The African National Congress (ANC) is holding its 54th National conference – at the Nasrec Expo Centre near Gold Reef City from 16 to 20 December – more divided than ever before. Tottering on the brink, the party has never been in such a lamentable state, not even in the days of the underground and in exile.

It is now openly split between two bourgeois factions. The outcome is expected to be very tight and, after years of turmoil, the stakes are extremely high. The divisions are so deep that it could even lead to a breakdown of the conference – and at some point even the collapse of the organisation. The effects of this will be far-reaching.

For the first time there are seven candidates who are competing for the position of president to replace Jacob Zuma. This, however, is not a sign of growing “internal democracy” as some diehard apologists would like to suggest. The litany of court cases within its ranks in the run-up to the Nasrec conference is another indicator of internal fragmentation.

In reality there are two frontrunners, Cyril Ramaphosa and Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. Both are representatives of rival bourgeois factions – Ramaphosa, one of the richest men in the country, represents the big bourgeoisie, while among the backers of Dlamini-Zuma there are the upstart black bourgeoisie around the Gupta family. Whoever wins the contest will therefore not serve the interests of the workers but those of one or other bourgeois faction.

The conference and the fate of the ANC is bound to have a profound effect on all classes in society. The particular development of the class struggle and the development of political forces in South Africa historically, means that the ruling class does not have a second party with mass support. This makes the fate of the ANC all the more important, especially if the ANC splits, which is highly likely, in particular if the Ramaphosa faction loses. Even if Ramaphosa wins, especially with a small majority, the conference could lead to further upheaval and splits. The Zuma faction would almost certainly embark on a scorched earth approach. This is because the whole network, which is based on corruption and patronage, could unravel. The whole political system would be destabilised, leading to all kind of convulsions.

It is still possible, however, that the two sides could strike some sort of deal at some stage but this would solve nothing fundamental, as the deep economic crisis and the rising anger within society would soon undermine such a deal. In any event, the period after the the Nasrec conference will be turbulent. Just Like the Polokwane conference ten years ago, the effects of the Nasrec conference will be felt for years.

The Polokwane conference

Jacob Zuma became the president of the ANC at the 2007 conference in Polokwane. This conference was a turning point in the ANC. Its impact on the class struggle and the political situation in South Africa has lasted until today. Here, the left wing of the ANC together with its allies in the labour federation, COSATU and the Communist Party, defeated the right-wing administration of Thabo Mbeki after a revolt in the ranks of the Alliance. The conference brought to the fore the tensions between the working class base and the ruling elite of the ANC. It graphically illustrated the social distance between the ruling elite around Mbeki and the ranks of the movement and how much the pressure from the bourgeoisie was determining the policies and conduct of these leaders. In other words, it was a contest between two opposing class forces – the ruling class and the working class.

But ten years later all the euphoria of the left-wing victory at Polokwane is gone. Instead of a contest involving a left wing, now the party is in the midst of a titanic battle between two bourgeois factions, neither of which will serve the interests of the working class.

In defence of Polokwane

Nowadays it has become fashionable, especially in the capitalist media, to pour dirt over the events in the run-up to the 2007 conference. For them the Polokwane conference was merely a form of thuggery. This is the usual label these people place on events which are driven by ordinary working class people.

However, even those who had participated in the left-wing campaign have now distanced themselves from it. The argument made nowadays is that Polokwane was a “mistake” and that however “bad” the right liberal Thabo Mbeki was, Jacob Zuma has turned out to so much worse. This argument has two sources: on the one hand those leaders who subsequently broke with the ANC and moved to the left of it and, on the other hand, those who are now trying to hide the role they played in facilitating the rightward drift of the ANC subsequent to Polokwane – such as the SACP.

However, the main source of the crisis in the ANC does not lie with the process leading up to Polokwane or even with the conference itself, but with the mistaken policies and approach of the left wing after the Polokwane victory. The Polokwane coalition of the SACP, COSATU and the ANC Youth League took the fight to Mbeki and eventually defeated him, installing Jacob Zuma as ANC president as a candidate of the left. As opposed to the “aloof” Mbeki, Zuma presented himself as a “common man” who would be more “amenable” to the aspirations of the masses. However, his programme just like Mbeki’s, was based on working within the confines of capitalism. It did not aim to make any fundamental change in society.

