Trotsky warned in 1940 that the attempt to solve the ‘Jewish problem’ in Europe through the dispossession of the Palestinians would be a “bloody trap”. These words ring true to this very day. But the real history of Israel-Palestine has been buried under mountains of falsification.

In this article, Francesco Merli explains the shady dealings and machinations of the imperialist nations that paved the way for the partitioning of historic Palestine. This episode in history attests to the short-sightedness of the ruling class, who opened up a Pandora’s box of violence and degradation that has plagued the land ever since.

The article traces this history from the origins of Zionism, through the creation of Israel, the Six Day War, the first Intifada, up to the betrayal of the Oslo Accords in 1993.

Over the past one-hundred years, the Middle East has been the chessboard for many decisive games between the imperialist powers. The reason for the relevance of the region, considered of relatively secondary importance until the end of the 19th century, is well known: beneath the lands of the Middle East lie the planet’s main oil reserves. Palestine, for a number of geo-political and historical reasons, has increasingly become the focus of Middle Eastern tensions.

The long drawn-out process of decomposition of the Ottoman Empire suddenly accelerated with the ‘Young Turk’ Revolution of July 1908, but was completed only after the Empire’s defeat in the First World War.

Already, the Empire had lost control over part of its European provinces in the course of the 19th century. Over that period Britain and France had also seized control over large parts of North Africa. France took over Algeria in 1830 and occupied Tunisia in 1881. Britain invaded Egypt and Sudan in 1882. Even a secondary power such as Italy took a slice of the Empire by occupying Libya in 1911.

The government of the Young Turks entered the War alongside the Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary. Long before the end of the War Britain and France had already reached an understanding on how to share among themselves the spoils of the Empire.

Accustomed to dominating vast colonial empires, the British and French agreed on creating a series of states artificially separated by borders arbitrarily drawn with a ruler on geographical maps. The deal was sealed by the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement (with the consent of Russia and Italy) in January 1916.

The deal was denounced and published by the Bolsheviks in November 1917, immediately after the Revolution, to the dismay of the imperialists. However, after the War, the partition happened along the lines agreed upon by Sykes and Picot. France took control over Syria and Lebanon. Britain was recognised a mandate over Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), Palestine and a protectorate over the puppet monarchy of Transjordan (now Jordan).

The British imperialists had cynically raised the hopes of the Arab nationalists for an Arab homeland. A negotiation along these lines was established by Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner to Egypt, in his correspondence to Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, in exchange for Arab support in the War. The Arab insurgence against the Ottomans played a key role in the demise of the Ottoman Empire.

However, the British imperialists had no intention of honouring their promises and were more interested in expanding their own sphere of influence. The rise of Arab national consciousness represented a strategic threat to their imperialist interests.

The Jewish question and Zionism

The history of Jewish immigration to Palestine is closely woven with the rise of the Zionist movement at the end of the 19th century. Until then, the indigenous Jewish population living in Palestine amounted to a few thousand people, mostly concentrated in the urban areas.

A turning point came with the wave of pogroms unleashed in the Russian empire by the secret police against the Jewish minority, held responsible for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881.

Angry mobs whipped up by hired provocateurs stormed Jewish neighbourhoods, looting them and assaulting the population. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were driven out of Russia and the Ukraine to escape the terror campaign of killings, beatings, rapes, lynchings and the destruction of their livelihood and properties.

More waves of pogroms followed in 1903-6, and an even bigger one in 1917 and 1921, unleashed by the White armies during the civil war against the Bolshevik revolution.

At the end of the 19th century another episode sent enormous shockwaves. In 1894-95 Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish officer, was wrongfully convicted for treason. His trial unleashed a wave of anti-Semitism in France.

The “Dreyfus affair” played an important role in the conversion to Zionism of a cosmopolitan Jewish bourgeois intellectual, Theodor Herzl (1860-1904). In fact, Herzl wrote The Jewish State, what would become the political manifesto of Zionism, in the aftermath of the trial.

The “Dreyfus affair” played an important role in the conversion to Zionism of a cosmopolitan Jewish bourgeois intellectual, Theodor Herzl / Image: public domain

The “Dreyfus affair” played an important role in the conversion to Zionism of a cosmopolitan Jewish bourgeois intellectual, Theodor Herzl / Image: public domain

Herzl became the main organiser and theoretician of the Zionist movement, and developed it as an international force. He devised the tactics of organising mass emigration of Jews from Europe to Palestine.

He also came to the conclusion that the growth of anti-Semitic tendencies in Europe was to be regarded as a potential help for the Zionist project, a means of putting pressure on what he regarded as secular Jewish inertia.

Hence, the Zionist political project was based on the effort to lobby European heads of state and ministers (often fervently anti-Semitic) in the attempt to persuade them that the emigration of Jews to Palestine represented a golden opportunity to rid themselves of the Jewish problem, as well as the fact that a Jewish state in Palestine could be useful to the great powers as an “outpost of European civilisation against Asian barbarism”.

From the very beginning the Zionist project had to rely on the patronage of one of the main imperialist powers as a guarantee for its success.

Herzl publicly reassured the Ottoman authorities that Jewish immigration would only materially benefit the Empire, in order to ensure the necessary compliance of the Ottoman authorities. However, in private he recognised that there could be no Jewish state without the expropriation and expulsion of the Palestinians.

“We must expropriate gently. […] We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our country. […] Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.” Herzl noted in his diary in 1895 (quoted in B. Morris, Righteous Victims).

The realisation of the Zionist reactionary utopia converted Palestine into a battleground and would cost the Palestinians (but also the Jewish settlers) unspeakable suffering. Its reactionary consequences last to the present day.

The Zionist movement at the beginning of the 20th century, however, still represented only a tiny minority, confined to a small circle of Jewish bourgeois and petty-bourgeois intellectuals and patrons.

The development of Arab national consciousness

A constant cause of concern for the Zionist leadership was that Arab workers would organise against their exploitation. Another fear was that the development of an Arab national consciousness would unify the Arabs in resisting Zionist colonisation.

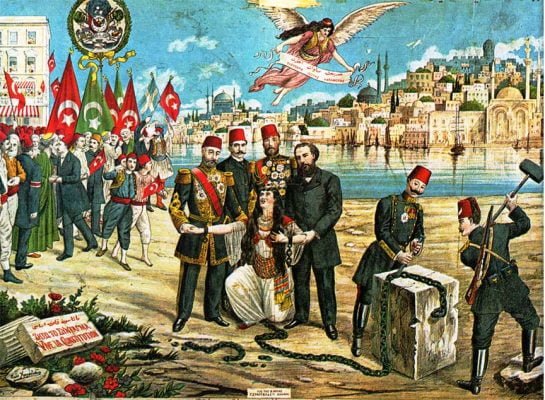

The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 raised hopes of emancipation for all the peoples across the Ottoman empire / Image: public domain

The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 raised hopes of emancipation for all the peoples across the Ottoman empire / Image: public domain

Arab national consciousness started developing in the 1880s. The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 raised hopes of emancipation for all the peoples across the Ottoman empire.

The rapid turn of the new regime towards Turkish nationalism accelerated the mass process of precipitation of national consciousness among all the peoples of the Empire, particularly among the Arabs, who shared a territory spanning from the modern Iraq to Morocco, a common language and tradition.

