We republish the second part of George Collins’ pamphlet (first part available here) on the rise of Stalinism in Russia. Here, he describes how the effect of the Civil War and failure of international revolution demoralised the Russian working-class, isolated the forces of genuine Marxism, and elevated the Soviet bureaucracy.

Setbacks in the International Struggle

In the mighty class movements that followed the October revolution, the overthrow of capitalism throughout Europe was on the agenda.

The victory of the working-class in the developed countries, in turn, would provide a basis for overcoming Russia’s crippling economic backwardness, and remove the threat of imperialist attack.

International organization was essential to unite the workers moving into action in the different countries, and direct the struggle against the worldwide capitalist alliance.

The Second International had ceased to exist as an instrument of the workers’ struggle for power.A new International needed to be built.

The Crisis of Working-class Leadership

Prior to 1914, the Second International was committed to oppose imperialist war by every means, including the general strike. Yet, when war was declared, the vast majority of its leadership came out in active or passive support of their ‘own’ governments.

What were the root causes of this shattering betrayal?

The Second International was formed in 1889 as a federation of (mainly European) social-democratic parties, in general subscribing to Marxism. It was built during a period of imperialist expansion and generally stable growth in the developed capitalist countries. This had a decisive effect on its character.

Important struggles were fought under the banner of the International. Major concessions were won – democratic rights, better wages, better working conditions. A skilled and relatively well-paid ‘aristocracy of labour’ was created in the process. Out of this layer, increasingly, the leadership was drawn, together with intellectuals who decided to build their careers in the labour movement.

Remote from the workers’ daily struggles, these leaders became increasingly comfortable in well-paid jobs as parliamentarians or party and trade union officials. Inevitably their ideas became affected by their surroundings. Their general mood was summed up in the theory of ‘reformism’ put forward by the German social-democrat, E. Bernstein – the idea that capitalism could gradually be ‘reformed’ out of existence through peaceful, parliamentary methods.

This meant that the struggle to overthrow the capitalist state could quietly be pushed into the background. The ‘struggle’ could be led from the soft benches of parliament – at a high salary, paid by the state!

The reformist tendency assumed more and more monstrous proportions. Inevitably, it led to increasing collaboration with the capitalist class. Labour leaders became more and more involved with various organs of the state. Public positions gave them new privileges.

Through all these pressures a nationalist outlook was cultivated. The outlook of the social-democratic leaders was narrowed more and more to the institutions of national and local government. Their links with the international movement were reduced to mere sentiment and phrases.

The catastrophic consequences of this gradual process of political degeneration broke to the surface in August 1914, when the reformists almost unanimously came out on the side of the capitalist state. The workers’ struggle to overthrow capitalism, from this point onward, would be openly and furiously opposed by the reformist leaders.

Lenin at May Day rally in 1919 / Image: Flickr, The Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Library

Lenin at May Day rally in 1919 / Image: Flickr, The Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Library

A historic letter was sent out early in 1919 to the organizations of the revolutionary workers in different countries. It was signed by Lenin and Trotsky on behalf of the Russian Communist Party (the new name of the Bolshevik Party) and by workers’ leaders from other countries. It invited the organizations to a congress to be held in Moscow, and explained the purpose as follows:

“The Congress must establish a common fighting front for the purpose of maintaining permanent coordination and systematic leadership of the movement, a centre of the communist international, subordinating the interests of the movement in each country to the common interest of the international revolution.’ (Quoted in Degras, Volume 1, page 5)

At this congress, held from March 2 to 6, 1919, the Communist (Third) International was formed.

From the “Platform of the Communist International” Adopted at the Founding Conference

“The imperialist system is breaking down. Ferment in the colonies, ferment in the former dependent small nations, insurrections of the proletariat, victorious proletarian revolutions in some countries, dissolution of the imperialist armies…– this is the state of affairs throughout the world today…

“There is only one force that can save [humanity], and that is the proletariat…It must create genuine order, communist order. It must destroy the rule of capital, make war impossible, abolish State frontiers, change the entire world into one cooperative community…

“The growth of the revolutionary movement in all countries, the danger that the alliance of capitalist states will strangle this movement…finally, the absolute necessity of coordination of proletarian action – all this must lead to the foundation of a truly revolutionary, truly proletarian communist international.

“The International…will embody the mutual aid of the proletariat of different countries…[It] will support the exploited colonial peoples in their struggles against imperialism, in order to promote the final downfall of the imperialist world system.”

The inspiring advances by the working-class in 1918-1919, however, marked only the beginning of a drawn-out period of revolution and counter-revolution. In the ebb and flow of class battles flaring up across Europe, the workers were unable to hold on to their early gains.

Two main factors combined to produce a series of defeats: firstly, the deliberate treachery of the social-democratic leaders; secondly, the immaturity of the revolutionary currents in the workers’ movement outside of Russia – in other words, the weakness of genuine Marxist leadership even in the parties of the Third International.

In Germany, large sections of workers still had illusions in the reformist SPD leadership. In November 1918 the reformists, headed by Noske and Scheidemann, were pushed into government as conscious agents of counter-revolution.

Their strategy was to persuade the working-class to accept the authority of the ‘democratic’ capitalist parliament. Then they rebuilt the armed forces of the capitalist state to break up the workers’ councils.

Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, the outstanding revolutionary leaders in the German workers’ movement, were murdered in January 1919 in the military counter-revolution unleashed by their former party comrades.

Rosa Luxemburg was a leading figure in the defeated German Revolution / Image: Rosa Luxemburg-Stiftung

Rosa Luxemburg was a leading figure in the defeated German Revolution / Image: Rosa Luxemburg-Stiftung

But the German capitalists remained weak, and the workers movement was far from crushed. Many more battles would have to be fought before the question of power would be settled for any length of time.

