At 3am on Wednesday, November 4, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed appeared on state television to declare a six-month state of emergency in the country’s northern Tigray region. According to Abiy, the Tigray regional security forces had committed ‘treason’ by attacking federal military bases in the regional capital Mekelle as well as Dansha, killing and injuring an unspecified number of soldiers in the process. This announcement set in motion a chain of events which could eventually lead to the breakup of Ethiopia itself with far-reaching consequences for the Horn of Africa.

Shortly after, the Ethiopian Air Force started airstrikes and bombing raids around Mekelle and troops from all over the country converged on Tigray. Since then, Abiy’s government has purged Tigrayan officials from government positions and mobilised ethnic militias to join the war. Immediately, Sudan closed its border to Ethiopia, signalling the regional consequences of the conflict. The war has not started well for the prime minister, however, with his forces suffering serious casualties in the first week of fighting. As a result, after only 5 days he has sacked his army chief, head of intelligence and foreign minister. The Ethiopian Prime Minister, who won the Nobel Peace Price in 2019, boldly declared that the operation will continue “until the junta is made accountable by law.” All internet and telecommunications were cut off to the region and a no-fly zone has been imposed.

‘Unexpected war’?

The country’s deputy chief of the army, Birhanu Jula, said on state television that the country “has entered into an unexpected war” and that “our country has entered into a war that it did not want. This war is a shameful war. It does not have a point. The people of Tigray and its youth and its security forces should not die for this pointless war. Ethiopia is their country.”

It is often stated that the truth is the first casualty of war. This war was prepared months in advance; there is nothing ‘unexpected’ about it. Despite the prime minister’s claims that his soldiers were ‘ambushed’ and ‘pushed’ into the war, preparations for it, as well as the eventual escalation, had been made well in advance. Large-scale movements of federal troops heading northwards were reported days before the official commencement of hostilities. The matter of ‘who fired first’ is not a criterion to analyse the question of war, as at some stage a pretext would have been found to justify the commencement of the conflict. The real question we must answer is: what are the material and class interests involved?

‘Ethnic Federalism’

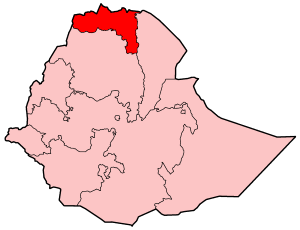

Tigray is the region of the Tigrayan people who make up about 6 percent of the country’s population of more than 110 million. Despite their numerical minority, politicians from the Tigrayan ethnic group have enjoyed disproportionate power and influence in the federal government for the last almost three decades.

The Tigrayan people make up about 6 percent of the country’s population of more than 110 million / Image: Golbez

The Tigrayan people make up about 6 percent of the country’s population of more than 110 million / Image: Golbez

After fighting against the Derg military regime that ruled Ethiopia in the 1970s and 1980s, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (the TPLF) emerged as the leader of the coalition that took power in the country in 1991 when the junta was overthrown. The ruling cliques entered into this ‘ethnic’ federation claiming that this will ‘prevent the breakup of the country.’ The coalition, known as the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) consisted of four main political parties, largely split along ethnic and geographic lines. It followed a federalist approach that gave significant power to Ethiopia’s regions, but the coalition controlled all levers of power and repressed almost all political opposition. While there is a central government, its constituent parts are carved out along ethnic lines, but this system has allowed political power in Ethiopia to be concentrated in the hands of a few.

Meles Zenawi, a Tigrayan, led Ethiopia from 1991 until his death in 2012. This coincided with a massive state-led economic boom which allowed the ruling clique to stabilise the situation for a while. This explosive economic growth, however, came at a huge cost. Almost all the wealth flowed into the pockets of the rich sitting in the capital, Addis Ababa. The city itself grew at breakneck speed, propelled by massive Chinese investment, which led to deep resentment in the different ethnic regions which lost out. Mass protests erupted in 2015 among the Oromo people in the populous Oromia region, but the immediate demands of the protests against ‘land grabs’ quickly drew in broader political demands such as the release of political prisoners and for more rights for the Oromo, the largest ethnic group, making up 34 percent of the population.

Protests then spread to the Amhara people, the country’s second largest ethnic group. These uprisings weakened the ruling TPLF and propelled Abiy Ahmed from the Oromo into the prime minister’s office in 2018. Soon after, members of the Tigray ethnic group were purged from positions of power and arrested in corruption and security-related crackdowns, opening a deep chasm between the Tigray region and the federal government.