In Palestine such a process became even sharper due to the growing hostility towards the consequences of Jewish immigration. Every land acquisition by the settlers entailed the automatic expulsion of the Palestinian farmers, often unaware that the official absentee owners of the land had sold it to the newcomers, enticed by the rising price of the land.

According to the historian Benny Morris, the average land price jumped from 5.3 Palestinian pounds per dunam in 1929 to 23.3 in 1935. The price of land in 1944 amounted to 50 times that of 1910.

The settlers did not speak Arabic, nor were they familiar with local culture and traditions, and in many cases did not care to learn them, violating long established customs, common lands, pastures, and above all, access to water. It wasn’t long before the Palestinians felt a growing sense of looming threat from the continuous influx of settlers.

The Balfour Declaration

The strategists of British imperialism became interested. They understood that the Zionist project could become a useful tool to pursue Britain’s plans for the Middle East after the demise of the Ottoman Empire.

On a capitalist basis, the so-called “solution” to the age-old oppression of the Jews, necessarily led to the deflagration of the “Palestinian question” / Image: public domain

On a capitalist basis, the so-called “solution” to the age-old oppression of the Jews, necessarily led to the deflagration of the “Palestinian question” / Image: public domain

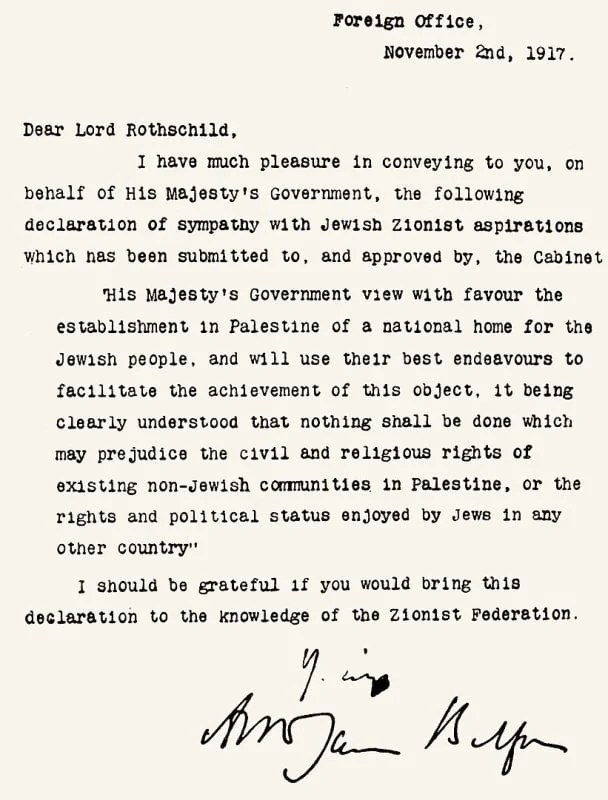

On 2nd November 1917, this shift was summed up in the letter addressed on behalf of the British government by Lord Balfour to Lord Rothschild and the Zionist Federation. The declaration states:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the right and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The subordinate clause clearly showed that even at the time, the British imperialists had an evident understanding of the implications of their endorsement. On a capitalist basis, the so-called “solution” to the age-old oppression of the Jews, necessarily led to the deflagration of the “Palestinian question”.

In 1923, a right-wing Zionist, Vladimir Jabotinsky, wrote his political manifesto, The Iron Wall. He recognised the importance of the Balfour declaration, and argued that the Palestinians had to be forced into submission with an “iron wall of Jewish bayonets” and, he added, “British bayonets”. In his view, the viability of the Zionist project relied on the active support and patronage of British imperialism.

Such support became a reality after the collapse of the Ottoman empire and the establishment of the British mandate over Palestine.

Under British rule, the Zionists were allowed to develop the institutions of a semi-state: the Jewish Agency as an embryonic government; the Jewish National Fund as a way to channel finances and buy land, and most importantly, a Jewish Militia – the Haganah.

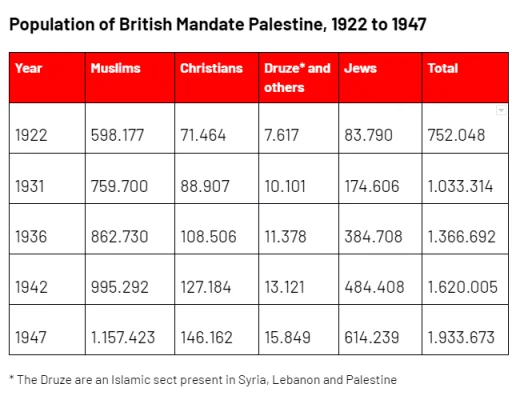

However, at the outbreak of the First World War, there were still no more than 60,000 Jews in Palestine, while the land purchased up to 1908 corresponded to only 1.5 percent of the available land. In the 1920s – as a result of the British Mandate over Palestine – the flow of new settlers accelerated.

In 1929, the overall balance of Jewish emigration since 1880 was as follows: out of about 4 million Jews who emigrated in that period from Central and Eastern Europe, only 120,000 went to Palestine (some of these only temporarily), compared to 2.9 million to the United States, 210,000 to Britain, 180,000 to Argentina, 125,000 to Canada. The settler Jewish population in Palestine was growing, having reached 150,000 in 1929, and rising to over 400,000 by 1936.

The increasing frictions between Palestinians and settlers culminated with the Jaffa riots of May 1921, with dozens of people killed on both sides.

At the outbreak of the First World War, there were still no more than 60,000 Jews in Palestine / Image: fair use

At the outbreak of the First World War, there were still no more than 60,000 Jews in Palestine / Image: fair use

In August 1929, an uprising of the Palestinians against the British occupation turned bloody, with a series of attacks launched against Jewish communities. One of these attacks hit the small Palestinian Jewish community of Hebron (about 600 people), a community dating back to the 16th century.

As a result of the attack, 66 Jews were killed, in spite of the attempt by many Palestinians to protect those fleeing by hosting them in their homes. The Jewish community in Hebron was wiped out. The Haganah repelled other attacks. However, tragically, the death toll of the “bloody days” of August 1929 was 133 Jews and 116 Palestinians.

This gave a decisive impulse to the consolidation of the Jewish militia, the Haganah, increasingly in collaboration with the British occupier.

The formation of the Palestinian Communist Party

During the 1920s and 1930s, opportunities did arise for the building of a revolutionary alternative, based on the working class, which could have avoided the outbreak of a civil war in which Jewish and Arab workers would have everything to lose.

In the early 1920s, the presence of the British colonial administration fostered a certain degree of industrial development of the coastal strip, helping to create an economic sector where Jewish and Palestinian workers worked side by side. This development had an impact on the predominantly rural Palestinian economy and led to intense immigration from the countryside to the coastal cities.

Around the colonial administration arose the railways, the telephone company, the post office and telegraph, ports and shipyards, civil administrations to which were added the local administrations of the cities with a mixed population, and also in the private sector some large companies with foreign capital employed Jewish and Palestinian labour. For example, the Nesher cement factory, the terminal of the Iraqi Oil Company and the refinery in Haifa, and the rapidly expanding building industry.

Between the 1922 and 1931 census, the Palestinian Arab population had grown by 40% and in cities like Jaffa and Haifa by 63% and 87% respectively. The newcomers swelled the ranks of the proletariat in every sector, quickly fuelling a remarkable surge of trade union struggles. Immigration from the countryside was joined by immigration from neighbouring countries, especially Egypt.