The membership of the Communist International (‘Comintern’) leaped explosively upward. Fifty-one national sections, with a total membership of 2.8 million (only 550,000 in the USSR) were represented at the Third Congress in 1921.

Many different political tendencies were drawn into the International, ranging from ‘centrism’ (i.e. in between Marxism and reformism: revolutionary in words but vacillating in practice) to ultra-leftism.

In Hungary, it was the ultra-left mistakes of the Communist leadership that led to the defeat of the Soviet republic. Refusing to divide the land amongst the peasantry, insisting dogmatically on collectivizing the landlords’ estates, they were unable to win the support of the peasant masses and unify the country.

When counter-revolution struck in the form of an invasion by Romanian and Czechoslovak armies, the peasants were unwilling to fight for a government which refused their most basic demand.

In August 1919, after four months of heroic resistance, the workers’ republic fell. The workers’ movement was subjected to a hideous bloodbath in the reactionary terror that followed.

In Italy, it was the centrist spinelessness of the workers’ ‘revolutionary’ leaders that made victory impossible.

A massive wave of factory occupations in 1920 created a revolutionary situation, with soviets controlling the factories and Red Guards defending them. The capitalist state was paralyzed. The task was to mobilize and arm the workers for the conquest of power.

The ‘Marxist’ leaders of the Italian Socialist Party were forced by pressure from below to profess support for the Comintern. In fact they were divided, and even the ‘maximalist’ (left) wing declined to lead the struggle. The initiative was allowed to pass to the reformists, who in turn handed power back to the capitalists – as usual, in return for some temporary concessions.

In France, in Ireland, in Britain, the Netherlands and many other countries the capitalist class managed to regain control with the assistance of the reformist labour leaders. In every case, this was possible only in the absence of a developed Marxist leadership able to seize the enormous opportunities and isolate the reformists, as the Bolsheviks had done in Russia.

By 1921 the workers’ struggle internationally was in a state of temporary ebb. A peculiar and dangerous correlation of forces was emerging: on the one hand, the capitalist class consolidating its position internationally; on the other hand, the Russian workers’ state isolated and exhausted.

The Exhaustion of Soviet Democracy

The Russian workers’ state survived the civil war, but at a terrible cost.

By 1920, the output of large-scale industry was down to 14 per cent of the 1913 level, and manufacturing output to less than 13 per cent. Agricultural production fell by a further 16 per cent between 1917 and 1921. Steel production stood at 5 per cent of the 1913 level.

Famine raged in east and south-east Russia during 1921 and 1922, killing five million people, reducing isolated communities to barbarism, even to cannibalism. The élan of 1917 was turned into despair, the drive to transform society into a grim struggle for survival.

Political democracy could not survive under these conditions. Every war demands a tight centralization of command over resources and manpower. A revolutionary civil war, moreover, is fought not only on the military front, but also against those sections of society who support the counter-revolution in the rear.

The October revolution had depended on an alliance between the working-class and the peasantry. The peasants had supported the workers’ state because it offered them peace and land.

But the deprivations of the war eroded the peasants’ support for the revolution. Manufactured goods became almost unobtainable, while food supplies were requisitioned from the peasantry to feed the Red Army and the cities.

Only the savagery of the White armies, and their intention of giving back to the landlords, prevented large sections of peasants from going over to the counter-revolution.

Freedom of speech and organization could not be maintained with society split into two and workers’ rule hanging by a thread. Hostile elements, agitating around the grievances of the masses, could have set the country on fire with rebellion and opened the door to counter-revolution. Trotsky explained:

“We are fighting a life-and-death struggle. The press is a weapon not of an abstract society, but of two irreconcilable armed and contending sides. We are destroying the press of the counter-revolution, just as we destroyed its fortified positions, its stores, its communications, and its intelligence system.” (Terrorism and Communism, page 80)

This was the period known as ‘war communism’. In the economy, the consumption of the country’s desperately scarce resources had to be strictly controlled. At the same time, anticipating the victory of the German working-class, the Soviet government hoped to pass from control over distribution to control over production, using the methods of war communism as the starting point for a planned socialist economy.

Reformists and ex-Marxists raised a great outcry at the ruthless measures the Bolsheviks were forced to take in crushing the counter-revolution. What is the difference, they asked, between the methods of Bolshevism and the old dictatorship of the Tsar [emperor]? Trotsky replied:

“You do not understand this, holy men? We shall explain to you. The terror of Tsarism throttled the workers who were fighting for the socialist order. Out Extraordinary Commissions shoot landlords, capitalists and generals who are striving to restore the capitalist order. Do you grasp this…distinction? Yes? For us communists it is quite sufficient.” (Terrorism and Communism, pages 78-79)

Repression, however, was seen by the Bolsheviks as an exceptional and temporary method, forced on them by the imminent danger of reaction. Even under these critical conditions they remained conciliatory towards their political opponents, on condition that they supported the workers’ state in practice, and campaigned for their policies on that basis.

At no stage did the Bolsheviks put forward the idea of a ‘one-party state’, for which there is no foundation in Marxism.

In practice, however, those who supported the revolution overwhelmingly joined the Bolsheviks. The opposition parties were increasingly abandoned to out-and-out enemies of the workers’ state. They struggled, and they lost.

In June 1918 the soviets excluded the Right SRs and Mensheviks from their ranks as a result of their involvement with the counter-revolution.

As late as August 1920 the Mensheviks held their party conference in Moscow, and received press coverage. But by 1921 most of the Menshevik leaders had left Russia, to conduct their campaign against the Soviet state from abroad.

The Communist Party congress of 1921 recognized that workers’ democracy needed to be rebuilt. But the basis for workers’ democracy – the unity, organization and revolutionary energy of the working-class – had been shattered by the superhuman effort of winning the war.

