We republish the first part of a pamphlet (first released in 1987, during the twilight of the Soviet regime), which serves as an invaluable introduction to the events from the October Revolution to the rise of Stalinism in Russia ‒ from which innumerable lessons can be drawn for the class struggle today.

Here, George Collins (then a member of the South African section of the Committee for a Workers’ International) explains how the workers and peasants of Russia, led by the Bolsheviks, took power in the name of the Soviets, and defended the fledgling regime against the forces of White counterrevolution in the Civil War.

The October Revolution

Petrograd, capital of Russia, on the night of October 25, 1917. With the First World War raging on the battlefields of Europe, the Russian Revolution has reached its deciding moment. Armed detachments of workers and soldiers, organized by the Bolshevik Party, have taken control in the city. The pro-capitalist Provisional Government, discredited and isolated, has ceased to exist.

In the Smolny Institute, formerly a girls’ school, the Congress of Soviets [elected councils] of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies is in session.

Some delegates are professional politicians, left-wing intellectuals or radicalized army officers. But the vast majority are representatives of the ordinary working people: “great masses of shabby soldiers, grimy workmen, peasants ‒ poor men, bent and scarred in the brute struggle for existence” (John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World) ‒ but filled with a revolutionary vision of the future, and a passionate determination to end their oppression once and for all.

Petrograd Soviet Assembly in 1917 / Image: fair use

Petrograd Soviet Assembly in 1917 / Image: fair use

Middle-class reformists denounce the Bolsheviks and demand that the congress break up! But delegate after delegate of the workers, peasants and soldiers drown them in the will and inspiration of the masses rising to their feet.

A soldier captures the mood: “I tell you, the Lettish soldiers have many times said: ‘No more resolutions! No more talk! We want deeds ‒ the power must be in our hands!'”

The hall, reports John Reed, “rocked with cheering…” (pages 102-103)

Amidst tumultuous applause, the Bolsheviks announce the transfer of state power to the soviets of the working people. A “Proclamation to workers, soldiers and peasants”, put forward by the Bolsheviks, is overwhelmingly adopted. It sums up the immediate tasks:

“The Soviet authority will at once propose an immediate democratic peace to all nations, and an immediate truce on all fronts. It will assure the free transfer of landlord, crown and monastery lands to the Land Committees [elected by the peasants as instruments for seizing the landlords’ estates], defend the soldiers’ rights, enforcing a complete democratization of the Army, establish workers’ control over production…take means to supply bread to the cities and articles of first necessity to the villages, and secure to all nationalities living in Russia a real right to independent existence.

“The Congress resolves: that all local power shall be transferred to the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, which must enforce revolutionary order.” (Quoted by John Reed, pages 115-116)

Under a government of the revolutionary workers’ party, supported by the mass of the poor peasants, the Russian people were freeing themselves from centuries of enslavement. In doing so they were demolishing the conditions for the existence of the capitalist system.

Lenin addressed the Congress the following evening. When eventually he could make himself heard above the thunderous applause, his first words were to confirm the task which the democratic revolution had placed on the agenda:

“We shall now proceed to construct the socialist order.”

Throughout the long, hard years of struggle leading up to this night, Marxists had explained in theory what this task would involve. Now the Bolshevik leaders needed to explain it in practical terms.

Leon Trotsky, next to Lenin the most authoritative leader of the Russian Revolution, spoke later that same night:

“We rest all our hope on the possibility that our revolution will unleash the European revolution. If the insurrectionary peoples of Europe do not crush imperialism, then we will be crushed…Either the Russian Revolution will raise the whirlwind of struggle in the west, or the capitalists of all countries will crush our revolution.” (Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, volume 3, page 315)

Red Guard of the Vulkan factory / Image: Wikimedia, fair use

Red Guard of the Vulkan factory / Image: Wikimedia, fair use

The delegates, wrote an observer, greeted these words “with an immense crusading acclaim”. Clearly, Lenin and Trotsky had expressed the thoughts and feelings of the vast majority of revolutionary fighters present in the Smolny that night.

