemployment led to growing confidence amongst the workers in their own strength. So it was not so much the recession that triggered the strike of the century, but the long structural crisis of post-war capitalism. The arrogance and short-sightedness of the bourgeoisie would finally lead to a huge social explosion in reaction to the Loi Unique (Unitary Law), a fiscal austerity programme concocted by the Catholic-Liberal government.

Economic feudalism

A journalist from Le Monde remarked at the time that “it is probably necessary to go to Japan, and even pre-war Japan, to find such an (economic) organisation”. He was referring to the obsolete economic infrastructure in Belgium. Georges Staquet, shop steward of the socialist FGTB in the Charleroi steel industry, also expressed it in his own way: “We were still working with 30-tonne transformers”.

The figures don’t lie: from 1957 to 1960, the Belgian economy grew by barely 1.6 percent, compared to 8.8 percent in the rest of Europe! Since 1947, the working population had decreased by 9,000 units. Between 1948 and 1958, 244 companies went bankrupt, not counting the decline of the coal industry that dominated the economy. Leading sectors such as the chemical industry were also in a bad shape: their share of investment in GDP from 1954 to 1958 was only 15.4 percent compared to 17.6 percent in France, 20 percent in Italy and 21.7 percent in West Germany. Public investment was also lagging behind. After a period of real wage increases after the war, from 1948 onwards this increase became lower in Belgium than in neighbouring countries. In 1960, indirect taxes accounted for 60.8 percent of the state’s tax revenue. The largest holding company, Société Générale, managed to evade taxes and recorded a net profit of 510 million Francs.

Moreover, the PSB (Parti Socialiste Belge, the Socialist Party at the time, which was still unified and comprised Flemish and French-speaking socialists) was passively accepting this economic decline and its logic. It was in this context that political and trade union radicalisation manifested itself in the 1950s. At the FGTB congresses of 1954 and 1956 the theses of the national secretary André Renard were very popular. The voluminous brochure ‘Holdings and economic democracy’, with its figures, statistics and analyses, made many workers aware of what they already knew and felt: the Belgian bourgeoisie was an extremely parasitic and conservative class, which could no longer develop society.

“Structural Reforms”

The holding companies held the economy in their grip. A ‘holding company’ is a company whose purpose is to bring together shareholders with a view to acquiring real influence in the companies they hold. For example, the famous Société Générale de Belgique held one third of the country’s economy. 200 families controlled the capitalist economy but proved to be very conservative, at a time when the economy needed to be reorganised and modernised. This led to the programme of famous “structural reforms”, also known as “anti-capitalist structural reforms”, put forward by the socialist union FGTB. They aimed at increasing the national income and distributing it better. The most important elements were: harmonious planning of the economy, nationalisation of the energy sector, control of holding companies and coordination of the credit sector.

The programme of structural reforms was similar to what was presented by the left-wing magazines Links and La Gauche,[3] and in the PSB and the programmes of the international left in France, Great Britain and Italy. Links and La Gauche popularised the “structural reforms” of the PSB and described them as “a step in the direction of socialism”. However, as Jacques Yerna, the former secretary of the FGTB in Liège, said, these structural reforms were “vague and ambiguous”. On the one hand, they were proposals aimed at improving and modernising capitalism, at better managing this system. On the other hand, they were a series of demands – in fact, transitional demands, as Marxism defines them – which called capitalism into question. If these demands had been propagated by the workers’ movement, they could, in connection with the real class struggle, have made large sections of the population aware of the need to transform capitalist society into a socialist society.

The programme of structural reforms and the propaganda in favour of them gave the strike of 1960-1961 an offensive character. André Renard set the objectives of the strike during a rally in Herstal in November 1959:

“We appealed to you. We will do it again and soon. We’re not meeting just to protest against the draft Loi Unique, but to engage in a more definitive struggle against the regime itself. If we obtain the withdrawal of the Unitary Law, this result will have only relative value. Our economy will remain in difficulty. Because if we do not find solutions, real solutions to the problems of the day, there will be no economic prosperity… We cannot invoke a parliamentary majority against the people. We will go as far as we did in 1950. There is no doubt about the unity of the workers. We are committed to the struggle. We will go to the end.”[4]

Fifteen years after the end of the Second World War, the radical changes hoped for had not materialised and the workers – together with some of their leaders – began to look for a scientific programme to change society. Despite the limitations, incompleteness and confusion of the structural reform programme, the most conscious activists in Flanders and Wallonia saw it as an important lever for social change.