Bolsheviks massacred by Czechoslovak legionaries / Image: Lt. William C Jones

Bolsheviks massacred by Czechoslovak legionaries / Image: Lt. William C Jones

The collapse of industry meant the decimation of the workers’ ranks:

“By 1919 the number of industrial workers declined to 76 percent of the 1917 level…By 1920, the figure for industrial workers generally fell from three million in 1917 to 1,240,000, i.e., to less than half. In two years the working-class population of Petrograd was halved.” (A. Woods and E. Grant, Lenin and Trotsky: What They Really Stood For, page 75)

The workers’ political cadre – the class-conscious activists who had mobilized their workmates, led the strikes, taken up arms, created and led the soviets – was almost eradicated. As Ilyin-Zhenevsky recorded in Petrograd even in the opening days of the war:

“the front was calling for reinforcements – both rank-and-file Red Army and leading executives…the Petrograd Committee sent to the front about 300 such persons, members of our Party. We were having to sacrifice our best forces to the demands of the front.” (The Bolsheviks in Power, pages 116-117)

Thousands of these revolutionary cadres perished in the war. Most of the survivors were absorbed into the ministries of the workers’ state.

The workforce remaining in the factories was transformed into the opposite of the revolutionary vanguard of 1917. As early as 1919 a delegate to the congress of trade unions warned:

“We observe in a large number of industrial centres that the workers…are being absorbed in the peasant mass, and instead of a population of workers we are getting a half peasant or sometimes purely peasant population.” (Quoted by Woods and Grant, page 75)

With the class-conscious workers decimated and dispersed, with the raw, semi-peasant workforce in the factories struggling night and day to continue production with dilapidated equipment and constant shortages, the soviets ceased to function.

The All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which had been supposed to meet every three months, was meeting only once a year by 1918; and even those meetings were insufficiently prepared.

Through utter exhaustion the masses were no longer able to exercise power directly. This factor was decisive in the degeneration of the Russian workers’ state.

But, it might be asked, couldn’t the Bolsheviks have ensured that the state remained an instrument of working-class policy? They were in power – why could they not stamp out bureaucratism and carry out socialist policies?

This question is also important in clarifying why, today, genuine socialist policies are impossible without mass working-class participation in the running of every state organ.

The next three sections will examine in more detail the objective barriers the Bolsheviks were faced with, the limitations of their control over the state apparatus in the absence of functioning soviets, and the effects of the changing situation on the Communist Party itself.

Bureaucracy and the Workers’ State

Lenin, shortly before the October revolution, brilliantly explained the nature of the workers’ state in his book The State and Revolution:

“Alongside of an immense expansion of democracy, which for the first time becomes democracy for the poor…the dictatorship of the proletariat brings about a series of restrictions on the freedom of the oppressors, the exploiters, the capitalists. We must suppress them in order to free humanity from wage slavery; their resistance must be crushed by force…but it is now the suppression of the exploiting minority by the exploited majority. A special apparatus, a special machine for suppression, the ‘state’, is still necessary, but this is already a transitional state.” (see pages 107-110)

The “dying away” or “withering away” of the state as a specialized organ of repression and control, as armed bodies of men separate from the mass of people – this is the political measure of workers’ rule. Lenin sums up what it means:

“The exploiters are naturally unable to suppress the people without a highly complex machine…but the people can suppress the exploiters with a very simple ‘machine’…by the simple organization of the armed masses (such as the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers Deputies…)” (page 110)

How would this “simple machine” work in practice? How can the working people keep control over the state they had created, and prevent the growth of a military and bureaucratic elite? Lenin’s basic guidelines are as valid today as on the day they were written:

- “No official to receive a higher wage than that of the average skilled worker…”

- “Administrative duties were to be rotated amongst the widest strata of the population to prevent the crystallization of an entrenched caste of bureaucrats.”

- “All working people were to bear arms to protect the revolution against threats from any quarter, internal or external.”

- “All power was to be vested in the Soviets. The composition of the Soviets, lay delegates from the workplaces subject to instant recall, obliged delegates to report back to mass meetings of their workmates…and thus ensure maximum mass participation.” (R. Silverman and E. Grant, Bureaucratism or Workers’ Power?, page 3)

The revolution had smashed the old Tsarist state to the extent of driving out the most reactionary generals and nobles at the head of the ministries and the armed forces. Communists took their places wherever possible.

But a thoroughgoing transformation of the state apparatus was impossible with the resources of the isolated Soviet Union. The Bolsheviks numbered only 23,600 in February 1917. A minority of this number formed the cadre of the party, able to lead others in struggling for party policy. The state apparatus, on the other hand, numbered hundreds of thousands of officials.

‘Specialists’ and skilled administrators of the old regime could not be replaced; they had to be kept on, even at the cost of bribing them with privileges. In the town of Vyatka in 1918, for example, no fewer than 4,476 out of 4,766 officials were the same individuals who had previously served the Tsar.

Trotsky, in his book The Revolution Betrayed, explained the significance of what was taking place.

A workers’ state, he said, is “a bridge between the bourgeois [capitalist] and socialist society”. Its task is to create a society of abundance through the planned use of resources, through which class divisions – and the state itself as an organ of class rule – will disappear.

For the first period, the workers’ state has to operate with the economic means it has inherited from capitalism. It has to use the skilled people trained under capitalism and some of the methods of capitalism: the division of labour, the payment of wages, etc.

The whole development of the workers’ state is thus determined by “the changing relations between its bourgeois and socialist tendencies” (page 54) – i.e., between the remaining elements of the old bourgeois apparatus and its methods of control from above, and the development of working-class management from below.

Only the increasing command of the working people over society can eradicate the remnants of capitalism.

In backward Russia, however, the soviets had ceased to exist as organs of the armed people. Day-to-day administration was in the hands of an army of non-Communist officials, representing the outlook of the privileged layers in society.