Thus, in its very first hours, the new proletarian regime reasserted two fundamental propositions of Marxism ‒ no longer as theoretical concepts but as the basis for state policy:

(a) democracy and a solution to the land question, in an underdeveloped country like Russia, is possible only under working-class rule, bringing with it the overthrow of capitalism and the transition to socialism.

(b) Socialist revolution cannot be confined within the borders of one country; it can only advance through the struggle to overthrow capitalism on a world scale.

The rest of this pamphlet will deal with the fate of the Russian Revolution over the following ten to twenty years, and the displacement of workers’ democracy by a monstrous bureaucratic dictatorship. From studying these developments carefully, lessons can be learned that will be of vital importance to the struggle for the overthrow of capitalism today, and the construction of healthy regimes of workers’ democracy in the next period.

The Counter-Revolution

Marx and Engels had thought it most likely that capitalism would be defeated first in the developed countries, where the working-class was most powerful, and the industrial basis existed for the transition to socialism.

Instead, in October 1917, the chain of world capitalism broke at its weakest link.

The Bolshevik government inherited a backward society in a state of disintegration, exhausted by three years of war and a series of crushing defeats by Germany.

The imperialists could not tolerate the challenge to their authority, and the threat to their interests in Russia, which the Bolsheviks presented. As a pro-capitalist historian openly admits: “They [the imperialist leaders such as Churchill and Foch] warned that Bolshevism was a dangerous threat to world society and should be crushed while it was still weak”. (J.N. Westwood, Russia 1917 to 1964, page 38)

Within Russia the privileged and reactionary classes, as well as reformists in the labour movement, fought the revolution with every means at their disposal ‒ boycotts, economic sabotage, even the threat of a general strike.

Workers’ control over production, through a system of factory, regional and national committees, was proclaimed to provide some check on the capitalists’ activities. But there was no way of peacefully regulating the eruption of class struggle unleashed by the revolution.

On the one hand, the capitalists refused to submit to workers’ control. On the other hand, where the workers asserted their power, they did not stop at ‘controlling’ the capitalists. They took over factories lock, stock and barrel, even before their government was able to provide them with back-up and resources.

These struggles in industry clearly confirmed the perspective explained by Trotsky in his theory of “permanent revolution” (see Section 11): once the working-class takes power, even in a backward country, it becomes impossible to confine their program to the limits of capitalism. The workers will inevitably be driven on to the expropriation of the capitalists and the program of socialist transformation.

Bolsheviks massacred by Czechoslovak legionaries / Image: Lt. William C Jones

Bolsheviks massacred by Czechoslovak legionaries / Image: Lt. William C Jones

A bourgeois historian describes the deepening paralysis of Russian society as the struggle between the classes intensified:

“In the spring of 1918 the Russian economy was approaching the point of complete collapse. Money lost all value, manufactured goods disappeared from the shops, the shops themselves closed down as the normal channels of trade ceased to function; speculation and corruption were rife.” (Theodore H. von Laue, Why Lenin? Why Stalin? page 154)

Hunger worsened in the cities as food supplies came almost to a standstill: when manufactured goods could not be obtained even by barter, why should the peasants raise food for the urban market?

Revolutionary counter-measures were taken. The banks, in the face of their persistent sabotage, were occupied and nationalized in December 1917. The workers spontaneously took over more and more factories until the decree of June 1918 bringing every important branch of industry into state ownership.

Committees of the poor peasants, and armed detachments of workers, were organized to seize the grain supplies hoarded by the rich peasants (kulaks).

The irreconcilable struggle between the classes escalated into a full-scale trial of strength. Armed counter-revolution began to emerge, based on an alliance of the imperialist powers with the kulaks, the capitalists, and the remnants of the forces of Tsarism. The Russian civil war raged, with peaks and intervals, from May 1918 until the spring of 1921.

Civil war, like revolution, forces everyone to take sides ‒ for or against the government. Right-wing ‘socialists’, ex-revolutionaries and reformists, their hatred of Marxism (as always) stronger than their fear of reaction, in large numbers joined the onslaught against the workers’ state.