The lack of Jewish workforce to replace Arab labour very often led to importing cheap Jewish labourers into Palestine from Yemen or the Maghreb. They constituted a section of the Jewish working class that was particularly exploited and distant from the majority of the Zionists of European origin, who mostly spoke Yiddish and occupied all the leading positions in the Zionist institutions.

It was in this period that the growing divide between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews (descendants of the diaspora of Spanish Jews who settled in the Ottoman empire) arose, which still characterises Israeli society today.

The Sephardim expressed themselves in Ladino, a dialect derived from Spanish. They were often able to speak or understand Arabic and occupied a social rung slightly above the mass of the Arab proletariat. Under these conditions, class consciousness quickly arose among this layer, who instinctively felt closer to the Arabs than to the big Jewish tycoons like Rothschild and company.

The Zionist “socialist” parties, however, bitterly opposed any demand to open the Jewish workers’ unions to the Arab workers.

The differences ranged from David Ben-Gurion’s Hadut Haavoda, who were in favour of the unionisation of the Arabs but in separate organisations of “equal dignity” (under Zionist leadership), and that of Hayyim Arlosoff’s Hapoel Hatzair, who defended the exclusively Jewish character of the trade union organisation in order to promote an increasing division of labour between a Jewish labour aristocracy with the most skilled and best paid jobs and a mass of unorganised Arab manual labourers.

A third position was expressed by another party of the Zionist left, the Po’aley Tziyon. This party shifted to semi-revolutionary positions by seeking membership of the Communist International (CI) in 1924, though not fully renouncing Zionism. The CI refused to accept a party that was not completely freed from Zionism. This led to a split and the founding of the Palestinian Communist Party (PCP). The new party was immediately expelled from the Zionist trade union Histadrut.

Workers’ struggles and class unity

The PCP defended a position in favour of united trade unions, without discrimination along national or religious lines. By pursuing this political line, the PCP was able to take advantage of the growing militancy and the demand for unity arising from the workers’ experience. Such instinct towards unity, however, was opposed and hindered by both the Zionist leadership and the Arab nationalists.

The PCP grew roots among both the Arab and the Jewish working class / Image: public domain

The PCP grew roots among both the Arab and the Jewish working class / Image: public domain

The PCP grew roots among both the Arab and the Jewish working class. The party published two newspapers in two languages. Despite having its main base of support among the Arab workers, the PCP won 8% of the vote in the elections for the Yishuv (the Jewish Council), over 10% if one considers the vote in the cities.

One episode – limited but significant – showed the potential for the development of class unity during a strike. Two-hundred Jewish workers at the Nesher cement factory in Haifa were joined in a strike by 80 Egyptian co-workers, putting forward their own demands, with the latter having reduced rights and being paid half as much.

After a two-month-long strike, the boss conceded some of the Jewish workers’ demands. The deal was voted down by them, 170 to 30 (defying their own union’s position) and they vowed to continue the strike until the demands of their Egyptian comrades were fully met.

The danger that such an example could become contagious prompted the Histadrut leadership to put pressure on the British colonial administration, which clamped down by deporting all 80 Egyptian workers.

A propensity for workers’ unity in the struggle emerged several times in the decade 1925-35. We should mention the bakers’ strike, the struggles of the Haifa port workers and the railway workers, the strike of the public transport and taxi drivers in 1931. In 1935 we see the important struggle of the workers of the Iraqi Oil Company and the Haifa refinery.

During those years, the PCP organised trade unions independently from the Histadrut and gained important bases of support in many areas among the majority of Arab workers, and many Jewish workers. Their successes forced the Zionists to change tactics and promote Arab trade unions federated with the Zionist ones, to counter the influence of the Communists.

The enormous potential represented by the growth of the PCP, however, was wasted by the consequences of the Stalinist degeneration of the USSR. The Soviet bureaucracy under Stalin converted the Communist International into a mere tool to pursue its diplomatic interests. This meant abandoning the correct revolutionary policy of class unity, by pandering towards Arab nationalism during the Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936-39, resulting in the loss of most of the PCP support among Jewish workers.

During the Second World War the PCP suffered an even bigger blow by Moscow’s u-turn in favour of war collaboration with British imperialism, which undermined the party’s base among the Palestinian working class, before receiving a death blow in 1948 by the USSR’s decision to support the formation of Israel.

The reactionary role of the Palestinian elite

Among the Palestinians, the emerging nationalist camp was hegemonized by the elite families, which had supplied municipal officials, judges, police officers, religious officials, and civil servants to the Ottoman administration and later to the British colonial authority. They emerged as the Palestinians’ national leadership. A vast gulf, however, separated the elite from the largely poor and illiterate masses.

The struggle for supremacy between the Husayni and the Nashashibi clans, in the mid-1930s, led to the formation of two rival Arab nationalist parties. The Nashashibi-led National Defence Party was countered by the more extremely nationalist Palestine Arab Party. However, the Husayni and the Nashashibi’s allegiance to Arab nationalism did not prevent both from populating the long list of those who had secretly sold land to the Zionists.

The Palestine Arab Party radicalised its positions along anti-Semitic lines. Many Arab nationalists (including the future Egyptian president Anwar Sadat) openly sympathised with fascism and Nazism. Amin al-Husayni’s words of support for Hitler in a speech to the German Consul in Jerusalem are emblematic: “the Muslims inside and outside Palestine welcome the new regime of Germany and hope for the extension of the fascist anti-democratic, governmental system to other countries.”

Armed Arab nationalist groups developed. The “Black Hand”, led by Sheikh Izz al-Din al-Qassam, carried out sparse attacks against Jewish settlers since 1931. Al-Qassam was killed by British forces in an ambush on 21st November 1935, thus becoming a rallying figure for Arab nationalism.

The pace of Jewish immigration had further increased in the course of the 1930s. Between 1931 and 1934, a prolonged drought hit Palestine. In 1932, agricultural production plummeted by between 30 and 75 percent, depending on the crops and areas affected. This impoverished Palestinian villages and caused overcrowding in the slums around Jaffa and Haifa.

A financial crisis also hit Palestine, caused by the repercussions of the Abyssinian situation, which led to the bankruptcy of many companies. The combination of these factors exacerbated the position of the Palestinian masses.

The Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936-39

The clashes of 1921 and 1929, although violent and bloody, had only directly affected a small layer of the Arab and Jewish population.

The traditional leaders were reluctant to clash head-on with the British authorities / Image: public domain

The traditional leaders were reluctant to clash head-on with the British authorities / Image: public domain

In April 1936, however, the Palestinian revolt spread on a mass basis from the cities, where “National Committees” were spontaneously formed on the initiative of radicalised youth, the shababs. The traditional leaders were reluctant to clash head-on with the British authorities. It was not until 25th April that the Arab Higher Committee was formed to lead the revolt under the leadership of the Husayni.

The Revolt was characterised by a six-month-long Arab general strike and a permanent semi-insurrectionary struggle and armed guerrilla in the countryside (from mid-May to mid-October).

The different scale of this revolt was noted by Ben-Gurion himself, who wrote that the Arabs were “fighting against dispossession… The Arab is fighting a war that cannot be ignored. He goes out on strike, he is killed, he makes great sacrifices.” He also stated on May 19, 1936: [the Arabs] “see… exactly the opposite of what we see. It doesn’t matter whether or not their view is correct… They see immigration on a giant scale… they see the Jews fortifying themselves economically… They see the best lands passing into our hands. They see England identify with Zionism.”

