In the bourgeois media today, Afghanistan is portrayed only in relation to Islamic fundamentalism, jihad, warlords and drug cartels. While these ills are a sad fact of life in Afghanistan today, that was not always the case. 40 years ago, a revolution almost shook the country out of its backwardness, only to be thrown back after the imperialist-backed, fundamentalist counter-revolution. To understand the current situation in the Middle East, as well as the rise of the reactionary forces, it is necessary to understand the rise and fall of the Saur revolution in Afghanistan in 1978.

Historical background

Afghanistan is a geographically important country. As Engels observed:

“The geographical position of Afghanistan, and the peculiar character of the people, invest the country with a political importance that can scarcely be overestimated in the affairs of Central Asia”.

The country links Central Asia with South Asia and its geographical position played a very important role in the affairs of the country, which remains true to this day. In the 20th century, the country was a buffer zone between British India and the Czarist Russia. The British tried to occupy it but didn’t succeed completely. Nevertheless, they succeeded in occupying a part of the Pashtun region and bringing it under its domain through British India. Later, this wound of division would have significant consequences and was used by America and Pakistan to counter the revolution and control the country.

At the beginning of the 20th century, King Amanullah – an anti-imperialist inspired by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk in Turkey – tried to modernise Afghanistan but didn’t succeed. As Trotsky remarked on the situation at the time:

“Here is another nation in the East which deserves special mention today […]. This is Afghanistan. Dramatic events are taking place there and the hand of British imperialism is embroiled in these events. Afghanistan is a backward country. Afghanistan is making its first step to Europeanize itself and guarantee its independence on a more cultured basis. The progressive nationalist elements of Afghanistan are in power and so British diplomacy mobilizes and arms everything which is in any way reactionary both in that country and along its borders with India and throws all this against the progressive elements in Kabul. Starting from the decrees by which not only the bourgeois but also the social-democratic authorities in Germany banned May Day demonstrations, passing through events in China and Afghanistan we can see everywhere the parties of the Second International behind the work of suppression and oppression. For, you know, the onslaught against Kabul organized with British resources, takes place under the government of the pacifist MacDonald.” (Leon Trotsky: April 1923)

Apart from imperialist aggression, Amanullah’s failure to modernise Afghanistan was due to the absence of a national bourgeoisie, the class that carried out the industrial revolution in Europe, and founded the nation states.

At the time of the revolution in 1978, Afghanistan was surrounded by important countries like the Soviet Union, Iran, China and Pakistan. Later these countries actively participated in the revolution and counter-revolution in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan and the colonial revolution

In many parts of the world, including the neighboring country of Pakistan, 1968 was the year of mass movements and protests. Afghanistan was not an exception. The year 1968 saw a wave of student and workers’ strikes. The students’ demands included education and curriculum reform, protests against admission policies, etc. The workers’ demands included wage increases, better working conditions, holidays, fewer working hours, health and medical insurance.

The renowned historian of Afghan history, Louise Dupree described the situation in these words:

“The occasional student support – even in some cases, support by the grammar school students – for the workers’ strike has surprised many in Kabul.”

The level of consciousness among the students was high:

“In some classrooms, the students often refuse to listen to anti-Marxist views, and an atmosphere has been created in which few academics can favourably discuss anything relating to the West.”

Revolution is contagious and Dupree admits this by saying:

“The existing state of communications today encourage, I believe, the rise of worldwide student-worker demonstrations. The news of a ‘police bust’ at Berkeley, of a riot in Columbia, or of students and workers at the barricades in Paris sweep around the world in hours – and every town and many villages in Afghanistan have their quota of transistor radios. The student disturbances in Afghanistan can be seen as an extension and part of the general student unrest throughout the world.”

The comments about the effect of the workers’ uprisings across the world are true, but behind all of this was also the organised work of the PDPA (People Democratic Party of Afghanistan), as it was the party’s strategy to carry out political work among the workers.

Marx didn’t focus much on the problems of revolution in the colonial countries as he envisaged it first in the advanced industrialised countries. This was not by chance as, at that time, Europe was at the centre of world revolution.