The immediate cause

A long-simmering feud between the federal government and the powerful faction in control of Tigray has been barreling toward a violent confrontation for months. The country was supposed to hold national elections this year but with the breakout of the Covid-19 pandemic, the election board postponed the vote beyond the expiry of Abiy government’s mandate in October 2020. In response, the ruling party used its dominance in the upper house of parliament to extend Abiy’s mandate indefinitely. In what the opposition considered a power grab, it was now up to the administration to decide when elections would be held and for how long it would govern. The backlash was felt most strongly from those parties representing the Oromo and the Tigrayans which had proposed that Abiy would enter into a power-sharing agreement until the next elections. But Abiy, seeing this as a golden opportunity to carry out his ambitious plans, had other ideas.

Nationalist chauvinism was whipped up by the leadership of the different regions. This reached fever-pitch in June with the assassination of well-known Oromo singer and political activist Hachalu Hundessa. As the protests swelled, Abiy’s government began arresting opposition figures it accused of fomenting the unrest and ensuing communal violence, but Abiy used the opportunity to clamp down on his rivals from all nationalities, including his Oromo rivals.

The elections were then postponed until next year, but Tigrayans refused to recognize Abiy’s extended rule and went ahead with regional elections in September. As a result, the federal government in Addis Ababa is not recognising the regional government and in turn the regional government does not recognize the federal government. The federal government then withheld budget transfers earmarked for the Tigray to squeeze what it sees as a “rogue state.” It was already clear at this stage that some sort of armed conflict was coming.

The ambition of Abiy Ahmed

Abiy Ahmed represents a section of the Oromo elite. The young prime minister is an extremely ambitious member of the bourgeoisie. His vision is to centralise power and unify the country by increasing the federal government’s power and minimising the autonomy of the regional governments. Abiy sees ethnic federalism as a fetter holding the country back and he is prepared to ride roughshod over any nationalist sentiment to achieve his goals, but Tigray and other regions and ethnic groups have openly resisted this.

Abiy is a ‘reformer’ from a bourgeois point of view. He wants to upend the normal workings of Ethiopian capitalism, but to enact his desired political, economic and social reforms he needs the central government to have more power. To that end, Abiy began dissolving several ethnic parties into his new pan-Ethiopian Prosperity Party last year, with the goal of moving Ethiopia away from ethnic politics, closer to a kind of secular federalism.

Abiy’s ultimate goal is to establish Ethiopia as the undisputed powerhouse of East Africa. Since coming to power two years ago, he has made sweeping reforms, but in order to achieve his goals, he first wants to centralise and unify the country. To fully concentrate on this immediate task he temporarily ended long running hostilities with neighbouring Eritrea and he has played a role in mediating regional conflicts between nations including Sudan, South Sudan, Djibouti, Kenya and Somalia. This earned him the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize in 2019.

Abiy temporarily ended long running hostilities with neighbouring nations, earning him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 / Image: Bair175

Abiy temporarily ended long running hostilities with neighbouring nations, earning him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 / Image: Bair175

As part of a vision to centralise power in Ethiopia he launched the Prosperity Party last year, which has brought together members of the former ruling coalition — with the exception of the Tigray — along with previously excluded ethnic groups. While he projects the image of a peaceful reformer outside, Abiy has mercilessly clamped down on his opponents inside Ethiopia. He has detained opposition leaders and killed hundreds of opponents from different ethnic groups.

The EPRDF was a coalition of four ethnic-based parties that represented the largest ethnic regions in the country. His new Prosperity Party, on the other hand, is a single unitary entity with no formal and institutionalized representation for ethnic groups. This represents a radical blow to the previous inter-nation peace, that was central to the previous political settlement. This unscrupulous move to dissolve the EPRDF and create the PP angered not only the TPLF but also Abiy’s own Oromo constituency and much of the people of the historically subjugated South.

The creation of the Prosperity Party was driven not just by Abiy’s desire to create a new political party totally subordinate to him but also motivated by the need to drive his ambitious plan through. In order to achieve this goal, he needed to weaken two of the most powerful obstacles to his agenda — the TPLF and the Oromo opposition, in particular the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF).