Red Guard detachment during the Civil War / Image: Wikimedia, fair use

Red Guard detachment during the Civil War / Image: Wikimedia, fair use

In March 1918, British forces occupied the northern port of Murmansk, and in August they seized Archangel, cutting off Russia’s outlets to the sea. In April, Japanese troops landed at Vladivostok in Eastern Siberia.

“Emboldened by the prospect of allied intervention,” writes the leading bourgeois historian, E.H. Carr, “the right SRs [right wing of the so-called Socialist Revolutionary Party, based on the richer peasants] at their party conference in Moscow in May 1918 openly advocated a policy designed ‘to overthrow the Bolshevik dictatorship and to establish a government based on universal suffrage and willing to accept Allied assistance in the war against Germany'” ‒ i.e. a pro-imperialist government! (The Bolshevik Revolution 1917-1923, page 170)

The Mensheviks, split in all directions, were “uncompromising only on one point ‒ their hostility to the [Bolshevik] regime”. (Carr, page 170)

In Samara, the SRs set up an anti-Bolshevik ‘government’ and started to raise an army. In August they captured Kazan. The Left SRs (based on the poor peasantry) were in coalition with the Bolsheviks until March 1918, when they left the government because they opposed the peace treaty signed with Germany, calling it a “betrayal”.

Now they plotted against the government and tried to provoke a German attack which, they believed, would be met with “revolutionary war”. Totally misreading the situation, they staged an insurrection in July, which rapidly collapsed.

Lenin speaking in 1919 / Image: Goldshtein G

Lenin speaking in 1919 / Image: Goldshtein G

The Western powers, as their war against Germany neared its end, concentrated their attention on Russia. More British, French and US troops were landed in Murmansk and Archangel. American, Japanese, British, French and Italian troops occupied Vladivostok and advanced westward as far as the Ural mountains. Sizeable French forces were deployed in the Black Sea.

At the same time, the imperialists financed and armed the counter-revolutionary (‘White’) armies organized out of the most backward peasantry by ex-Tsarist officers.

Victor Serge, a Bolshevik at the time, vividly describes the desperate situation in October 1919:

“The Whites under Admiral Kolchak are masters of Siberia; they constitute the ‘supreme government’ of Ukraine under General Denikin who is preparing for a march on Moscow. In the North, thanks to the British battalions, they dominate a vaguely socialist government presided over by old Tchaikovsky, a veteran of the first struggles against Tsarism; and General Yudenich is preparing to take Petrograd, where the people are dying of hunger in the streets and dead horses are piled up in fromt of the Grand Opera.” (From Lenin to Stalin, page 31)

Yet, a year later, Wrangel (Denikin’s successor) had been crushed in the Crimea, and the military threat was effectively ended.

The Bolsheviks’ victory over the combined forces of internal and external reaction, from a position of terrible weakness, most surely rank as one of the most brilliant military achievements of all time.

How was this victory won?

How the Bolsheviks Defeated the Counter-Revolution

The survival of the Russian workers’ state was made possible, in the first place, by the support of the working-class internationally in the enormous movements following the October revolution.

Brilliantly confirming the Bolsheviks’ perspective, Europe was plunged into a period of revolution. The road to victory opened up before the working-class in one country after another.

The imperialists, tied down by life-and-death struggles in their own countries, could not continue their attacks on Russia without provoking the workers even further, and driving their soldiers to mutiny.

A strike by Hungarian munitions workers in January 1918 spread like wildfire to Vienna, Berlin and throughout Germany, involving over two million workers. Their central demand, echoing the Russian workers’ demand, was peace. In Finland an Independent Workers’ Republic was proclaimed. After months of fighting it was crushed with the help of German troops.

Then, on 4 November 1918, mutiny broke out at the German naval base of Kiel, and ignited the German revolution. Within days every major city was in the hands of the workers’ councils.