The Zionists (the Histadrut trade union at the forefront) pursued an aggressive strike-breaking policy aimed at replacing Palestinian with Jewish labourers on a company-by-company basis.

In 1937, the secretary of the trade union federation in Jaffa, explained the Zionists’ position thus: “The Histadrut’s fundamental aim is ‘the conquest of labor.’… No matter how many Arabs are unemployed, they have no right to take any job which a possible immigrant might occupy. No Arab has the right to work in Jewish undertakings. If Arabs can be displaced in other work, too… that is good.” (Quoted in Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p. 122.)

For months, the British authorities had no other alternative than waiting for the strength of the insurrection to wane. It was only on 7th September that martial law was proclaimed and a curfew imposed. 20,000 soldiers were shipped in from Britain and Egypt, aided by 2,700 additional Jewish policemen. A counter-insurgency operation began, which prompted the Arab leaders to call off the strike by 10th October, hoping it would lead to a negotiated way out.

The British government convened a Royal Commission led by Lord Peel, to carry out an inquiry and determine the terms for a settlement of the Palestinian-Zionist conflict. The 404-page-long Peel Report, published on 7th July 1937, recommended the partition of Palestine: 20 percent of the territory to the Jewish Authority; Jerusalem and a corridor to Jaffa under British administration, as well as the coastal cities with a mixed population; the rest would be joining Transjordan and form a single Arab state. Corollary to the proposal was the forced transfer of 225,000 Palestinians and 1,250 Jews.

The Zionist leaders Weizmann and Ben-Gurion regarded the Peel Report as a stepping stone to further expansion. Weizmann commented: “The Jews would be fools not to accept it, even if [the land they were allocated] were the size of a tablecloth.” The report was therefore accepted by the Zionists, while it was rejected by the Arab Higher Committee.

Second phase of the Revolt

In September 1937 the Revolt resumed with vigour, but the Arab Higher Committee was torn apart by a violent feud that arose from the Husayni’s attempt to assassinate the leader of the opposing clan, in July 1937. “Streams of blood are now dividing the two factions,” noted Elias Sasson, a senior official of the Jewish Agency, in April 1939.

The insurrection continued in a spiral of clashes and repression. The Arab Higher Committee was outlawed and 200 of its leaders were arrested, many of them hanged, while others flew.

The “Peel Report” spurred the Jewish right-wing revisionist party (those demanding a revision of the British Mandate) to launch a terrorist campaign against ordinary Palestinians. Multiple bomb attacks by the Irgun Zwai Leumi hit Palestinian civilians at bus stations and markets, killing and maiming hundreds.

The Palestinian armed groups acted without a centralised command. Many of them, without perspectives, unfortunately turned into criminal gangs who plundered the Palestinian peasants, quickly alienating their support. This situation decisively undermined the prospects of the Revolt.

The Revolt continued until May 1939, involving at its peak, in the autumn of 1938, about 20,000 Palestinian fighters. On the eve of the Second World War, what had been the most serious and protracted Arab revolt against British occupation ended with a death toll of many thousands and a de facto defeat.

The Second World War and the Holocaust

The defeat of the Revolt sanctioned a sharp turn in British imperialism’s policy. The British feared a new outbreak of Arab revolt when forces had to be made available for other fronts. Moreover, British imperialism did not want to antagonise the Arab bourgeoisie, in an attempt to prevent their collaboration with the Nazis.

The White Paper drafted by the colonial administration (published on 17th May 1939) introduced for the first time a cap on Jewish immigration (a maximum limit of 75,000 over the following five years) and severe restrictions on the purchase of land by Jews. It also set the prospect within ten years of the creation of an independent state governed according to the majority principle.

This change of course did not gain British imperialism more Arab support. However it did undermine Britain’s close relationship with the Zionist leadership. The British u-turn (at the very moment when fears of the Nazi anti-Semitic policy were rising) was experienced as a betrayal by the Zionists.

The Zionist leadership used the desperation of the Jews fleeing Europe to strengthen international support for Zionism / Image: public domain

The Zionist leadership used the desperation of the Jews fleeing Europe to strengthen international support for Zionism / Image: public domain

The British authorities had helped the Haganah’s transition towards “aggressive defence” against the Palestinians. In May 1938, the Haganah set up “field companies” to apply counterinsurgency tactics in the countryside. One month later, Special Night Squads were created, with the task of terrorising during the night Arab neighbourhoods and villages that were supporting the Revolt.

These same tactics would be used on a much higher scale a decade later by the Zionists, to ensure Palestinians fled their villages and homes in terror, in the run-up to the establishment of Israel.

At the beginning of 1939, three secret units known as Pe’luot meyuchadot (“special operations”) were created with the task of carrying out reprisals against Arab villages and guerrilla units, but also of carrying out attacks on British installations and eliminating informers. These units were put under the direct command of David Ben-Gurion.

The first reports of mass deportations of Jews by the Nazis began to filter through, along with the Jewish European refugees, producing a huge psychological impact on the Jewish population of the diaspora (especially in the US) who found intolerable the odious restrictions imposed by the British authorities on immigration.

The attitude of the Zionist leadership towards the Nazi threat, however, was characterised by cynicism. In December 1938, a month after the Nazi pogrom later known as Kristallnacht, Ben-Gurion stated: “If I knew it was possible to save all the [Jewish] children of Germany by their transfer to England and only half of them by transferring them to Eretz-Yisrael, I would choose the latter—because we are faced not only with the accounting of these children but also with the historical accounting of the Jewish People.”

In December 1942, he again commented: “The catastrophe of European Jewry is not, in a direct manner, my business…” (Quoted in Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p. 162).

The Zionist leadership used the desperation of the Jews fleeing Europe to strengthen international support for Zionism and blatantly defy the blockade on immigration imposed by the British authorities, who were determined to clamp down on illegal immigration at all costs.

Part of the Zionist right-wing, however, rejected any collaboration with the British. In November 1944, the Lohamei Herut Israel (LEHI), “Fighters for the Freedom of Israel” (also known as the Stern gang) assassinated in Cairo the British minister resident in the Middle East, Lord Moyne.

A series of boats filled with refugees were set up in open defiance of the British prohibition, provoking a tug-of-war with the Mandate authorities who had decided to block all attempts and deport thousands of refugees to concentration camps on Mauritius and Cyprus. The refugees were pawns, trapped in a cynical power game which led to multiple tragedies.

In November 1940, the Haganah blew up the Patria, a ship anchored in Haifa loaded with 1,700 immigrants awaiting deportation to Mauritius, causing 252 deaths. Another ship, the Struma, with 769 refugees on board, sank on 25th February 1942 in the Black Sea after the British authorities had vetoed their transfer (all-but one were killed).

Very few Jewish refugees escaped to Palestine during the War, while the Nazis were exterminating six million Jews in Europe, along with millions of Slavs, Roma, communists and anti-fascists of different nationality, religion and political orientation.

Well before the proclamation of the State of Israel (14 May 1948), the Zionist dream of forming a state that would protect the Jews by breathing new life into the biblical land of Israel had only produced a nightmare.

“A land without a people for a people without a land” – the slogan adopted in various forms by Zionist propaganda – was a mystification of the real situation of Palestine, removing from the picture the inconvenient presence of the Palestinians.