Imperialist interests

Looming behind these events are rival imperialist interests. Over the course of the last decade, Ethiopia has become increasingly dependent on Chinese investment. The Export-Import Bank of China put up 2.9-billion dollars of the 3.4-billion dollar railway project connecting Ethiopia to Djibouti, providing the landlocked country access to ports. Chinese funds were also instrumental in the construction of Ethiopia’s first six-lane highway (an 800-million dollar project), as well as a metro system and several skyscrapers dotting Addis Ababa’s skyline. Beijing also accounts for nearly half of Ethiopia’s external debt and has lent at least 13.7 billion dollars to Ethiopia between 2000 and 2018.

Beijing has financed mega-projects from hydropower dams to skyscrapers. Now, Western imperialism has since woken up to the prospects of huge profits to be made in Ethiopia, but recent efforts by Abiy Ahmed to privatise state-owned companies and reduce the country’s debt burden are shifting the power dynamics in the country. For his part, Abiy is prepared to play off China against the West to leverage competition between the West and China to attract even greater investment and reduce the country’s dependence on Beijing.

Chinese funds were instrumental in the construction of Ethiopia’s first six-lane highway, as well as a metro system and several skyscrapers in Addis Ababa / Image: Laika ac

Chinese funds were instrumental in the construction of Ethiopia’s first six-lane highway, as well as a metro system and several skyscrapers in Addis Ababa / Image: Laika ac

In December 2019, Ethiopia received a 9 billion dollar injection of financial aid from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The influx of cash could disrupt 15 years of increasing Chinese dominance. “The granting of this money sees the West countering China in a very tangible way, in one of the more politically and economically important and consequential countries in Africa,” said Zemedeneh Negatu, an Ethiopian-American investor and global chairman of the Fairfax Africa Fund. The IMF’s loan was the first time in over a decade the Fund lent money to Ethiopia. The amount also represents one of the highest levels of financial assistance that can be provided under the organisation’s lending rules.

A core part of Abiy’s agenda is an effort to overhaul the country’s economic model of heavy state investment. As part of that push, the prime minister has surrounded himself with Western-educated technocrats with international experience to raise private capital and privatise key sectors such as the telecommunications market. He is clearly taken in by the interest from the West, particularly after flattering him with the Nobel Peace Prize. This has gone a long way toward propelling his image onto the world stage. In the Western media he has become the poster child of a ‘modern Africa full of economic potential’. They are showering him with accolades and favourable loan agreements.

The reforms are creating opportunities for Western businesses to invest in Ethiopia even as they are altering Ethiopia’s relationship with China. Speaking at a conference in Addis Ababa in December, Abiy went as far as to say the terms of Chinese loans had damaged the Ethiopian economy.

“There are some that say we are adding more debt to the country’s already high debt. But borrowing from the IMF and the World Bank is like borrowing from one’s mother. What hurts Ethiopia is borrowing from other companies or some countries. For instance, Ethiopia borrowed to build a railway but was asked to repay the debt before the completion of the construction,” he added, referring to the Chinese-backed railway line to Djibouti.

European and American companies are lining up. In December, Abiy received European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. The previous month, Adam Boehler, the CEO of America’s International Development Finance Corporation, the investment branch of the US government, said Washington is “prepared to make multibillion-dollar investments in Ethiopia.”

Such high-profile visits indicate the growing interest from Western countries alongside China, the Gulf States and Russia, which have all been maneuvering for influence in Ethiopia since its economy started to boom about a decade ago. One of the most visible pledges came in 2018 through a 3 billion dollar package of aid and investment from the United Arab Emirates, though China and Ethiopia continue to enjoy robust trade and investment relations.

The strategy pursued by Abiy to play off Beijing against the West, however, has reached its limits. Recently, relations between the US and Ethiopia took a wrong turn after the Trump administration’s decision to suspend and delay development assistance to Ethiopia over the filling of the new Grand Renaissance Dam on the banks of the Nile river. This is a vital project in Abiy’s plans for Ethiopia, but the decision by Trump was intended to push Ethiopia into accepting a negotiated solution favoured by Egypt. Trump also suggested that Egypt could even ultimately blow up the dam if a deal was not reached. Likewise, Beijing has begun to reduce the amount it lends to Ethiopia in recent years – from 1.47 billion dollars in the 12 months from July 2014 to 630 million dollars in 2017. Now Abiy feels he is increasingly being boxed into a corner. The economy was already in decline before Covid-19 but Ethiopia now faces mounting economic and social crises. The military operation in Tigray is a desperate gamble to centralise political power and expedite the process for his ambitious plans. Ultimately, the escalation of the conflict would also kill remaining hope for the democratic reforms he has claimed to be pursuing.