The Polokwane revolt

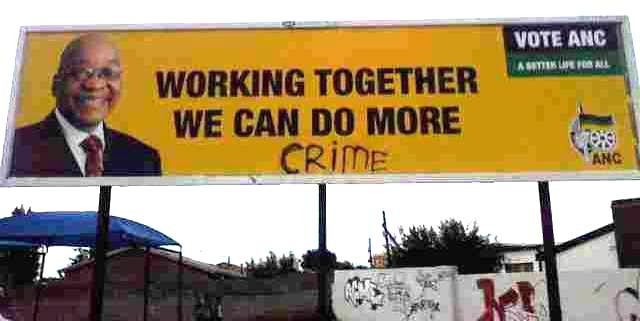

Zuma has always been surrounded by personal scandals and controversy – even in the apartheid days of exile and underground work. This continued when the ANC became the governing party. In 2002 news broke that Zuma had been implicated in the massive arms deal corruption scandal through the Schabir Shaik investigation. Shaik was eventually convicted of fraud and sentenced to jail in 2005. Zuma has subsequently been locked in a legal marathon for ten years to fight off being prosecuted on 783 counts of corruption, fraud, money laundering and racketeering. In 2005 Mbeki fired Zuma as Deputy President of the country allegedly for his corrupt relationship with Shaik, opening a huge fight between the two most powerful men in the ANC.

Zuma has always been surrounded by personal scandals and controversy – even in the apartheid days of exile and underground work. This continued when the ANC became the governing party. In 2002 news broke that Zuma had been implicated in the massive arms deal corruption scandal through the Schabir Shaik investigation. Shaik was eventually convicted of fraud and sentenced to jail in 2005. Zuma has subsequently been locked in a legal marathon for ten years to fight off being prosecuted on 783 counts of corruption, fraud, money laundering and racketeering. In 2005 Mbeki fired Zuma as Deputy President of the country allegedly for his corrupt relationship with Shaik, opening a huge fight between the two most powerful men in the ANC.

All of this coincided with the revolt against Mbeki’s policies at branch-level of the ANC. As far back as 1996 Mbeki started to implement the Growth Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) macro-economic policy which was developed by the Finance Ministry, the Development Bank of Southern Africa, the South African Reserve Bank and representatives from the World Bank. The policy led to a reduction in social spending, including in healthcare and education, cuts in the civil service, deregulation of markets, allowing prices and the exchange rates to be determined through market forces, large-scale privatisation, “wage moderation”, “cost containment measures” like water and electricity cut-offs for non-payment, etc.

This led to a rising class struggle which found an expression through the SACP and COSATU, which had not been part of Mbeki’s designs. The clashes between the two factions intensified and go as far back as the 2002 Stellenbosch conference, when Mbeki launched a campaign against the SACP and Cosatu, calling them “ultra-left” and stating that the ANC would be better off without them.

Under the rising pressure from below, a left wing developed among the ANC Youth League, the SACP, and the COSATU unions. All these processes converged in the period between 2005 and 2007. On top of years of right-wing drift the working masses were directly intervening in the traditional organisations to change their direction. With the aim of self-preservation, personal ambition and self-enrichment, Zuma demagogically put himself at the head of the movement. This was the basis of the removing of the liberal leadership of Thabo Mbeki at the Polokwane conference in December 2007.

The capitalist policies carried out by the ANC and the militant response from the workers resulted in the former mass liberation movement beginning to fragment and split along class lines. The ANC split to the right in 2009 when a section of the liberals broke away to form the Congress of the People (COPE). However, this soon fell flat because the pendulum within the working class was swinging to the left.

The 2008 collapse and the rising class struggle

The Polokwane conference took place on the eve of the global financial crisis which hit South Africa in late 2008 when global credit tightened and commodity prices fell sharply. The economy contracted by 1.8 percent in the final quarter of 2008 and by 6.4 percent in the first three months of 2009 and entered into recession for the first time in two decades. The effects of the slowdown in the economy were felt immediately. Output in the mining sector contracted by a record 33 percent in the last quarter of 2008. The manufacturing sector contracted by 22 percent. Consumer spending fell by almost 5 percent, its biggest contraction for 13 years. Company failures rose by 47 percent in the first four months of 2009 and household debt rose sharply. The effect of all of this was immediately felt by the working class in the form of more than one million job losses. In reality, more than a decade after the end of Apartheid, none of the main problems of the South African masses had been solved. That was the basis of the Polokwane revolt and the class struggle which ensued.