The Zionist leadership, however, understood all too well that a conflict with the Arab majority for control over Palestine was inevitable. David Ben-Gurion, the first leader of the new-born state of Israel said, as early as 1919, at a meeting of a Zionist leading body:

“Everybody sees a difficulty in the question of relations between Arabs and Jews. But not everybody sees that there is no solution to this question. No solution! There is a gulf, and nothing can bridge it… I do not know what Arab will agree that Palestine should belong to the Jews… We, as a nation, want this country to be ours; the Arabs, as a nation, want this country to be theirs.” (Quoted in B. Morris, Righteous Victims, p. 91).

The new state was founded at the cost of having to base itself on the systematic suppression and oppression of the Palestinian people / Image: public domain

The new state was founded at the cost of having to base itself on the systematic suppression and oppression of the Palestinian people / Image: public domain

In the eyes of the Zionist leaders, every settler who set foot in Palestine represented one more soldier in the war for the conquest of the land. Their every action was aimed at creating the conditions that would allow them to drive the majority of the Arab population out of Palestine and bring about the birth of the Israeli state.

“The attempt to solve the Jewish question through the migration of Jews to Palestine can now be seen for what it is, a tragic mockery of the Jewish people,” Leon Trotsky wrote in July 1940, referring to the about-face of British imperialism, which first favoured Jewish immigration, only to attempt to stop it violently when it no longer suited their interests.

Trotsky pointed out that any solution of the Jewish question on the basis of a rotten capitalist system would become a bloody trap for hundreds of thousands of Jews. Trotsky could not live to see how the War would end and how the balance of forces emerging from it would affect the prospects for Zionism. In the new balance of forces emerging from the War, however, what seemed to be unlikely became possible, and then it became a reality.

Israel was established on the ruins of the British Mandate. However, it was born dripping Palestinian blood, requiring the displacement of 750,000 Palestinians from their land. The new state was founded at the cost of having to base itself on the systematic suppression and oppression of the Palestinian people. The Zionist project was revealed to be a reactionary utopia fraught with tragic consequences. Its implementation inflicted wounds that are still open, more than seven decades later.

Ever since its foundation, Israel’s history has been punctuated by wars. This began with the so-called War of Independence of 1948-49, and the Nakba (catastrophe). This was followed by the Suez War of 1956; the Six Day War of 1967; the Yom Kippur War of 1973, as well as three invasions of Lebanon, in 1978, 1982 and 2006, the countless bombings and skirmishes during the decades-long war of attrition with Hezbollah in South Lebanon, and half a dozen ‘wars’ (meaning mostly heavy bombing campaigns from a distance), against Hamas in Gaza.

The history of Israel has also been characterised by countless movements expressing the Palestinian resistance, including mass insurrectionary movements (the first Intifada in 1987-1992 and the second Intifada in 2000-2003) by the never-tamed population of the Territories occupied in 1967.

Rather than a ‘safe haven’ for the Jews, the concrete reality of the ‘promised land’ turned out to be that of a fortress under siege, surrounded by hostile peoples and enemies. The Israeli ruling class skilfully exploited these wars to entrench a deeply rooted siege mentality among the majority of the Jewish people within Israel and Israel’s supporters in the Jewish diaspora.

Zionist terrorism and British withdrawal

During the War, most Zionists and Arab nationalists had collaborated with the British army. A Jewish brigade of 23,000 men fought under Allied command. The Palestinian contingent amounted to 9,000 men.

In 1944, the land acquired by the Zionists in Palestine still amounted to not more than 6.6 percent of the territory of the British Mandate. However, Zionism had emerged considerably strengthened from the war. The Jewish Agency had in fact become, at least in embryonic form, a semi-state, endowed with its own separate economy, its own institutions and above all, its own army with thousands trained and armed by the Allies during the war.

The most severe among these Zionist terrorist attacks dealt a death blow to the very heart of the Mandate’s administration / Image: public domain

The most severe among these Zionist terrorist attacks dealt a death blow to the very heart of the Mandate’s administration / Image: public domain

Once the war was over, the Zionist leaders changed tactics. Between 1945 and 1948, Haganah and Irgun Zwai Leumi (the armed militia of the Zionist right) joined forces in attacks against the British occupation and the Arab population.

The most severe among these Zionist terrorist attacks dealt a death blow to the very heart of the Mandate’s administration. On 22 July 1946, the Irgun, under the command of the future Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, planted enough explosives to blow up the south wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, where the headquarters of the civil administration of the British Mandate were based. 91 Britons, Palestinians and Jews were killed in the explosion and dozens were injured.

This sudden escalation made the situation untenable for British imperialism. Britain, although victorious in the Second World War, came out of it debilitated, with the Empire in tatters. In April 1947, therefore, the United Kingdom announced its disengagement from Palestine within a year.

This sparked debate over the status of Palestine. The barycentre of imperialist power had shifted decisively in favour of the world’s rising power, the United States. They correctly interpreted the British position as a sign of weakness by an overstretched and creaking empire, and started wielding the Jewish-Palestinian conflict as a cudgel to deal blows against the former ally’s influence in the Middle East.

UN Resolution 181 was passed on 29 November 1947 as a result of US pressure. The UN plan can be summarised as the partition of Palestine into three zones: an Arab state (encompassing an area of 11,500 square kilometres for 804,000 Palestinians and 10,000 Jews); a Jewish state (14,000 square kilometres for 558,000 Jews and 405,000 Palestinians); and an area (Jerusalem), to be placed under international control.

This plan was cloaked in utopianism, considering that the two states would have had to join a Palestinian Economic Union and share currency, resources and infrastructure (ports, post office, railways, roads), as if a no-holds-barred war between Zionists and Palestinians had not been going on for over two decades.

Zionist offensive

With the British occupiers on their way out, the Zionist leadership realised they had a window of opportunity to fill in the vacuum and determine the conditions for partition according to their own terms.

At the end of 1947, Haganah, Irgun and Stern Gang, now joint in a united effort, unleashed a campaign of terror with a series of coordinated attacks on Palestinian villages with dozens of civilian casualties. The attacks increased in intensity in the first months of 1948. Tannoura, Tireh, Saasa, Haifa, Hfar Husseinia, Sarafand, with hundreds of Palestinian victims.

On 9 April, the population of the village of Deir Yassin, near Jerusalem, was massacred by the Irgun. The Red Cross found 254 men, women and children slaughtered. Some of them had been mutilated and thrown into their wells. Begin publicly boasted of the massacre.

The cynical calculation by the Zionist leaders was to conquer as much land on the ground as they could and to make the return of the Palestinian population impossible / Image: Government Press Office Israel

The cynical calculation by the Zionist leaders was to conquer as much land on the ground as they could and to make the return of the Palestinian population impossible / Image: Government Press Office Israel

As a result of the terror campaign, magnified by threats and rumours spread by the Zionists, hundreds of thousands of unarmed Palestinians fled their homes, which were later razed to the ground to make their return impossible. Palestinian refugees rose from 60,000 to 350,000 in a single month.

Zionist terrorism then focused on the cities: on 22 April, Haifa was attacked in the middle of the night, leaving 50 dead and 200 wounded. Another 100 were killed and hundreds injured in a Zionist attack on a column of Palestinian women and children trying to flee.