Socialism or Barbarism

Abiy’s top-down, unilateral pan-Ethiopian reform effort has deeply destabilised the whole political situation and might in the long run lead to the breakup of the country. This will be accomplished with barbarism on an unimaginable scale. On the first Sunday after the commencement of hostilities, a massacre took place in which 54 people were killed in a schoolyard in the village of Gawa Qanqa. Survivors said the assailants specifically targeted members of the Amhara ethnic group and that victims “were dragged from their homes and taken to a school, where they were killed”. Most of the victims were women, children and elderly people, according to survivors who hid in nearby forests. On 9 November, hundreds of bodies were found in the town centre in Mai-Kadra, a town in the south-west area of the Tigray. All the victims appeared to be from the Amhara ethnic group.

The military offensive comes at a time when the federal government faces serious crises on multiple fronts. Besides battling the pandemic and working to boost a debt-laden economy, it is confronting disaffection within his own Oromo ethnic community. Many Oromo have also criticised his government’s crackdown on them, following the ethnic violence that resulted from the killing in June of a prominent Oromo singer, Hachalu Hundessa.

A protracted war will have the opposite effect of what Abiy envisages for Ethiopia. The army’s Northern Command is predominantly Tigrayan and has developed close ties with the TPLF. This explains why the bulk of the federal fighting force is drawn from a plethora of ethnic armies from the regional states. Tigrayan forces number up to 250,000 men and have their own significant stocks of military hardware as well as decades of fighting experience. It has great resources, a battle-hardened society and it controls large swathes of territory from which it can organise and launch a concerted military attack. One of the likeliest possibilities is that the army will split along ethnic lines, with Tigrayan officers defecting to their region’s own force. There are signs that it is already happening.

“The fragmentation of Ethiopia would be the largest state collapse in modern history,” a group of former United States diplomats said in a statement published by the US Institute of Peace on Thursday. This is a serious possibility.

The current war with TPLF not only represents a significant threat to the integrity and cohesion of the Ethiopian state and its people. The war with TPLF could drag on for years, with no clear winner. To add to this, there is still low-level insurgency in West and Southern Oromia. The war could also encourage other groups elsewhere in the country, particularly in areas where there is significant opposition to Abiy’s vision to resort to armed rebellion.

Finally, whichever way the war ends, the confrontation between Abiy and TPLF will have profound ramifications.The UN has warned of a major humanitarian crisis if as many as 9 million people flee. This would reverberate across Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa for decades to come. It is likely to define the very structure, character, and identity of Ethiopia and the region for years to come. A full-blown war in Ethiopia would severely affect the six countries that surround it. The violence in Tigray could draw in nearby Eritrea, which is now allied with Ethiopia’s federal government and has a long-established resentment toward the TPLF. Many veterans from the TPLF who participated in the Ethiopian-Eritrean war between 1998 and 2000 are now part of the Tigray region’s paramilitary forces.

This barbarism is what capitalism has in store, in its period of death agony. The people Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia and in the Horn of Africa generally have suffered from brutal conflicts for decades; a civil war in Ethiopia has the potential to further deepen the barbarism in the region. The only way out for the people in the region — and for the African people generally — is the path of revolution. A successful revolution in a key country like South Africa or Nigeria will present a beacon for the whole continent. The working class has no nationality and in Africa the artificial national lines are even more evident from the manner in which they were drawn up by the imperialists. At the same time, a socialist economy isolated in one part of Africa would be completely at the mercy of the capitalist world market. Therefore a socialist revolution can only be the opening shots of an all-African revolution as the first step towards a world socialist revolution.

Socialism is international or it is nothing. The interests of the working class in one part of the continent are no different from the interests of the workers throughout the world. The same exploitation and oppression which takes place here, takes place everywhere. As the crisis of world capitalism intensifies, the capitalist class also intensifies its attacks on the working class in order to protect its profits. This is the reason behind the rising tide of class struggle everywhere. Marxists are internationalists. We do not limit our organisations to the artificial borders of single nations, but build a world revolutionary organisation for the spreading of the ideas of Marxism and the defence of the interests of the working class everywhere.