Politbureau at 14th Conference of the All Union Communist Party / Image: fair use

Politbureau at 14th Conference of the All Union Communist Party / Image: fair use

Bureaucracy in a backward country, Trotsky explained, is a product of backwardness itself – the weakness of the working-class, its lack of skills, and the position of power which the state officials enjoy:

“The basis of bureaucratic rule is the poverty of society in objects of consumption, with the resulting struggle of each against all. When there are enough goods in a store, the purchasers can come when they want to. When there are a few goods, the purchasers are compelled to stand in line. When the lines are very long, it is necessary to appoint a policeman to keep order. Such is the starting point of the Soviet bureaucracy. It ‘knows’ who is to get something and who has to wait.” (The Revolution Betrayed, page 112)

Thus, the bureaucracy in an isolated, backward workers’ state does not simply become redundant and “die away”. To the extent that the “underdeveloped” working-class is unable to take over its functions, bureaucracy acquires – at least for a period – an objective basis for its existence.

Through the bureaucracy, the pressure of the reactionary classes were exerted upon and within the Russian workers’ state. This became more and more obvious as the exhaustion of the soviets left officials with greater freedom to act as they wished.

The political representatives of the working-class, organized in the Communist Party, were caught up in an increasingly hard-fought struggle against this bureaucracy.

Lenin, struck down by illness in the last two years of his life, became sharply aware of the dangers of the situation. At the fourth Comintern congress in 1922 he gave the international delegates this frank appraisal of the position in Russia:

“Undoubtedly, we have done, and will still do, a host of stupid things…Why do we do these foolish things? The reason is clear: firstly, because we are backward country; secondly, because education in our country is at a low level; and thirdly, because we are getting no outside assistance. Not a single civilized country is helping us. On the contrary, they are all working against us. Fourthly, our machinery of state is to blame. We took over the old machinery of state, and that was our misfortune. Very often this machinery operates against us…We now have a vast army of government employees, but lack sufficiently educated forces to exercise real control over them.” (Lenin, The Fourth Congress of the Communist International, page 19)

By “educated forces”, Lenin meant Communist workers, organized and able to control the “specialists”. Lenin could offer no immediate solution to the problem because, within Russia, there was none.

“In all our agitation,” Lenin said, “we must…explain that the misfortune which has fallen upon us is an international misfortune, that there is no way out of it but the international revolution.” (Quoted by Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, volume 3, page 367).

In other words, only the conquest of power by the working-class in the developed countries, and the provision of large-scale technical assistance to their brothers and sisters in Russia, could remove the basis for bureaucratic power.

Party Democracy

The exhaustion of the Soviet working-class placed a critical responsibility on the Communist Party and its leadership to defend the gains of the revolution.

War conditions destroyed the soviets, the basic organs of the workers’ state. By 1921, even the Executive of the Congress of Soviets was meeting only three times a year. ‘Sovnarkom’ (the Council of People’s Commissars, or government) remained as the effective organ of state power.

Sovnarkom consisted of leading Communists, elected to carry out party policy. Naturally they operated within the discipline of the party.

The party remained, in other words, as the nucleus and backbone of the workers’ state. Authority was necessarily concentrated in the hands of the central committee – and, later, the political bureau (‘Politbureau’) elected by the central committee – as a result of the extreme centralization required by the war.

Signing the Treaty of Brest Litowsk / Image: fair use

Signing the Treaty of Brest Litowsk / Image: fair use

Trotsky gave an example of what this meant at the Comintern congress of 1920, in relation to the question of signing peace with Poland:

“Who decided this question? We have Sovnarkom, but it must be subject to a certain control. Whose control? The control of the working-class as a formless chaotic mass? No. The central committee of the party has been called together to discuss the proposal and decide whether to answer it.” (Quoted in E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, page 226)

But the centralization of power under Lenin and Trotsky, however uncompromising, at no stage degenerated into systematic bureaucratic imposition from above.

The party and its cadre had been built through the struggle to unite a large number of separate revolutionary groups, each with its own leadership and ideas, around a Marxist program. The method was that of debate. The right of members or groups (‘factions’ or ‘tendencies’) to question the leadership, and campaign for their ideas in an organized manner, was absolutely taken for granted.

In 1918, for example, the opposition of the ‘Left Communists’ arose out of sharp debates within the party over the question of peace with Germany. For a fortnight they published their own daily paper in Petrograd; in Moscow they won control of the party organization.

But, with the start of the civil war, the Lefts closed ranks with the rest of the party and threw themselves into the struggle.

The explosion of unbridled workers’ democracy during those early days is well captured by the account of Ilyin Zhenevsky:

“A People’s Commissar [Minister]…was obliged in some cases not to issue orders but to address requests to an administrative organ that was subordinate to him. And this own organ might not agree with the People’s Commissar, and might refuse his request. This sort of thing was a common occurrence. A broad democratism in the way affairs were conducted found expression in the slogan ‘power at a local level.’” (The Bolsheviks in Power, page 30).

Even in the Red Army, critics of Trotsky’s leadership – essentially supporters of guerrilla war – were able to organize themselves as a ‘military opposition’ and campaign for their views. They were defeated through argument and example.

In late 1920 there emerged the so-called Workers’ Opposition, with a program summed up by Carr as “a hotchpotch of current discontents, directed in the main against the growing centralization of economic and political controls”. (The Bolshevik Revolution, page 203)

Their views were carried in the party press, day by day, for months on end. A pamphlet stating their case was circulated at the party congress in March 1921, where the issues were to be fully debated.

The proceedings of the congress, however, were dramatically cut across by the uprising of sailors at the naval base of Kronstadt, an island in the Bay of Finland facing Petrograd.

The Kronstadt Uprising

In 1917 the Kronstadt sailors had been in the forefront of the revolution. By 1921 this generation had disappeared to the war fronts and been replaced with peasant conscripts, politically inexperienced, who came under Anarchist influence.