Mass strike – March 2012

Mass strike – March 2012

The blows against the working class did not have the effect of cowering them. On the contrary, in the wake of the Polokwane conference, the workers gained confidence and were spurred onto the offensive. With the left wing at the head of the workers’ movement, the Polokwane victory opened the path for a huge upsurge in the class struggle as the workers pushed for their demands and fought back against the effects of the crisis. After the 2009 national elections there was an unprecedented rise in strikes, demonstrations and protests.

In 2010 a massive strike wave swept across the country. In April of that year the municipal workers went on a countrywide strike, affecting several cities and metropolitan areas. In May the transport workers went out on strike, winning a 15 percent wage increase. Also in May, workers at the Passenger Rail Industry won a 16 percent wage increase after taking strike action. In July and August alone 1.3 million public sector workers brought the whole country to a standstill. In 2010 the number of working days lost to strikes was the highest on record at that time. Approximately 161,852,721 working hours were lost to strikes compared to 11,525,815 of 2009, according to the Labour Department.

At the same time ideas such as nationalisation of the commanding heights of industry and the SACP’s “Socialism in our lifetime” slogan became popular rallying cries throughout the country. But while the masses were pushing the Alliance to the left in order to solve their acute problems, the new leadership under Zuma was not moving in the same direction. The left wing which had taken over the ANC had no plans of breaking with capitalism or the South African bourgeois state. Thus it was bound to follow the dictates of capital, and the Zuma leadership came under huge pressure from the bourgeoisie to put a halt to the leftward drift of the ANC.

The right turn of the SACP

In the context of the crisis of capitalism, the working class was going onto the offensive, but the leaders of the ANC left wing – that is, the leaders of the SACP – did not push for “socialism in our lifetime”, but deliberately betrayed the whole process. Instead, they joined the government in 2009 , which was adopting capitalist policies, to provide it with a left cover. Having achieved their narrow aim of removing Mbeki, the SACP leaders, then started attacking the left wing of the Alliance. At each step they placed themselves in opposition to the growing movement on the streets and on the shop floors. In 2011, Blade Nzimande, the General Secretary of the party, started attacking the Youth League’s call for nationalisation from his cosy ministerial post, calling it “rescuing BEE deals that are in debt”. Even if this were true, the party could have easily solved this by putting itself at the head of the call for nationalisation and demanded that it should happen without compensation.

The SACP became Zuma’s biggest defender against criticism from the left wing of the Alliance. The way they defended Zuma during the Nkandla corruption scandal will go down as infamy. Not even the murder of mine workers at Marikana was enough for these so-called “Communist” leaders to drop their support for Zuma. They continued to do this while faithfully implementing capitalist policies as ministers in the government. In fact, the SACP leaders became a key motor force in the rightward drift of the ANC and helped to consolidate Zuma’s hold on the party.The adoption of a genuine socialist programme was never the intention of the “Communist” party leaders.

Julius Malema speaking to striking minersThese attacks eventually contributed to the split of COSATU, the breaking up of the leading bodies of the ANC Youth League, and the expulsion of Julius Malema and Floyd Shivambu.

Julius Malema speaking to striking minersThese attacks eventually contributed to the split of COSATU, the breaking up of the leading bodies of the ANC Youth League, and the expulsion of Julius Malema and Floyd Shivambu.

Particularly disgraceful was the role the SACP leaders played in the split in the trade union movement and the expulsion of NUMSA from COSATU, which opened the way for the weakening of the trade union movement as a bulwark against the capitalists in and outside of the ANC. As a result today, COSATU is being turned into a toothless organisation with its leaders moving to the right and endorsing Ramaphosa, the big business representative, as ANC presidential candidate.