In the colonial and ex-colonial countries it is impossible to progress further on the basis of the old social relations. In all these countries the problems of the national democratic revolution, the agrarian revolution, the liquidation of feudal and pre-feudal remains, cannot be solved along the lines of the classical bourgeois revolutions of France 1789. The bourgeoisie of the colonial countries had come too late into existence in a situation where capitalist relations were already dominating the globe. For this reason the national bourgeoisie in the colonial countries was unable to play any progressive role like the Western bourgeoisie played in the development of capitalist society in their respective countries hundreds of years earlier.

The bourgeoisie developed too late in Afghanistan and was too weak to play a progressive role / Image: public domain

The bourgeoisie developed too late in Afghanistan and was too weak to play a progressive role / Image: public domain

The bourgeoisie in the colonial countries is too weak, their own resources are too narrow to compete with the industrial economies of the capitalist West. In short, they are bound by a thousand threads to the old society on the one hand and imperialism on the other, thereby making them a force in defence of the status quo. Thus, history placed the task of national democratic revolution against the feudal remains and socialist revolution against the bourgeoisie simultaneously on the shoulders of the proletariat.

The rottenness of the social relations, the relative weakness of imperialism and the mighty growth of industry and stabilization of China in the post-war period led to great social upheaval and revolutions in the colonial countries. But the Stalinist degeneration of the Russian Revolution, and the Stalinist deformation of the Chinese Revolution from its very beginning, in spite of its achievements, meant in its turn that the revolution in the colonial countries began with nationally limited perspectives and with fundamental deformations from the start. This was the background of the revolution in Afghanistan and in turn the basis of its failure and victory of the counter-revolution, which I will explain here.

The PDPA

The People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan was founded on 1 January 1965 in the house of Party leader Nur Muhammed Tarakai. The aim of the party was described in these words:

“We know that we are struggling for some classes against some classes and that we are going to build such a society on the basis of social principles in the interest of the toilers which is void of individual exploitation.” (Address to the first congress of the PDPA).

But soon after its foundation, the party faced a split in 1967 mainly on the question of opposition to the king.

The two main groups that emerged, named after their respective papers – though both followed the theoretical lines of the Soviet Union – was the Parcham (The Flag) oriented more towards nationalism. Its base was mainly within the urban middle classes and their work was more concentrated in the armed forces. On the other hand, the focus of the Khalq (The People) faction was on class lines and its base was in the urban working class and rural poor.

There exists a popular myth even among some lefts that the PDPA didn’t have any mass base at all. But serious Afghan historians do not agree with that position, and they are of the opinion that the PDPA had mass support even in rural Afghanistan. Apart from that, there is evidence that the PDPA had succeeded in establishing study circles even in the Pashtun region across the border in Pakistan.

The Revolution

In 1973 Daud – a cousin of the king and a Pashtun in political orientation – came to power through a palace coup, with the active support of Parcham and the army, and officially ended the monarchy. Daud had close relations with the Soviet Union. In the beginning of the Daud regime the communists enjoyed freedom of activity. But after the reunification of the PDPA in 1977 and their growing influence in the civil and military bureaucracy, they became a threat to the regime.

On 18 April 1978 trade unionist and leader of Parcham, Mir Akbar Khyber, was mysteriously assassinated. Thousands of people gathered at his funeral in Kabul. Mir Akbar Khyber’s death and funeral were a warning to the regime. And this, the life-or-death struggle between the regime and the PDPA intensified. Ten days later on 28 April 1978, the PDPA took state power in a coup, this time led by the Khalq faction.

It is interesting that neither faction of the PDPA had any perspective and were not expecting a revolution in the near future in Afghanistan. The same was true of the Soviet Union. The revolution was a surprise for the Soviet bureaucracy. The revolution was provoked by the Daud regime’s suppression of the PDPA. It became a simple question of survival for the PDPA. After Mir Akbar Khyber’s assassination, the purge against the communists was sped up. The regime arrested party members, including party leader Nur Muhammad Tarakey at midnight on 26 April. This was a fatal move by the Daud regime.