Affected by all the peasants’ grievances, demanding more freedom but without a program for solving the country’s problems, they staged an armed insurrection under the slogan “Down with Bolshevik tyranny!”

This presented a far more serious threat to the workers’ state than the bands of armed insurgents still roaming parts of the country. Kronstadt commanded the approach to Petrograd. With Kronstadt out of government control, Petrograd could not be defended. This gave the Whites and the imperialists a unique opportunity to attack a key centre of the revolution.

Kronstadt sailors in 1917 / Image: Anarkistimatruuseja

Kronstadt sailors in 1917 / Image: Anarkistimatruuseja

The Bay of Finland was still frozen, defended by heavy guns and by the Baltic Fleet, would become impregnable. Time to solve the crisis was very short.

The sailors refused to surrender. Trotsky with the unanimous support of the party leadership, ordered the attack. After days of bitter fighting, Kronstadt was taken by Bolshevik troops.

The survival of the Soviet Union once again hung by a thread. Would the rebellion spread? To delegates at the party congress it was clear that firm and united leadership was essential. Public divisions in the party, at this point, would have been seized upon by the enemy to disorient the workers and peasants. It was decided that organized factions within the party had to be dissolved.

Lenin, a year later, summed up the basis for this unprecedented position:

“If we do not close our eyes to reality we must admit that at the present time the proletarian policy of the party is determined not by the character of its membership, but by the enormous undivided prestige enjoyed by the small group which might be called the Old Guard of the party. A slight conflict within this group would be enough, if not to destroy this prestige, at all events to weaken the group to such a degree as to rob it of its power to determine policy.” (Collected Works volume 33, page 257)

The operative words were “at the present time”. The Bolsheviks knew that problems could not be resolved by organizational measures alone; in the longer run, unity could only be built on discussion, education and agreement. The denial of tendency rights could only be justified as an emergency measure in grappling with the immediate crisis, to be abolished as soon as the situation was once again under control.

The Struggle for Power in the Communist Party

The Kronstadt uprising underlined the explosive resentment that had built up among the peasantry at the sacrifices, shortages and forced requisitions imposed on them during the war years. There was no prospect of an immediate breakthrough by the working-class in the West. Clearly, it was impossible to continue the regime of war communism without risking a generalized insurrection.

Lenin, in a simple example, summed up the situation:

“If we could tomorrow give 100,000 first-class tractors, supply them with benzine, supply them with mechanics…the middle peasant would say: ‘I am for Communism.’ But in order to do this, it is first necessary to conquer the international bourgeoisie, to compel it to give us these tractors.” (Quoted in Woods and Grant, Lenin and Trotsky: What They Really Stood For, page 76)

The tenth party congress of March 1921 could see no alternative to abandoning war communism (first advocated by Trotsky the previous year) and adopting what was called the ‘New Economic Policy’ (NEP) – a series of concessions to the capitalists and richer peasants who dominated agricultural production. It provided them with profit incentives to step up production for the market, as a means of feeding the towns and reviving industry.

The NEP undoubtedly succeeded in restoring a measure of life to the economy. By 1922 industrial output had risen to 25 percent of the 1913 level, though mainly in the branches of light industry supplying the peasants’ demand.

On the other hand, the NEP marked a serious retreat in the workers’ fundamental drive to collectivization and central planning of the economy. It greatly strengthened the so-called ‘NEP-men’ – a breed of middlemen who took advantage of the continuing shortages to speculate and line their own pockets.

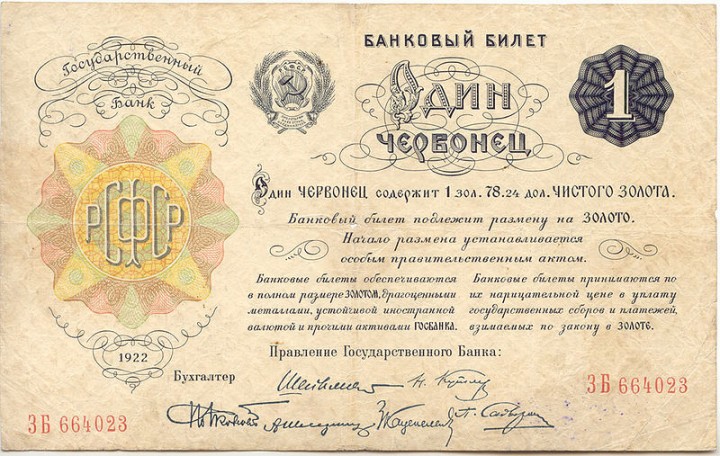

Chervonetz, money bill used under the NEP / Image: fair use

Chervonetz, money bill used under the NEP / Image: fair use

The balance of forces in Russian society was tilting further and further against the working-class. The kulaks and NEP-men shared a position of privilege with the state bureaucracy. These layers were becoming more confident and determined to consolidate their position. Their pressure on the workers’ leaders was increasing.

Victor Serge describes the distortions that were coming into existence:

“Classes were reborn under our very eyes: at the bottom of the scale, the unemployed receiving 24 roubles a month; at the top, the engineer receiving 800; and in between the two, the party functionary with 222, but obtaining a good many things free of charge…There was squalid, heart-breaking poverty…while wealth was arrogant and self-satisfied…The young people drank, old people drank, drunkenness became a plague. And the worst of it was that we could no longer recognize the old party of the revolution.” (From Lenin to Stalin, page 39)

The bureaucracy did not form a class in the Marxist sense (i.e., a social grouping with a necessary function in the productive system). Already it was degenerating into a layer of parasites, exploiting the shortage of skills to extort privileges as of right.

Inevitably, tensions were increasing between the “arrogant, self-satisfied bureaucracy”, entrenched in the state apparatus, and the surviving Bolshevik cadre. The bureaucracy could not rest easy while power remained in the hands of the revolutionary Marxists. A struggle for control over the Communist Party was inherent in the situation.