How does one explain such ferocity? The cynical calculation by the Zionist leaders was to conquer as much land on the ground as they could and to make the return of the Palestinian population impossible: to scare, indeed terrorise, and force the Palestinians to flee and raze their homes to the ground. This, in order to impose a partition of Palestine more favourable to the future state of Israel.

The state of Israel was proclaimed on 14th May 1948. All the main Zionist leaders had been involved in massacres and large-scale terrorism. In this respect there are no differences between the Zionist Left and the Right.

Moshe Dayan, Golda Meir, David Ben-Gurion, Menachem Begin, and many others, the younger Ariel Sharon, Yitzhak Shamir and Yitzhak Rabin – the main leaders of the future state of Israel – learned from their concrete experience the extent to which it is the power relations established with steel and fire on the ground that determine the framework of possible scenarios in the field of international diplomacy. This lesson, they would assimilate and apply systematically in the following decades.

Nakba

Immediately on 15 May, Egyptian, Iraqi, Syrian, Lebanese and Transjordan armies entered Palestine, achieving some military successes in the first phase. A truce was proposed by the UN in June and accepted by both sides, but it only helped the Zionists to organise and rearm.

The counter-attack of the Zionist army after 8 July broke the resistance of the Arab forces, poorly coordinated and often placed under the leadership of British officers. The leaders of the Arab regimes had never abandoned attempts to secretly reach a deal with the Zionists to further their own interests. Abdallah, King of Transjordan, met several times with Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan, to negotiate the annexation of the West Bank to his kingdom (this was achieved in December 1948), while the Egyptians occupied the Gaza Strip.

The Zionist leaders were determined to sweep away all obstacles. The UN envoy, Count Folke Bernadotte, ordered Israel on 13 September to readmit the refugees and rebuild their homes. Four days later he was assassinated by the Stern Gang together with his assistant, the French Colonel Serot.

The Rhodes Armistice of 1949 sanctioned the Arab defeat, ending what the Israelis would consider their ‘War of Independence’. Once again, a history written by the victors denied and attempted to remove from the official records any references to the massacres and atrocities committed.

For the Palestinians, 1948 would instead be the year of the Nakba, the catastrophe, a defeat that would throw the Palestinian masses into a state of deep prostration for over twenty years.

Refugee question and the ‘Israeli Arabs’

Out of a total of 750,000 Palestinian refugees, 39 percent had fled to the West Bank; a further 10 percent ended up in Jordan; 26 percent fled to the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip, which saw its population double in a matter of weeks; 14 percent fled to Lebanon from northern Palestine and 10 percent crossed the Golan into Syria. Only a few (1 percent of the total) escaped to Egypt.

Most of the 1948 Palestinian refugees and their descendants have no citizenship rights in the countries that are hosting them / Image: public domain

Most of the 1948 Palestinian refugees and their descendants have no citizenship rights in the countries that are hosting them / Image: public domain

Almost all of the refugees were herded into huge ‘temporary’ camps on the outskirts of cities, in conditions of total destitution. In such conditions they and their descendants have remained until today in spite of an eightfold increase in the refugee population.

In 1950, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA) was set up. Since then, according to UNRWA’s official figures, the total number of registered refugees from the 1948 displacement, and their children – three generations down the line – has reached the staggering figure of 5.9 million, and this figure does not take into account the refugees of the 1967 Six Day War.

Several generations have only known these camps and conditions. Most of the 1948 Palestinian refugees and their descendants have no citizenship rights in the countries that are hosting them, let alone Israel, and are dependent on whatever support UNRWA is providing.

The question of the Palestinian refugees’ right to return is at the heart of the Palestinian question. It cannot be resolved under capitalism. Only a socialist revolution in the Middle East and the establishment of a Socialist Federation of all peoples with the right to autonomy for the minorities can allow the conditions for healing the wounds accumulated in decades. Only this will materially provide the basis (homes, resources, infrastructure, etc) for a settlement of the question that could satisfy all grievances without creating another monstrous oppressive system.

About 150,000 Palestinians remained on their land within the ‘Green Line’, the 1948 territory occupied by Israel. Today they make up more than 20 percent of the Israeli population. The Israeli state proceeded to expropriate the properties and land of those who escaped, using ad hoc laws, and systematically undermined the rights of the remaining Palestinians with laws such as the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law, the 1953 Land Authority Law, and others. In 1952, the Arab Israelis (the Palestinians within the Green Line) were granted formal citizenship with the 1952 Citizenship Law.

However, until 1966, the Israeli Palestinians were subject to martial law, and lived in a state of segregation with enormous restrictions on their mobility, which allowed the Israeli authorities to expropriate the property even of those Palestinians who were internally displaced, but physically prevented from going back to their homes.

In a matter of a few years, the 550 Palestinian villages that had survived the Nakba had been reduced to 100. More than 25 percent of the Palestinian peasants saw their land expropriated and had to take refuge in ‘ghost’ villages, considered illegal by Israel and therefore periodically cleared by the army and razed to the ground, only to be rebuilt later. Their location has been expunged from the maps.

After 1967, the Israeli government eased the pressure on the Palestinian citizens, attempting greater integration of the Israeli Arabs, while consolidating the new territorial conquests of the Six Day War: the Occupied Territories of the West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem.

Consolidation of Israeli capitalism

For the Palestinians, Israel represented a hostile regime, usurper of their land, responsible for genocide and mass deportations. For the Jewish refugees who continued to flow in from Europe after the Shoah, and the Arab world, where centuries-old balances of coexistence had been broken by the telluric impact of the Nakba, making it impossible for hundreds of thousands of Jews to stay – Israel became increasingly the best chance to rebuild lives destroyed by war and persecution.

Between 1948 and 1951, Israel’s population more than doubled (from 650,000 to over 1,400,000), and continued to grow rapidly in the following decades, thanks to Jewish immigration. Israel’s population reached over three million in 1978, and today has crossed the nine million mark.

The Israeli Zionist bourgeoisie and imperialism were able to exploit with remarkable cynicism the determination of the Jewish masses to build what they regarded as a safe haven against persecution. During the 1950s and 1960s, they exploited the mass of Jewish refugees as a convenient and ever-renewable cheap labour force for their industries and, if necessary, as soldiers to ensure Israel’s supremacy over the region. The remarkable development of Israeli capitalism could not have happened, however, without major US subsidies and investments (estimated at $140 billion by the mid-1990s, since 1949).

Despite the considerable influx of immigrants, as the years went by, an increasing share of Israeli Jews were born inside Israel: 27.7 percent in 1949, 44 percent in 1968, 57 percent in 1981. Today, the Israeli-born Jews are 75 percent. The Hebrew language, designed by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda at the end of the 19th century, took root more and more among the younger generations, gradually replacing the Yiddish of the Ashkenazi and the Ladino of the Sephardim. Many second-generation Israelis dropped the languages of their countries of origin.

The Jewish masses were of course impervious to the nationalist propaganda of the Arab regimes, which depicted them indiscriminately as enemies that needed to be crushed. The continuous military threat posed by neighbouring Arab regimes and the tactics of individual terrorism adopted by the Palestinian nationalist organisations since the mid-1960s drove the majority of Israelis into the arms of the Zionist state. This helped Zionism shape an Israeli national consciousness, based on the fear that the Arabs wanted to destroy them.

The economic boom of the 1950s-1970s, amplified by US aid, meant that Israeli workers (including to a certain degree the Arab-Israeli minority) were able to reach a considerably higher standard of living than the Arab masses in the neighbouring countries. These material conquests represented for the Israeli workers a capital to be defended, especially when threatened by external attacks.