Next morning a pre-planned operation, specifically designed for use in case of such an event, was initiated by the PDPA. Around 250 tanks and armoured vehicles took part in the coup, and officers who were members of the party took charge of both ground and air forces. By 5:30pm, power was in the hands of the rebels. The arrested party leader was released from jail as a victor. Radio Kabul, as well as Bigram and Kabul airports, were under their control. That evening they announced the victory of the revolution on Radio Kabul.

The Saur Revolution (Saur being the name of the Afghan calendar month in which the revolution occurred) in Afghanistan was not like that in Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917, where power was taken by a mass uprising of workers and peasants led by Lenin and Trotsky. To characterise such a phenomenon as we saw in Afghanistan, the British Marxist Ted Grant developed the term Proletarian Bonapartism. It is a situation where capitalism and landlordism have been abolished and the commanding heights of the economy have been nationalised, but power is not in the hands of the workers and is instead held by a one-party military-police dictatorship.

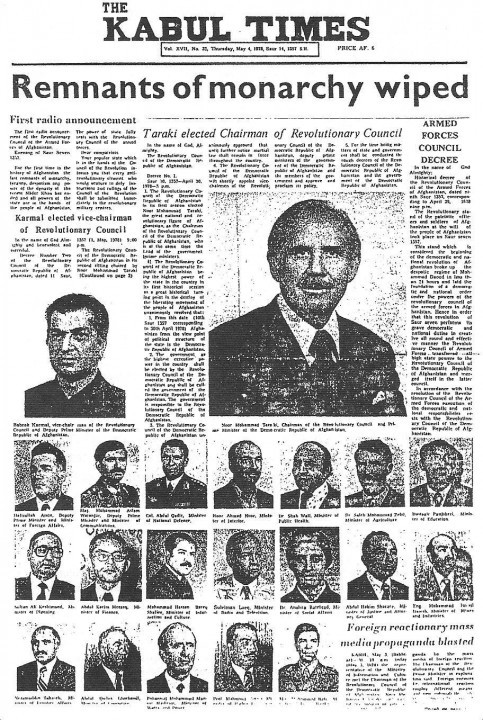

Leaders of the Saur Revolution modelled themselves on the Soviet Union / Image: Cleric77

Leaders of the Saur Revolution modelled themselves on the Soviet Union / Image: Cleric77

Ted Grant described the coup as such:

“The coup was precipitated by Daoud’s attempt to suppress all opposition. His overthrown regime had been a one-party feudal-bureaucratic regime. The country’s small working class had no trade union organisations.

“Had the revolution taken the healthy form of a movement of the masses themselves, the result would have been very different from what actually happened in Afghanistan. The April 1978 coup was based on a movement of the elite of the army and the intellectuals and the top layers of professional middle-class people in the cities.

“They organised the coup first of all as a preventative measure against attempts which were being prepared to exterminate them and their families. They acted from self-preservation, but also with the idea of bringing Afghanistan into the modern world.”

Finding themselves in power after the collapse of the previous rotten regime, the officers, opposed by imperialism and the feudal classes, could only find support amongst the small working class and the impoverished working masses. They found a suitable model in the Soviet Union, which had a planned economy but which, conveniently for the military leaders, had a top-down totalitarian political system.

The struggle for the emancipation of Afghanistan

The PDPA inherited a country in grim conditions. The social problems were deep and wide. It was one of the poorest countries in the world. At the time of the revolution the population of the country was around 15.1 million, of which only 14 percent were living in urban centres. The rest of the 13 million were living in rural areas, and 1.5 million of the rural population were nomads.

Illiteracy was astonishingly high, affecting 95 percent of the population. A landlocked country, with a total area of 160 million acres of which only 12 percent was arable, 60 percent of the arable land was left uncultivated each year partly because of a lack of water and partly because of the inefficiency of the backward, feudal system, which dominated the countryside. This was a damning condemnation of imperialism and the feudal classes, which had dominated the country until then.