In the party, the Marxist cadre was stretched to breaking point by the demands of public duties, while the ranks of the party were swelled by a massive influx of new members. Membership increased from 23,600 in February 1917 to 115,000 at the beginning of 1918, 313,000 a year later, and 650,000 in March 1922.

Many of those who joined, especially during the dark days of the civil war, were militant workers and youth attracted to the party of the revolution. But, increasingly, ex-Mensheviks, bureaucrats, NEP-men and other hostile elements, seeking a new vehicle for their political ambitions, began to turn their attention to the Communist Party.

As early as March 1919 the eighth party congress recognized the danger:

“Elements which are not sufficiently communist or even directly parasitic are flowing into the party in a broad stream. The Russian Communist Party is in power, and this inevitably attracts to it, together with the better elements, careerist elements as well…A serious purge is indispensable in the Soviet and party organizations.” (Quoted by Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, page 212)

The inner-party struggle was pushed into the background during the war years. The purge was eventually carried out in 1921-22. Unlike the ruthless bureaucratic attacks on opposition of later years, also known as ‘purges’, it consisted of a careful examination by local party organizations of their members, to decide which of them, through their commitment and activity, could in fact be counted as Communists.

A further decision by the eighth congress resulted in the establishment of a People’s Commissariat of Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection (‘Rabkrin’) in February 1920, with the task of fighting “bureaucratism and corruption in Soviet institutions”.

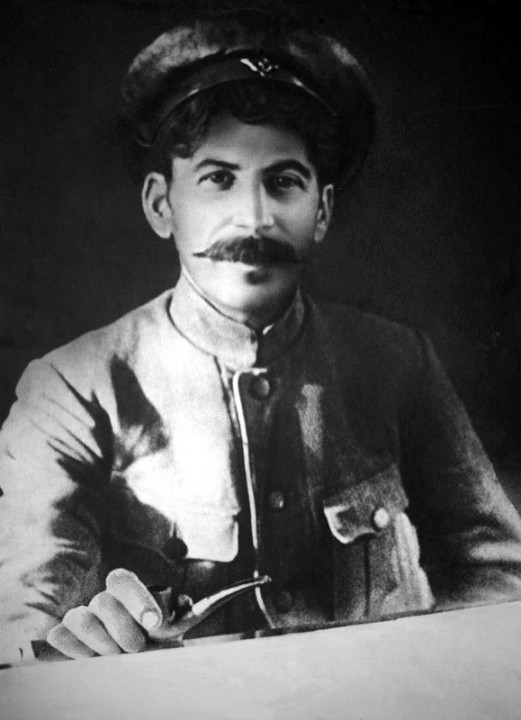

As People’s Commissar in charge of the new department, the congress had appointed Joseph Stalin – a party member of long standing; no theoretician but a good organizer, who was hardly known outside of the party itself. In 1922 Stalin was appointed to another important administrative position: that of general secretary.

Rabkrin failed totally in its task. In practice its members consisted, as Trotsky put it, of “workers who have come to grief in other fields.” Or as Lenin commented: “the best workers have been taken for the front,” (Quoted by Carr, pages 232-233).

But there were more fundamental reasons why the tide of bureaucratic encroachment could not be halted.

Russia’s backwardness was reflected, politically, in the weakness of the proletariat in relation to the peasantry and the reactionary classes, nationally and internationally. As Lenin put it:

“While we continue to be a country of small peasants, there is a more solid basis for capitalism in Russia than for communism.” (Quoted in The Platform of the Joint Opposition, page 6)

The social weakness of the Soviet working-class could not be overcome by administrative measures; bourgeois pressures within the state apparatus could not be eliminated through the creation of new bureaucratic structures. The solution lay in the political regeneration of the working-class through the advance of the revolution internationally.

Joseph Stalin in 1918 / Image: fair use

Joseph Stalin in 1918 / Image: fair use

The influence of the bureaucracy increasingly pervaded the party. Many Communists, absorbed in complicated administrative work, were already being ‘led’ by the bureaucracy.

Even the party leaders were coming under pressure to adapt to the ‘practical’ demands of the bureaucracy, to concentrate on creating stability in Russia through organizational measures, and relegate the international revolution to the background.

Lenin, in his last period of active life, became increasingly aware of the dangers posed by the power of the bureaucracy. At the eleventh party congress in 1922 (the last he attended) he sounded this warning:

“The [state] machine refused to obey the hand that guided it. It was like a car that was going not in the way the driver desired but in a direction someone else desired: as if it were being driven by some lawless, mysterious hand…perhaps of a profiteer, or of a private capitalist, or of both.” (Collected Works, volume 33, page 279)

Stalin came to the fore in this period. It was not his own personality or abilities, or even his conscious intentions, that transformed this colourless individual into the tyrant of later years. Stalin’s rise to power was entirely a consequence of the changing balance of forces in society and the state.

The bureaucracy of the workers’ state was beginning to isolate the ‘socialist tendency’, and to corrupt elements in the workers’ leadership that were politically weak. Stalin was a key official who proved ‘most consistent and reliable’ to the bureaucracy. As Trotsky explains:

“(Stalin) brought (the bureaucracy) all the necessary guarantees: the prestige of an old Bolshevik, a strong character, narrow vision, and close bonds with the political machine…The petty-bourgeois outlook of the new ruling stratum was his own outlook. He profoundly believed that the task of creating socialism was national and administrative in its nature.” (The Revolution Betrayed, pages 93, 97)

The exceptional centralization of power brought about by the civil war was, to the bureaucracy, the natural method of government. It provided the means of protecting their privileges against the threat of future working-class control.

Stalin played a central role in the consolidation of the bureaucracy’s position within the party apparatus. From 1922, he systematically installed his own followers as branch, district and provincial secretaries. This gave him effective control over the day-to-day implementation of policy, the organization of meetings, the election of congress delegates, etc.