Warming up

During the May Day demonstration in 1949 in Verviers, on the eve of the Royal Question, Renard gave this warning: “If we have to declare a general strike, we will not strike against the King but for social purposes. The strike will call into question the regime itself and it will be insurrectionary.” 11 years later, in Liège, Renard repeated this threat: “If within two months the negotiations fail, this country will find itself in a climate of social revolution.”

In the workplaces, the struggle had also become more radical. In 1957, 200,000 metal workers went on strike. Two years later, the docks and the port of Antwerp came to a standstill, 25,000 Ghent textile workers went on strike against unemployment and 150,000 miners stopped working against the closure of their mines. On 29 January 1960, the FGTB called for a 24-hour strike for urgent reforms of economic structures. 30,000 civil servants demonstrated for the right to strike. New strikes broke out against the closure of the collieries in the Borinage.

The “law of misfortune”

On 29 May 1960, the PSB celebrated its 75th anniversary. The event in the centre of Brussels lasted five hours! 150,000 people were present, a dazzling demonstration of strength. On 27 September of the same year, Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens announced the draft Loi Unique, which was officially entitled “Law on Economic Expansion, Social Progress and Financial Recovery”. It is commonly referred to as the “law of misfortune”, because it raised the pension age, raised taxes and cut unemployment benefits. Most newspapers rejected the Loi Unique. The Christian weekly La Relève, which defended the law, had to admit in an editorial that the project “did not imply either precise social progress or concrete economic expansion”.

The PSB rejected the law and voted against it in Parliament. Within the FGTB, the arguments of the right wing echoed the positions of the Christian union ACV/CSC. Louis Major, General Secretary, and Dore Smets of the socialist building workers’ union, argued that there could be no trade union action for political purposes. However, Georges Debunne of the CGSP/ACOD (the Centrale Générale des Services Publics) proposed a general strike of unlimited duration. André Renard defended a motion for a 24-hour strike in January 1961 and a referendum for a general strike. At the FGTB national committee meeting on 16 December 1960, the motion was rejected by 48.5 percent votes against, 46.5 percent in favour.

The big strike

Paradoxically, this vote was the signal for the workers to spontaneously go on strike a few days later. The CGSP (socialist public service union) and the Miners’ Federation were the only ones to officially declare a general strike. The strike started in the public services and rapidly spread to the private sector, both in Flanders and Wallonia.

André Renard became its de facto leader. Louis Major and the trade union right within the FGTB did not want to lead anything, quite the contrary. When the Antwerp dockers also lit the powder keg, Louis Major, who was also a socialist MP, declared before Parliament: “Mr. Prime Minister, we tried by all means, even with the help of the bosses, to limit the strike to one professional sector”. The ACV/CSC did not participate, but in many places the members of the Christian union defected and joined the socialist union. During the first week of the strike, the ACV/CSC leadership was paralysed. Frightened by a possible reaction from its rank and file, it laid low. In the second week, however, it actively organised voluntary workers and strike-breakers, hand in hand with the bosses and the gendarmerie (the national paramilitary police force). The Catholic Church was also getting involved. During his Christmas speech, the head of the Church, Cardinal Van Roey condemned the strike as contrary to “Christian morality”.

During the first weeks of the strike the government was paralysed. At the height of the strike, after two weeks, about a million workers stopped work, from Ostend in the north to Luxembourg in the south. The working class showed where the real power in the country lay. At this point, the Loi Unique was not only a reprehensible law that was being questioned. Objectively speaking, a state of dual power had emerged in society. The government and the bourgeoisie had lost control of the situation. The economy could not restart without the consent of the strikers.

Dual power

Dual power is not sustainable, it must fall in favour of one side or the other / Image: La Wallonie

Dual power is not sustainable, it must fall in favour of one side or the other / Image: La Wallonie

The question of who is in power is posed in very concrete terms during a general strike. In many places in Wallonia, strike committees organised transport and regulated social life. No car, motorbike or lorry could circulate without the authorisation of the union. The Borinage was surrounded by barricades and access to it had become impossible. From the beginning, the government organised a forceful deployment of the gendarmerie (18,000 men) to protect the “vital places”, dismantle the picket lines and “protect” the scabs. In addition to the action of the gendarmerie, the army mobilised 12,000 to 15,000 men to guard the industrial infrastructure, the viaducts, the post office, the telegraph, etc. The state also started the requisitioning of strikers. During clashes between workers and gendarmes, four demonstrators lost their lives.