Marikana

A qualitative change in the class struggle then opened up. The sharp rise in the class struggle in this period reshaped the whole political landscape and the militancy of the workers transformed the political situation. With the leadership of the ANC and the SACP not responding to their demands, the workers went on the offensive on the industrial front. Between 2009 and 2013 the number of strikes reached even higher levels than at stages in the late 1980s when the masses were fighting against the apartheid state. The number of community protests over basic services such as water and electricity provision more than doubled between 2007 and 2014. Intelligence service company Municipal IQ recently showed that South Africa had almost one protest every second day in 2014 with Gauteng being the most protest-ridden province. Furthermore, by January 2013 the data shows that service delivery protests in 2012 accounted for 30 percent of protests recorded since 2004. Between 2008 and 2013 approximately 3000 protests took place.

It was in this period that the mine workers embarked on the most significant strike wave in decades. This necessity expressed itself through an accident: the bosses inadvertently provoked the strikes by colluding with the leadership of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) to play off the workers against each other at Impala Platinum. In January 2012 Impala gave a wage increase to only one category of workers, excluding others. Those who were excluded went on a wildcat strike for about six weeks and completely shut down production. Eventually, Impala was forced to give up and concede to the workers’ demands, leading to a victory for the workers as a whole at the company.

However, all of this took place outside of the normal collective bargaining timelines which convinced workers in other mines to also demand wage increases outside of the formal bargaining processes. Soon a massive strike wave swept across the big mines, including Lonmin, Aquarius, Impala, Anglo American Platinum, Royal Bafokeng Platinum, Xstrata, AngloGold Ashanti, Gold Fields, Gold One, Harmony, Kumba Iron Ore and Samancor.

However, all of this took place outside of the normal collective bargaining timelines which convinced workers in other mines to also demand wage increases outside of the formal bargaining processes. Soon a massive strike wave swept across the big mines, including Lonmin, Aquarius, Impala, Anglo American Platinum, Royal Bafokeng Platinum, Xstrata, AngloGold Ashanti, Gold Fields, Gold One, Harmony, Kumba Iron Ore and Samancor.

This militancy put the government on the spot. The workers at Lonmin’s Marikana mine still massively supported the ANC. The vast majority were members of the NUM, which is part of the Alliance. But while the workers were protesting against their low pay and squalid conditions, the ANC government, under the influence of Cyril Ramaphosa who sat on the board of Lonmin, responded with brutal violence. On 16 August 2012 the police shot dead 34 striking workers at Marikana. This was a qualitative turning point in the history of the class struggle. Here, the government, which the workers up till then had viewed as “their” government, in similar fashion to the old Apartheid regime, was prepared to murder striking black workers to protect the interests of the capitalists.

The workers responded immediately with a massive strike wave that would last more than 90 days. Almost all Lonmin’s 28,000 workers went on strike. Anglo American Platinum, the world’s largest producer, had to suspend operations due to the strikes in Rustenburg.The strikes moved from the platinum mines to the gold industry. With tens of thousands of workers on strike, none of the mines of Anglogold Ashanti were operating. Gold Fields had 23,500 of its 35,700 workers on strike. Harmony Gold Kusasalethu mines were also shut down due to the strike wave. The whip of counter-revolution was spurring hundreds of thousands of workers into struggle, and class consciousness was rising fast.

Splits

Julius MalemaThe Marikana massacre was a turning point in the whole situation. It emphatically showed that under capitalism the state always serves the interests of the capitalists. The divisions which opened up as a result of the rising class struggle after the Polokwane conference grew into big splits in the Alliance. This process was reflected in the ANC Youth League under Julius Malema which began to gain traction by calling for the nationalisation of the mines and for the implementation of the Freedom Charter which calls for the nationalisation of the monopoly industries. Whatever weaknesses the Youth League and its leadership might have had is secondary to the fact that their stance was influenced by the pressure of the upsurge of the class struggle.

Julius MalemaThe Marikana massacre was a turning point in the whole situation. It emphatically showed that under capitalism the state always serves the interests of the capitalists. The divisions which opened up as a result of the rising class struggle after the Polokwane conference grew into big splits in the Alliance. This process was reflected in the ANC Youth League under Julius Malema which began to gain traction by calling for the nationalisation of the mines and for the implementation of the Freedom Charter which calls for the nationalisation of the monopoly industries. Whatever weaknesses the Youth League and its leadership might have had is secondary to the fact that their stance was influenced by the pressure of the upsurge of the class struggle.