These manoeuvres paved the way for a head-on collision with Lenin, Trotsky and the remainder of the Bolshevik leadership.

The Turning Point

1923-1924 marked a turning point in the Soviet Union: a period when the contradictions in the state and the party erupted into a decisive political struggle.

By the end of 1922 Lenin was seriously ill after suffering a series of strokes. It was no longer certain when or if he would return to political activity.

The bureaucracy was hostile and fearful towards Trotsky – next to Lenin the most authoritative and implacable Marxist leader of the party. However, certain ‘old Bolshevik’ leaders – swayed by political narrowness, personal ambitions and loyalties – were also reluctant to see Trotsky, in Lenin’s absence, take his place at the head of the Politbureau.

In December 1922, Zinoviev (then president of the Communist International) and Kamenev (a close associate of Zinoviev) formed a secret faction with Stalin (later known as the ‘trio’ or ‘triumvirate’) for the specific purpose of conspiring against Trotsky. This gave them an effective majority in the six-member Politbureau and, as a result, a commanding authority over the central committee and the party as a whole.

It was Lenin, from his sickbed, who first sensed the significance of what was happening, and opened the struggle against Stalin and the bureaucracy.

In a brief note, later known as his ‘Testament”, Lenin wrote on December 25, 1922: “Comrade Stalin, having become General Secretary, has unlimited authority concentrated in his hands, and I am not sure he will always be capable of using that power with sufficient caution…”

Ten days later he added:

“Stalin is too rude, and this defect, although quite tolerable in our midst in dealing and among us Communists, becomes intolerable in a General Secretary. That is why I suggest that the comrades think about a way of removing Stalin from that post and appointing another man in his stead who in all other respects differs from Comrade Stalin in having only one advantage, that of being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite and considerate to comrades, less capricious, etc. This circumstance may appear to be a negligible detail. But I think that from the standpoint of safeguards against a split…it is not a detail, or it is a trifle which may assume decisive importance” (Collected Works, vol. 36, pg. 594-596).

Lenin did not spell out the “decisive importance” which he feared that Stalin’s behaviour could acquire. But what could it mean except that Stalin, coming into conflict with the best representatives of Marxism in the party, would find himself the tool of hostile forces – the kulaks, the bureaucracy, the ‘capitalists’ and ‘profiteers’?

This insight alone could explain Lenin’s surprising demand that the general secretary be removed so quickly after his appointment.

But with Lenin on his deathbed, Stalin and his faction behaved with increasing arrogance, abusing their powers in defiance of all the traditions of the party.

Matters came to a head with Stalin’s bureaucratic incorporation of the Soviet Republic of Georgia into the USSR (formed on January 30, 1922) and his repression of the local Bolshevik leaders. Lenin, when he found out what had happened, felt that a struggle against this alien tendency in the party could no longer be postponed.

Too ill to attend the twelfth party congress in April 1923, Lenin entrusted Trotsky with the task of defending the Georgian Bolsheviks by delivering a “bombshell” against Stalin.

But Stalin retreated, accepting all Trotsky’s criticisms and correcting his formulations on the national question. Trotsky was reluctant at this point to press home a public attack on Stalin, which would have been seen as a ‘power struggle’ for Lenin’s position, and would have raised the danger of splitting the party.

Final photo of Lenin / Image: fair use

Final photo of Lenin / Image: fair use

Thus, a confrontation was postponed. Shortly afterwards Lenin suffered a further stroke, and was eliminated from political activity until his death in January 1924.

Over the next months the tensions in the party exploded around two central issues: party democracy, and economic policy.

At the congress Trotsky had drawn a balance sheet of the NEP, and pointed out the dangerous lag in industrial production. He used a diagram of price changes of industrial and agricultural products to illustrate his point. It had the appearance of an open pair of scissors: agricultural prices showing a downward line, and industrial prices a rising line.

By March 1923, industrial prices had reached 140 per cent of their 1913 levels, while agricultural prices had dropped to less than 80 per cent. The problem which this reflected was subsequently called the ‘scissors crisis’.

If industrial production continued to decline and prices continued to rise, Trotsky warned, a break between the peasantry and the proletariat, between the countryside and the towns, would become inevitable.

The congress accepted Trotsky’s arguments for a new turn within the framework of the NEP: to develop the state sector on the basis of a central plan, and to expand industry, to eventually absorb and eliminate the private sector.

But this policy change remained a dead letter. The bureaucracy, bound to the ‘private sector’ by ties of common privilege, had no desire to undermine it. In practice they continued as before to rely on the kulaks to increase production for profit.

In July and August there was a wave of strikes as workers vented their frustration against their harsh conditions. The leaders – many of them old Bolsheviks – were arrested on the orders of the bureaucracy. All the signs showed that the sickness in the party was reaching a dangerous level.

Trotsky sounded a warning. Imprisoning opponents, he explained, would solve nothing while the immediate causes of the conflict remained: lack of economic planning, and the hold of the bureaucracy over the party.

“This present regime”, Trotsky wrote to the Central Committee on October 8, “is much further from any workers’ democracy than was the regime under the fiercest period of war communism.” (Documents of the 1923 Opposition, page 2) The hierarchy of secretaries, appointed from above, “created party opinion”, dominated the rank and file workers, and ensured that critical views were given no genuine hearing.

Within days of Trotsky’s protest, a statement was issued by 46 other leading party members, expressing their criticism of the Politbureau’s course and various proposals to correct it.

Victor Serge, a member of the 1923 Opposition, explains the general position:

“The country was approaching an irremediable economic crisis, a crisis which might arouse a hundred and twenty million peasants against the socialist power and place it at the mercy of foreign capital by forcing it to import (on credit? and under what conditions?) great quantities of manufactured goods. To forestall this crisis certain measures had to be taken before it was too late.