A state of dual power is also a state of double impotence. Two powers face each other: on the one hand the working class which has put a stop to production, transport, trade, public services; on the other, the big state institutions, the employers, the Church, the government and the forces of repression (the gendarmerie and the army), which are certainly still in place but which have lost control of the situation. This is an unparalleled political impasse, which cannot last forever. At this point, workers’ leaders, political and trade union organisations and their programmes are being put to the test.

Dual power must sooner or later shift in favour of one side or the other. Either the workers and their families, as well as the lower middle classes, organise the power they already have in practice, or the movement collapses through political discouragement, division and confusion and falls prey to repression. In this case, the government and the class it represents then take back the initiative and their effective power. Such was also the situation in Belgium in the course of 1961.

During the strike, there was much talk of hardening the means of action. One of these means, proposed by André Renard but never applied, was the “abandonment of the tool”, i.e. the refusal to maintain the machines. On several occasions, threats were made to completely extinguish the blast furnaces of the steel industry. This measure was seen as the ultimate weapon to make employers and the government bend. The consequences for the economy would have been catastrophic: the extinction of the blast furnaces would solidify the steel and render it unusable for months. The economic cost of such a measure is astronomical. Most probably, there was never any real question of André Renard resorting to it: it was mainly a matter of “striking the spirits”, of reviving the movement, at a time when it was standing still and looking for a new direction.[5]

Reformist limitations

This threat also illustrates something else: for André Renard there was no question of the workers taking power. Renouncing the maintenance of the installations was the opposite of a takeover of the economy by the working class. To achieve this, it would have been necessary to transform the strike committees into committees of organisation, control and management of production, commerce, transport and administration. The strike committees should have been transformed into organs of power organisation. A power they already hold in reality. It was not a question of stopping maintenance, but of restarting production under workers’ control and in fact expropriating the capitalists.

3 January 1961 was a qualitative turning point for the general strike. During a speech at a mass meeting, André Renard launched the Walloon federalist objectives, i.e. the end of the unitary Belgian state with more political and economic autonomy for the Walloon and Flemish region, and rejected the call for a March on Brussels. Such a march would have had a unifying effect and could have united the working class in Flanders, Brussels and Wallonia. The idea of such a march had gained ground in many trade unions. La Gauche also popularised this perspective of struggle, as did the Jeune Garde Socialiste, the youth organisation of the PSB. However, Renard gave priority to the “Walloon retreat” (Repli Wallon). In a speech delivered during the strike, he declared that “from today, the words revolution and insurrection will have a practical meaning for us”.

However, these words remained without practical consequences, without action to make them concrete. It was then that André Renard revealed his political limits. In Marxist terminology, André Renard can be seen at best as a centrist: political leaders or currents in the labour movement who try to take an intermediate position between Marxism and reformism. In this case, revolutionary speeches and professions of faith are not followed by acts aimed at making this revolution possible.

André Renard went far in the direction of social transformation, but at the decisive moment he backed down. The explanation is that he had neither the programme nor the perspectives to achieve a socialist society. In the end, he diverted the objectives of the strike towards federalism, leading to a “Walloon withdrawal” from the general strike.

The “Walloon withdrawal”

The general strike had begun at the national level. It is true that its centre of gravity was in the Walloon industrial basins. However, the Flemish urban and industrial centres such as Ghent, Antwerp, Bruges and Ostend were still on strike when Renard swapped the objective of the strike, i.e. the rejection of the Loi Unique, for federalism. The return of the strike in Wallonia (“le repli Wallon”) was not only the result of the predominance of the CSC in Flanders (the CSC did not go on strike), but also of deliberate action by Renard and the Coordination des Régionales Wallonnes of the FGTB, a body coordinating exclusively the Walloon components of the socialist union.

André Renard was not only a Walloon leader but also a national leader. In Antwerp he was enthusiastically welcomed by thousands of strikers. During the 10 preparatory meetings for the general strike in Liège, one of the speakers was each time a Flemish trade unionist who spoke in… Flemish! The political and trade union federalism put forward by Renard met with resistance also in Liège but especially in Charleroi, the other centre of gravity of the strike. In Liège, the opposition was in a minority. Jacques Yerna, then secretary of the CGSP Gazelco (energy sector), openly regretted this turn of events.