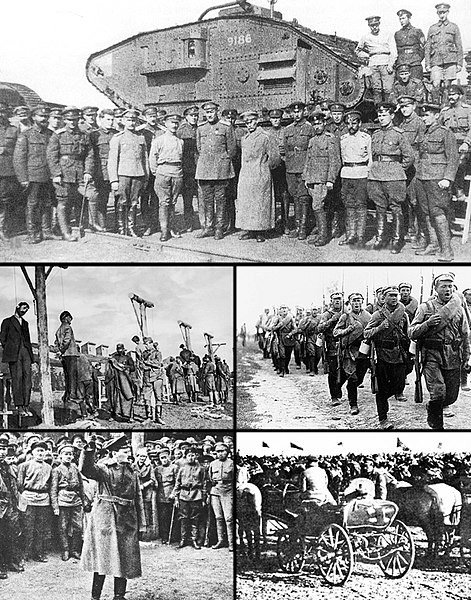

Images of the Civil War / Yanachka

Images of the Civil War / Yanachka

The effect on the Russian working-class was electrifying. The Bolshevik Ilyin-Shenevsky, taking an evening off in a Petrograd theatre, gives a glimpse of its impact throughout the country:

“Before one of the acts was about to begin, a man in jacket and high boots came on to the stage and said: ‘Comrades! We have just had news from Germany. There has been a revolution in Germany. Wilhelm [the emperor] has been overthrown. A Soviet of workers’ deputies has been formed in Berlin and has sent us a telegram of greeting.’

“It is hard to convey what followed… The announcement was met with a kind of roar, and frenzied applause shook the theatre for several minutes…” (The Bolsheviks in Power, pages 127-128)

In Austria, mass strikes and army mutinies finally smashed the imperial Hasburg regime. The empire disintegrated, and in Hungary a revolutionary soviet government took power in March 1919.

France was swept by mass strikes and naval mutiny. British soldiers mutinied, and the Red Flag was hoisted over the Clyde in the Scottish industrial heartland. Ireland was in armed revolt against British rule. Strikes involving four million workers convulsed in the USA in 1919.

These events, hardly mentioned in official history books, demonstrated a law which every socialist needs to understand: a successful workers’ revolution has an incalculable impact internationally, provoking capitalist reaction but, at the same time, inspiring the workers in other countries to come to its defence and follow its example.

The spirit of international solidarity was the Russian workers’ most potent weapon. Not by moral appeals to ‘democracy’ or the ‘conscience’ of the capitalist class, but by linking themselves to the working-class struggle for power internationally, the Bolsheviks won immeasurable support from every corner of the globe, and opened a ‘second front’ in the imperialists’ rear.

Addressed in a comradely way, British and American troops in Russia began to mutiny. On the Black Sea, French sailors hoisted the Red Flag. The imperialists were compelled to withdraw their forces and abandon the Whites to their fate.

The early congresses of the Communist International (see Section 4 below) called on the workers’ movement internationally to take action against any kind of support for the Whites in Russia. In July 1920, following the invasion of Russia by reactionary Polish forces, the Second Congress appealed:

“Stop all work, atop all transport, if you see that despite your protests the capitalist cliques of your countries are preparing a new intervention against Russia. Do not allow a single train, a single ship through to Poland.” (Quoted in J. Degras, The Communist International 1919-1943 ‒ Documents, Volume 1, page 113)

In Britain, the London dockers rallied magnificently to their comrades in Russia when they refused to load the vessel Jolly George with arms for the Whites in Poland.

In July, with the Red Army driving back the invaders, the British government threatened to send troops to Poland. Council of action were set up by trade unionists throughout Britain, threatening a general strike if the intervention went ahead.

The British government ‒ 48 hours after rejecting the Soviet reply to its ultimatum ‒ backed down.

On the battlefields of Russia, as in the international arena, the workers’ victory was only made possible by the Bolsheviks’ uncompromising revolutionary policy.