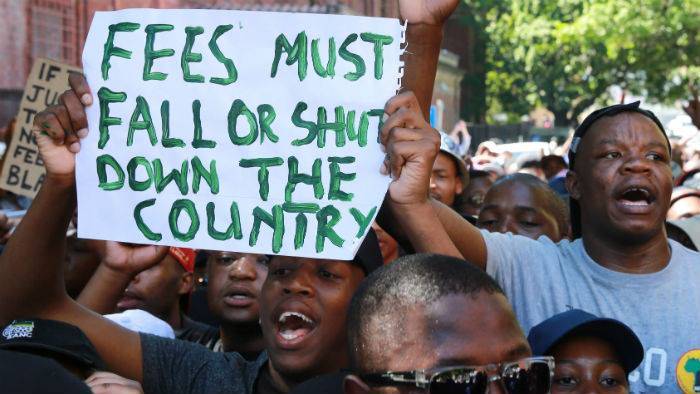

The ANC-led Alliance was openly split to the right and to the left. The biggest development in this period on the trade union front was the split in COSATU and the mass split away of the country’s biggest union, NUMSA. The move by the SACP to join the government on a pro-capitalist basis meant that there was now a massive vacuum to the left of the ANC. A part of the mass protest movement was now taking place outside of the ruling ANC-led alliance. It was this vacuum which allowed Julius Malema and Floyd Shivambu to form the Economic Freedom Fighters. The formation of the new labour federation, SAFTU and the mass student protests over the last two years are further manifestations of this.

Further to the right

Having removed the Mbeki leadership, the Polokwane coalition completely unravelled. After clearing out the Alliance of large parts of its left wing, the Mangaung conference in 2012 paved the way for a further strengthening of the right wing after the left failed to put forward a challenge in an ill conceived bid for “unity”. At the Mangaung conference Zuma consolidated his grip on the party and pushed it further to the right. The subsequent purging of the Youth League was aimed at silencing the critical voice of the youth.

Through his access to the state, Zuma became the focal point of a growing wing of the bourgeoisie, led by the reactionary Gupta family, which was making its wealth on the basis of looting and plundering the state. Meanwhile, having been spent to hold the masses at bay, this faction is now disposing of the SACP like a used rag. The SACP leaders are desperately trying to remain by swinging from left to right. The Alliance now exists in name only and is heading for a formal breakup.

Beyond Nasrec

The fierce class struggle over the last decade has transformed the political situation fundamentally. The advanced layers of the workers and youth which spearheaded the Polokwane revolt, like NUMSA and the leadership of the ANC Youth League, are now outside of the ANC. In 2007 the ANC had a parliamentary majority of nearly 70 percent. Now it runs the risk of losing its majority altogether in the 2019 elections. The fact that the small rural province of Mpumalanga will send the second largest contingent of delegates to the conference shows how its support has fallen in the urban areas. Already it had lost control of some of the biggest metropolitan areas in the country in the 2016 local government elections and the clearing out of the advanced layers of the working class and the youth opened up the space for capitalist elements to come to the fore in the ANC. This has created the situation where the leadership contest at Narec will be between capitalist factions.

Since at least the 1950s the African National Congress has held a near monopoly of support from the black working masses. Now 23 years after it won the 1994 elections, the former liberation movement is facing an unprecedented crisis. The collapse of its moral authority after ten years of corruption scandals and attacks on the working class has plunged it into its deepest crisis ever. This reflects the class contradictions within the party. While the ANC leadership has joined the ranks of the ruling class, living lavish and luxurious lives, the conditions of the working masses, for whom the party was their traditional political vehicle, have either stagnated or worsened. The crisis in the party reveals that the interests of these two forces cannot be reconciled. These class contradictions are tearing the party apart. The problem is that there is not a genuine revolutionary party in South Africa which could lead the working class and the oppressed out of this quagmire. The building of such a revolutionary tendency is the most urgent task facing the working class and the revolutionary youth of South Africa today.