The PDPA government estimated that 45 percent of arable land was in the hands of 5 percent of the landowners. The peasants and farmers were living in miserable conditions under the burden of heavy debts mainly owed to individual landlords and big farmers.

The new regime inherited many problems, given the country’s backwardness, but still managed to carry out some reforms / Image: IDoM

The new regime inherited many problems, given the country’s backwardness, but still managed to carry out some reforms / Image: IDoM

The countryside was socially backward, with tribal codes of conduct mixed with a distorted form of Islam. Socially and economically, the clergy was weak and came from the lower strata of society. A physical infrastructure was almost absent. The fact that in 1978 not a single village had electricity, reveals the dire conditions of the infrastructure. In terms of health, education, communications and other social and physical infrastructure, Afghanistan was one of the most backward countries in the world.

The industrial base was weak, and industrial production was only 17 percent of GDP, which could meet only 10-15 percent of consumer demand for sugar, textile, footwear, etc. The industrial proletariat amounted to a mere 40 to 50 thousand and was concentrated in four or five urban centres. The major urban and industrial centre was the capital, Kabul.

Half the workforce was employed in factories with a workforce of more than 1,000. Although trade unions were illegal, during the strike wave of 1968-69 the largest factories went on strike which shows the militant character of the movement.

Despite the immensely difficult conditions facing the PDPA regime after taking power, it was determined to change the fate of Afghanistan. Immediately after the takeover, the PDPA started a series of radical reforms.

The first significant act was the nationalization of industry. After a few years this policy showed its result in terms of industrial production. For example in 1978 the processing and mining industry only contributed 3.3 percent of the national income. In 1983 it reached 10 percent.

Decree no. 6 abolished the debts of peasants owed to rich farmers and landlords, lifting an enormous burden from the shoulders of the poor peasants which had weighed on them for centuries.

Decree no. 7 introduced marriage reforms. A significant one was the abolition of ‘bride price’: a centuries old social practice. This decree also introduced the age of consent.

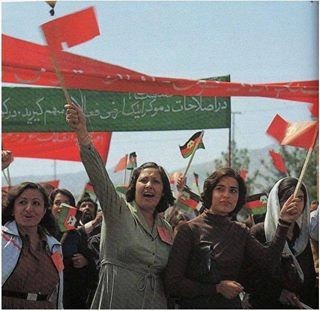

There were many reforms for women / Public domain

There were many reforms for women / Public domain

Land was distributed and collective farming was introduced. Limits were imposed on the ownership of land. These were extremely important reforms in terms of social and economic justice, but even more so from the point of view of improving agricultural output. After the first year in power it was estimated that 822,500 acres had been distributed to 132,000 families. Water distribution, which previously was the responsibility of individual men or families, was taken into state hands under the Ministry of Agriculture.

Similar reforms were introduced to eradicate illiteracy. One significant reform on this front was the nationalization of the printing presses, which was important in increasing the availability of educational material, but it also made it possible to prepare teaching and educational materials in small regional native languages.

Equal rights for women were implemented as well as paid maternity leave. Reforms like these were unheard of in the whole region. The introduction of a planned economy soon showed its tremendous results in the different spheres of the economy. For example, 100 new factories were built in the five years leading up to 1983. In terms of infrastructure there was an 84 percent increase in hospital beds, and a 45 percent increase in available doctors. The power and privileges of the possessed classes were badly damaged, and the interests of imperialism were under threat.

Counter-revolution

Capitalism is one, interconnected economic system across the globe. Thus, a threat to capitalism in a tiny and economically very backward country was unacceptable to the strategists of capitalism. The first year after the revolution went relatively well. A common misconception, however, is that American imperialism only started to intervene after the intervention of the Soviet Union. The reality is, that American imperialism started working on its strategy to counter the revolution long before the Soviet intervention. At the time of the American intervention the strategists of American imperialism were of the opinion that the Soviet Union would not intervene. In the spring of 1979 American imperialism started to mobilise its reactionary machinery. The CIA sent its first classified proposal to President Jimmy Carter in March 1979 to support the counter-revolution in Afghanistan. The Americans reached out to Saudi Arabia and Pakistan to devise a strategy for counter-revolution. The dollars and liberalism of the Western world, combined with the Wahhabism of Saudi Arabia, supported strategically by the Pakistan military dictator General Zia ul Haq, formed an unholy alliance to counter the revolution.