Among Israel’s Palestinian minority, though subject to heavy discrimination, many were also aware of the bleak landscape of misery offered by the autocratic and reactionary Arab regimes.

The Saudi monarchy, Kuwait, Qatar, the UAE and the rest of the oil-rich Gulf countries, while professing to be ‘friends’ of the Palestinians and financing the PLO, relied on hundreds of thousands of Palestinians and other poor migrant workers to work in conditions of semi-slavery. However, they were careful not to grant them political or trade union rights, let alone citizenship rights, and exploited them ruthlessly.

This went on until the early 1990s, when the impact of the first Gulf War advised these regimes to discard the Palestinian workers and look towards India, Pakistan and Nepal as their main source of cheap labour.

Class contradictions within Israel

Not forgetting these fundamental factors which guaranteed a certain base of support for Israeli capitalism, especially when under threat, it must be said that Israeli society was and remains deeply polarised and far from homogeneous.

In 1974, a government inquiry was triggered by the violent protests in the early 1970s of the Israeli ‘Black Panthers’. These protests had been harshly repressed by the Zionist state. The inquiry looked into the condition of the Sephardic Jews (mostly settling in Israel after 1948 from North Africa, Iraq, Yemen and the rest of the former Ottoman empire), which represented half of the Jewish population of Israel.

The report revealed the existence of a poor and exploited ‘second Israel’. Of Sephardic origin were 92% of the children with malnutrition problems and 90% of the Jewish prison population; their high-school education rate was only 17 percent while for Jews of European origin (Ashkenazis) it was 41 percent; in universities, Sephardic youth were 20 percent of the total, as opposed to 78 percent Ashkenazis.

The Sephardic social composition was 62 percent working class (against 39 percent) and only 5 percent bourgeois (against 14 percent). This, alongside many other statistics, showed the deep divisions within Israel itself. The radical rebellion of the Sephardic youth in Israel against oppression and discrimination was not by chance inspired by the Black Panthers’ struggle in the USA.

Israeli capitalism has become increasingly unequal over the past decades. In 1992, the richest 10% of the population appropriated 27% of the national income, while the poorest 10% held only 2.8%. (CIA, The World Factbook 1999).

Inequality has enormously increased since then. According to the World Inequality Report 2022, published by The World Inequality Lab:

“Israel is one of the most unequal high-income countries. The bottom 50% of the population earn on average €PPP 11,200 or NIS 57,900, while the top 10% earn 19 times more (€PPP 211,900, NIS 1,096,300). Thus, inequality levels are similar to those in the US, with the bottom 50% of the population earning 13% of total national income, while the top 10% share is 49%.”

Israel’s economic and military might has been built on the exploitation of the Israeli and Palestinian working class to no lesser extent than in any other capitalist country. In fact these figures show what happens when the working class is so effectively divided.

The Israeli state is founded on the oppression and systemic discrimination of the Palestinians, but this has just meant continuous exploitation of Palestinians and ordinary Israeli workers, while the Israeli capitalists have accumulated fortunes.

Turning point of the Six Day War

The year 1967 was a watershed in Middle Eastern history / Image: Government Press Office Israel

The year 1967 was a watershed in Middle Eastern history / Image: Government Press Office Israel

The year 1967 was a watershed in Middle Eastern history. Until then, the majority of Palestinian refugees in the various Arab countries had nurtured the hope that the intervention of the armies of Egypt, Syria and Jordan would one day guarantee the reinstatement of the rights of the Palestinians.

At dawn on 5 June, after a month of skirmishes and tensions, the Israeli Air Force unleashed a lightning strike attack against the Egyptian and Jordanian airports, destroying more than 90 percent of both countries’ military aviation before the planes could even take off. On the same day, the IDF invaded the West Bank and Gaza and, in a couple of days of fierce fighting, defeated the Jordanian Arab Legion and the Egyptian army stationed in Gaza.

On 6 June they conquered Gaza, and the next day they took Jerusalem, completing the occupation of the West Bank. On 10 June, while the Arab world was stunned, Israel had not only unified the entire British Mandate Palestine under its rule but had occupied the Syrian Golan and the Egyptian Sinai, inflicting a momentous defeat on its Arab enemies, and causing a new wave of 300,000 Palestinian refugees.

The disastrous defeat in the Six Day War, however, did not have the same demoralising impact the Nakba had on the Palestinian people; this time it was anger that prevailed over demoralisation. The Arab defeat had the effect (totally unforeseen by the Zionist strategists) of wiping out any residual illusion that an external intervention would ‘set things right’.

The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) had been set up in 1964 by a decision of the Arab Summit. For the first years it was nothing more than an appendage of these regimes. It encountered growing opposition from forces arising from the Palestinian Resistance, like Fatah, Yasser Arafat’s guerrilla organisation, and those who, like him, had had the chance to experience the prisons of the ‘friendly’ regimes in the early 1960s. In 1967 the formation of George Habash’s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) reflected the underlying radicalisation of the Palestinian struggle.

Arab bourgeois nationalism was totally exposed and discredited by the crushing defeat in the Six Day War. Among the Palestinians, who suddenly found themselves under direct Israeli domination, and among all those who crowded the refugee camps in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon, there developed a fertile ground for criticism of Arab nationalism and the Arab regimes. This ferment gave enormous impetus to the Palestinian Resistance (especially Fatah and the newly formed PFLP), which soon gained a mass base in the refugee camps.

On 21 March 1968, the Israeli army set out to attack the Resistance headquarters in the village of Karameh in Jordan. The Fatah fighters, warned of the attack, held the ground. The IDF did not expect to find such a level of resistance and had to retreat. 28 Israeli soldiers were killed and 69 wounded.

More than a hundred Palestinian fighters were killed, but this episode aroused a huge emotional wave throughout the Arab world because the Palestinian resistance had succeeded where the armies of the Arab states had always failed: to defeat the Israeli army for the first time. This propelled Fatah and Arafat to the top of the embattled PLO in February 1969.

Arab regimes undermined by the Palestinian Resistance

The Palestinian refugees were relegated to the misery of the overcrowded refugee camps. Their population reached one and a half million in 1968. The refugees were used by the capitalists of the various countries as cheap labour, subjecting them to humiliating conditions. But the rise of the Resistance in the late 1960s restored the Palestinians’ pride, turning the camps into sanctuaries for the organisations of the Resistance.

This exposed the camps and the host countries to violent Israeli reprisals. The constant friction between the Resistance and the governments of the host countries was aggravated by the spread of revolutionary ideas among the Palestinians, many of whom conceived the Palestinian revolution as part of a more general Arab revolution with a socialist character. These positions, bolstered by the growing prestige of the Palestinian Resistance, resonated with the Lebanese and Jordanian masses.

The first crisis exploded in 1969 in Lebanon, already deeply fractured by tensions between the Christian-Maronite minority. Frictions between the Resistance and the Lebanese government degenerated in the autumn of 1969 into several days of bitter fighting in which the Lebanese army came off on the losing side. The Cairo agreement put a temporary end to the confrontation.

Black September

A similar process had been underway for some time in Jordan. The growing revulsion at the close ties between Hussein’s Hashemite monarchy and US imperialism, combined with the oppressive conditions faced by the vast majority of the population, resonated with the prospect of a Palestinian revolution.