A soldier, speaking at a mass meeting in Petrograd, makes clear the class program that the Red Army was built on:

“The soldier says: ‘Show me what I am fighting for…Is it the democracy, or is it the capitalist plunderers? If you can prove to me that I am defending the Revolution, then I will go out and fight without capital punishment to force me’.

“When the land belongs to the peasants and the factories to the workers and the power to the Soviets, then we’ll know we have something to fight for, and we’ll fight for it!” (John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World, pages 45-46)

A key factor in the struggle is leadership ‒ in the first place, ideas and program; but following from this, the role of individuals in grasping those ideas, embodying the forward drive of their class, and showing others the way.

It would be impossible, for example, to deny the historic contribution of Marx and Engels in the development of the program of socialism, or of Lenin in preparing the way for the October revolution.

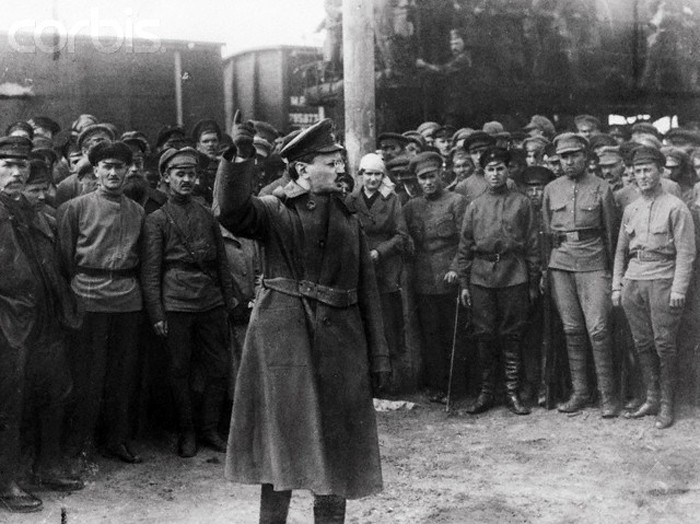

Trotsky addressing Red Guards during the Civil War / Image: fair use

Trotsky addressing Red Guards during the Civil War / Image: fair use

It would be equally impossible to underestimate Trotsky’s role as Commissar for War from 1918 to 1925 in building the Red Army and leading it to victory.

Trotsky organized the Red Army as a revolutionary army, motivated by political understanding, not by blind obedience. His unshakeable confidence in the workers, youth and peasants who made up its ranks is best expressed in his own words:

“What was needed for [saving the revolution]? Very little. The front ranks of the masses had to realize the mortal danger in the situation. The first requisite for success was to hide nothing, our weaknesses least of all; not to trifle with the masses but to call everything by its right name.” (My Life, page 43)

Dedicated young workers were attracted to the army, and became its vanguard. Trotsky continues:

“The Soviets, the party, the trades unions, all devoted themselves to raising new detachments, and sent thousands of communists to the [front]. Most of the youth of the party did not know how to handle arms, but they had the will to win, and that was the most important thing. They put backbone into the soft body of the army.”

The “will to win” was “the most important thing”. How to use arms can be learned in a short time. But the will to win can only be born out of a sense of purpose, a clear goal to fight for, and the understanding of how it can be achieved.

Lenin Trotsky and Kamenev in 1920 / Image: Recuerdos de Pandora

Lenin Trotsky and Kamenev in 1920 / Image: Recuerdos de Pandora

“Until Wrangel took over the remnants of the White Army [i.e., nearly at the end of the war], its officers set an example of drunkenness, looting and violence which their soldiers willingly followed. Outrageous treatment of the local population, the outspoken intention to restore the landlords, and the greater social cleavage between the Whites and the peasantry made the latter finally prefer the Reds.” (Russia 1917 to 1964)

Thus the initial onslaught of the counter-revolution was defeated. The Bolsheviks, however, understood that their victory could bring no more than a respite in the struggle. As Lenin commented in 1920:

“We have now passed from war to peace. But we have not forgotten that war will come again. So long as both capitalism and socialism remain, we cannot live in peace. Either the one or the other in the long run will conquer.” (Quoted by Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, Volume 3, page 365)