“These measures were:

- “To restore democracy in the party, so that the influence of the workers might be felt; to ventilate the State bureaus. This was the obvious condition for the success of all economic measures.”

- “To adopt a plan for industrialization and appreciably rebuild industry within a few years.”

- “In order to obtain the resources necessary for industrialization, force the well-to-do peasants to deliver their wheat to the state.” (From Lenin to Stalin, page 40)

Thus, the lines of the inner-party conflict were being drawn more clearly. It was a struggle between opposing social forces: between a tendency basing itself on the working-class, and one defending the “well-to-do peasants” and other privileged sections.”

The ‘trio’ and their supporters were thrown into turmoil by the challenge. The statement by the 46, against all party precedent, was banned, and Trotsky was condemned for ‘initiating’ it.

But, under pressure from the majority of the party (including the army and the youth), the bureaucracy was forced to retreat. They accepted the demands of the Opposition in words, and proclaimed a ‘New Course’ of freedom and democracy in the party – but keeping all the strings of power in their hands.

Trotsky replied with an Open Letter to party members on December 8, warning that a ‘New Course’ on paper was not enough, that the party could not be turned back onto the road of Bolshevism unless the rank and file – and the youth in particular – acted to “regenerate and renovate the party apparatus”. (The New Course, page 71)

This letter was received with tremendous enthusiasm among the party workers – and by the bureaucracy as a declaration of war. The debate was to be resolved at the thirteenth conference, meeting in January 1924.

The struggle in the Soviet party, however, was decisively cut across by the developments in Germany during 1923.

The Defeat of the German Revolution

Germany’s precarious stability was shattered in January 1923 when French troops occupied the Ruhr industrial area to extract, at gunpoint, the ‘war reparations’ which the German imperialists were being forced to pay as the price of their defeat in the World War.

The German economy slumped. Inflation, already skyrocketing during 1922, became astronomical – probably in the region of 1,000,000,000,000,000 percent during 1922-1923!

The living standards of workers and the middle-class collapsed. The working-class swung sharply to the left. Factory councils sprang up in opposition to the reformist union leaders. The KPD (Communist Party of Germany) grew by tens of thousands. ‘Proletarian hundreds’ (workers’ militias) were formed, involving 60,000 workers by the autumn, with (by capitalist estimates) 11,000 rifles in their hands.

In two states, Saxony and Thuringia, left-wing SPD governments were in power, relying on KPD support.

On August 11 a general strike brought down the right-wing Cuno government in Berlin. Germany was in a revolutionary crisis.

The workers’ leadership was unprepared. The KPD leadership was divided between the ‘centre’, ‘left’ and ‘right’ factions, with the cautious Brandler at its head. Hesitation and uncertainty marked its policy throughout.

The Comintern was increasingly affected by the struggle in the Soviet party. The conservatism and short-sightedness of the bureaucracy, transmitted through the leadership of the Soviet party, was beginning to prevail.

The Comintern representative in Germany, Radek, gave his full backing to Brandler. As late as July Stalin advised that “the Germans should be restrained and not spurred on”. (Carr, The Interregnum 1923-1924, page 195)

Only with the fall of the Cuno government did the Executive Committee of the Comintern (ECCI) accept Trotsky’s argument that a struggle for power was on the agenda in Germany, that political and organizational preparations for armed insurrection urgently needed to be made.

KPD propaganda poster / Image: Flickr IISG

KPD propaganda poster / Image: Flickr IISG

But tragically, this policy was not followed through. Trotsky sums up what happened:

“Why didn’t the German revolution lead to a victory? The reasons for it are all to be sought in the tactics, and not in the existing conditions. Here we had a classical example of a missed revolutionary situation. After all the German proletariat had gone through in recent years, it could be led to a decisive struggle only if it were convinced that this time the question would be decisively resolved and that the Communist Party was ready for the struggle and capable of achieving the victory. But the Communist Party executed the turn [to insurrection] very irresolutely and after a very long delay. Not only the Rights but also the Lefts…viewed rather fatalistically the process of revolutionary development up to September-October 1923.” (The Third International After Lenin, page 70)

The triumvirate was incapable of intervening and instilling a bold revolutionary understanding of the situation in the KPD leadership. Trotsky was deliberately isolated. The consequences were disastrous. As a close co-worker of Trotsky wrote in 1936 (quoted in Ted Grant, The Rise and Fall of the Third International, page 28):

“When the German bourgeoisie at last gathered its forces, proclaimed a state of siege, proceeded to take the offensive, the [KPD] capitulated without a struggle” – that is, they called off the insurrection. (Word of the capitulation did not reach Hamburg in time, and an isolated uprising took place, which was crushed after days of fighting.)

The failure of the KPD leadership cost the German working-class, and the European revolution, the chance of a victory that would have changed the course of world history. Instead, the KPD was declared illegal for some months. With massive US aid, the German economy was stabilized and capitalism pulled back from the brink.

A few months earlier the mass Bulgarian Communist Party after its leaders, dogmatically, refused to enter a united from with the Peasant Union government against a right-wing military coup. Also in Poland the workers, inspired into action by the German events, were defeated.

These setbacks had a critical effect on the inner-party struggle in Russia. Germany in particular had always been seen as the key to the European revolution. Now it became clear that no relief could be expected from Western Europe in the months or years ahead.

A vicious cycle was set in motion. The increasing grip of the bureaucracy on the Soviet party (and through it, on the Comintern) was becoming a serious obstacle to the development of revolutionary policies and leadership internationally. The setbacks resulting from this, in turn strengthened the currents of demoralization and conservatism which the bureaucracy thrived on.

Less politicized workers began to lose confidence in the Marxist perspective of international revolution. To backward layers, the scepticism and cynicism of the bureaucracy began to look ‘realistic’.

“A wave of depression passed over Russia,” Serge wrote, “and the bureaucracy had its own way for three years.” (From Lenin to Stalin, page 42)