That summer the Carter administration authorised the CIA to spend $500,000 on the campaign. As time passed every significant capitalist country contributed in one way or another to create the Frankenstein’s monster of Islamic fundamentalism to fight against the revolution – monster that is haunting its former masters to this day. Today the Western media portrays Islamic fundamentalism as if they had nothing to do with it. But in reality the fundamentalists of today are the direct result of western imperialist policies.

Difficulties

The Saur Revolution had its own peculiar weaknesses. One was objective: The deep economic and social backwardness of the country, which meant that the small working class played no independent role in the revolution – a necessity for a successful socialist revolution. In the absence of an international revolution, the Saur Revolution was isolated and the criminal Stalinist theory of the possibility of building socialism in a single country to overcome its social economic problems worsened this situation.

The other weakness was the organization of the PDPA. The party had never developed into a coherent Leninist organisation and soon after taking power the internal struggle for power started along factional lines. But the factional split was also fuelled by the intervention of the Soviet Union. In fact the bureaucracy of the Soviet Union played a very reactionary role by actively taking part in the factional struggle within the PDPA. They supported the Parcham wing against the Khalq. The Khalq faction strongly opposed the intervention of the Soviet Union and warned them that it would have dire consequences.

But in December 1979 the Soviet Union intervened militarily. The Parcham faction was brought to power and a purge against the Khalq faction was begun that weakened the party’s grip on power. The internal conflict had already been building up during the summer.

The Khalq faction had the illusion that by taking a non-aligned position in its foreign policy they could create a friendly environment for the new regime. In reality, with the intervention of the Soviet Union, Afghanistan became the battleground of two world powers. And Afghanistan quickly proved to be a quagmire for the Soviet forces.

The victory of counter-revolution

Little by little, all the reforms were rolled back as the regime was trying to reconcile with the opposition, and in 1988 the Soviet Union withdrew. The regime was extremely weak by then and in 1992 the Mujahideen took over. Later, rank-and-file members of the Mujahideen created a Pakistan-backed rebel group, known today by the name of Taliban, which took power and brutally assassinated the head of the Parcham regime Najibullah.

Imperialism funded the Mujihadeen counter-revolution. Some of these ‘freedom fighters’ later became the Taliban / Image: public domain

Imperialism funded the Mujihadeen counter-revolution. Some of these ‘freedom fighters’ later became the Taliban / Image: public domain

The following 26 year-long fundamentalist counter-revolution pushed Afghanistan back into barbarism. The counter-revolution not only affected Afghanistan but the whole region, especially Pakistan. Heroin was used as a means to finance the counter-revolution and the Mujahideen. Today that strategy has created the first narcotics-state in the world. It is estimated that today 500,000 acres in Afghanistan are devoted to the production of opium poppies. In 2017 the opium harvest was 9,000 tons.

The Afghan Saur Revolution represented the hope of emancipation from the misery and oppression of landlordism and capitalism for the people of Afghanistan and the entire region. That hope was drowned in blood by imperialism. Today, if we want to defeat these reactionaries, the only option is to reorganise on class lines. The only revenge for the miseries brought to bear on the Afghan people is to bring to life a socialist revolution against the decades-old counter-revolution. This is the only option for pulling not only Afghan society but also Pakistan from the claws of barbarism created by capitalism and imperialism. This historical task lies on the shoulders of the working class of the region and the advanced capitalist world in general. To achieve this it is vital to build the organization of the working class on an international basis.

Source: Afghan Saur Revolution 1978: what it achieved, how it was crushed