In Charleroi, the change of course came up against the resistance of the socialist metal workers. Ernest Davister, then president of the FGTB delegation of the ACEC Charleroi metallurgical plant, expressed himself as follows:

“We went on strike against the Loi Unique. According to the Steelworkers FGTB of Charleroi, the change of objective in the middle of the strike was a deception towards the workers. On the one hand, we wanted to preserve the unity of the workers and, on the other hand, we tried to avoid any risk of Walloon nationalism which would have been as dangerous as Flemish nationalism.”

Consequences

It is true that at the end of the strike and afterwards, many Walloon workers no longer saw any prospect of a unified national struggle and were therefore attracted by federalism. This could have been avoided. An intense campaign by Walloon workers in Flanders during the first 10 days of the strike could have changed its direction. “Renard wanted a national strike and turned it into a Walloon strike,” said Georges Debunne, national president of the powerful socialist public services union.[6]

However, it is not enough to want a national strike – the methods used and the tactics are also decisive. Renard was not prepared for that. Of course, those mainly responsible for this division were the CSC and the Catholic Church, who did everything they could to prevent unity. The right-wing leaders of the FGTB also deliberately slowed down and ultimately sabotaged the strike in Flanders.

The strike was lifted after 35 days. It was while singing the Internationale and to the applause of those who had gone back to work earlier that the strikers went back to their jobs. Indeed, the hated Loi Unique was voted on and implemented.

The spirit of the ‘60s

These turbulent events shook the establishment, and ever since, the Belgian bourgeoisie has been haunted by the spectre of a new strike of the century. It felt the power of the working class. Among the most conscious layers of the working class, 60 years later, there is still something of the “spirit of the ‘60s”. The union leadership and that of the social-democratic parties SP and PS also remember the strike. Moreover, it is not clear who was more afraid of the strength of the workers’ movement: the bourgeoisie, the leaders of the Christian unions or the socialist leaders.

The radicalisation of broad sections of workers and young people following the general strike was politically extended in the elections that followed. These elections were won by the BSP and the Communist Party.[7] In 14 years after 1961, with one exception (the Vanden Boeynants-De Clercq cabinet, 1966-68), the liberals no longer participated in governments. The Mouvement Populaire Wallon, launched by André Renard, became one of the political vectors of federalist radicalisation in Wallonia.

Today, all the questions raised during this strike remain highly relevant. A general strike does not automatically and spontaneously bring answers to the questions it raises. Especially the question of working-class power posed by the indefinite general strike cannot be improvised – it has to be prepared in advance. This is the responsibility of the conscious and organised vanguard in the working class and the youth. By disseminating and discussing the lessons learned from events such as the general strike of 1960-1961, Vonk/Révolution, the Belgian section of the IMT, wants to ensure that future possibilities for transforming society are victorious.

Also recommended: Ted Grant’s article on the ‘Lessons of the Belgian Strike’

Notes

[1] https://www.marxists.org/nederlands/meynen/x/grote_staking.htm

[2] http://www.ihoes.be/PDF/Adrian_Thomas_Memoire_Web.pdf

[3] La Gauche and Links were established as part of the deep-entrist work of Ernest Mandel and the Fourth International at the time. Its aim was not to ‘propagandise Marxist ideas’ but to develop a ‘general left tendency’ in the PSB. As internal documents confirm, the section of the Fourth International decided to put forward “only demands and slogans, which can be supported by a public figure of the left”. This meant in practice and in theory, the tail-ending of confused left reformists of all strands.

[4] La Gauche, 3/12/1959

[5] http://www.patrimoineindustriel.be/public/files/Newsletter/newsletter-20/ihoes602.pdf

[6] Vechten voor onze rechten, Kritak, 1985.

[7] The Communist Party (PCB) had 30 something workplace branches in 1960, especially amongst industrial workers (metal, steel and portworkers). When the public service unions launched the indefinite strike, the PCB took initiatives with the aim of spreading the strike in the private sector, often against the will of the trade union leaders. But the PCB limited the aims of the general strike to trade-union demands such as the withdrawal of the Loi Unique and refused to see the revolutionary potential of the situation.