The PLO tried hard to avoid a head-on clash with King Hussein, but the revolutionary rise of the Jordanian masses overwhelmed every obstacle. The mass movement confronted the Jordanian regime with no real leadership due to the PLO’s hesitations.

Starting in the summer of 1970, a series of clashes between Palestinian resistance fighters and the army had escalated. A series of hijackings of airliners (PanAm, Swissair and British Airways, without civilian casualties) by the PFLP was the excuse Hussein sought to justify the repression to an international audience.

The Palestinian resistance got the upper hand and conquered a large part of the capital Amman in a couple of weeks. Hussein appointed a military government on 16 September, which, at dawn the next day, unleashed an offensive against the Palestinian refugee camps.

Bedouin army units (less infected by the revolutionary mood) under the command of General al-Majali bombarded the camps with phosphorus and napalm shells and deployed tanks against the working-class neighbourhoods of Amman. Despite the disproportion of military forces, the resistance was so fierce that the fighting lasted almost another two weeks, forcing Hussein to seek an agreement on 27 September 1970. The Palestinian resistance accepted to leave Jordan and move to Lebanon.

The exact number of the victims of the Jordanian ‘Black September’ has never been known. Palestinian sources speak of 20,000 killed, other sources of 5-10,000, mostly among the civilian population.

The attitude of the PLO leaders and Arafat was harshly criticised by a very large sector of the Palestinian revolutionary movement, which had come out of the Jordanian events in tatters. Frustration and anger at the massacre perpetrated by Hussein and the silence of the other Arab nations were rampant among the Palestinians, leaving room for the development of extreme terrorist formations, such as the founding of the terrorist group Black September.

PLO’s diplomatic turn

The Jordanian defeat did nothing to overcome the fundamental limitations of the Palestinian resistance. The conception of a liberation struggle ‘brought from outside’ assigned the Palestinian masses of the Occupied Territories a merely passive role. The PLO’s commitment to the policy of ‘non-interference’ in the internal affairs of the Arab states was paradoxically reinforced.

The idea that the liberation struggle should be achieved by the Palestinian people themselves was abandoned / Image: public domain

The idea that the liberation struggle should be achieved by the Palestinian people themselves was abandoned / Image: public domain

The limitation of the struggle to a purely national framework, postponing to a later date the problem of what kind of society to build in liberated Palestine, had allowed the PLO to preserve a false unity with the Arab regimes, but could never protect it from betrayal by those same regimes. Whenever the Arab masses had attempted to free themselves from their chains and the Palestinian struggle had collided with the fundamental interests of their oppressors, they were betrayed.

Under Arafat’s leadership, the PLO had eventually conquered mass support among the Palestinians. However, faced with international diplomatic pressure, particularly from Arab regimes, Arafat imposed a 180-degree turn: the idea that the liberation struggle should be achieved by the Palestinian people themselves was abandoned in favour of a conception of the armed struggle as a way to ‘put pressure on’ in international diplomacy.

On 6 October 1973, on the eve of the Jewish festivity of Yom Kippur, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. The Israeli defence apparatus was caught unawares and suffered a heavy blow. The Palestinian resistance took part in the fighting in the Occupied Territories. Jordanian, Iraqi and Moroccan units and a symbolic Tunisian detachment also participated in the war. Initial successes by the Arab forces redeemed the ignominious defeat of 1967 in the eyes of the Arab masses.

The Yom Kippur War had a profound impact on Israeli society by shattering the confidence in the invincibility of Israel’s army. However, the IDF would eventually reorganise and make up for the lost ground and on 22 October an armistice was reached at a point when Israel had already regained the upper hand.

The ‘diplomatic turn’ was strengthened. The PLO was recognised by the Arab Summit as the ‘sole and legitimate representative of the Palestinian people’ on 27 November 1973.

Amendments to the Palestinian National Charter in May 1974 introduced for the first time the prospect of a partial liberation of Palestine (and the implicit recognition of Israel).

Arafat was invited to deliver a speech at the United Nations on 13 November 1974. In his famous address, he condemned Zionism, but said, “Today I have come bearing an olive branch and a freedom fighter’s gun. Do not let the olive branch fall from my hand.”

Arafat’s turn allowed the treacherous Arab regimes to gain the initiative again, a line pursued even at the cost of undermining the only source of real strength of the Resistance, the roots of the movement among the Palestinian masses.

Revolution and counterrevolution in Lebanon

Despite the Jordanian experience and the clashes of 1969, the Palestinian resistance in Lebanon grew confident of its ever-expanding strength. Lebanon was riven by deep divisions between the Christian-Maronite ruling class installed by the French and the various Muslim bourgeois and petty bourgeois factions.

As in Jordan, the growth of the authority of the Palestinian resistance went hand in hand with the rise of revolutionary sentiments among the Lebanese masses. The Palestinians in the refugee camps had become an integral part of the Lebanese working class.

The Lebanese capitalists had been exploiting their labour for years, relocating the camps near the cities, and had attempted to use the refugees to undermine the strong organisations of the Lebanese working class. This cynical calculation, however, soon led to a welding together of the Palestinian liberation movement and the revolutionary aspirations of the Lebanese workers.

The forced relocation of thousands of PLO fighters from Jordan, inevitably converted Lebanon into their main base. Entire neighbourhoods of Beirut were controlled by the PLO, which was emerging as an alternative power to the state, while enjoying wide support among the Lebanese masses. Thanks to funding raised in support of the Resistance, numerous social institutions, schools and hospitals had flourished around the PLO, often offering higher quality support than what was made available by the Lebanese state. The access to all these institutions was open to the whole population.

In the mid-1970s, the fragile balance broke down. A ‘civil war’ was unleashed by the Christian-Maronite ruling class, the army and the Christian Phalangist militias and their allies. This was in reality a counter-revolutionary class war, to reassert their control over society. The Lebanese masses and their organisations, such as the Lebanese National Movement led by Kamal Jumblatt, as well as the Palestinian resistance, had to be smashed. Israel intervened with frequent incursions into southern Lebanon to hit the Resistance.

On 26 January 1975, Palestinian fighters intervened in defence of the Sidon fishermen’s strike against attempted repression by the army. The Palestinian resistance forced the men of the Lebanese security forces to retreat, leaving ten killed on the field.

The Christian Phalange invoked an iron fist against the PLO. In February, a pro-Palestinian Lebanese MP, Maarouf Saad, was shot dead, reportedly by the Lebanese Army. On 13 April, an assassination attempt on Phalangist leader Pierre Gemayel triggered an immediate reprisal by the Phalangists who blocked a bus heading to the refugee camp of Tall el-Zaatar and massacred all 27 passengers in cold blood, sparking fighting throughout Beirut.

For the whole of 1975, the PLO’s attitude was to limit itself to assisting the militias of the Lebanese Left with logistic support and arms. The PLO’s ‘wait-and-see’ tactic served merely to prolong the conflict, but the Phalanges’ decision to besiege the refugee camps of Dbayeh and Tall el-Zaatar forced the Palestinian armed resistance groups to enter the conflict with their full weight. The counterrevolutionary Phalangists were chased into the mountains until they were on the verge of defeat. At this point a spectacular reversal of positions took place.

At the announcement of the possible establishment of a revolutionary government of the Lebanese left, the Arab front of the ‘friends’ of the Palestinian struggle buckled. Egypt and Jordan were frightened by the prospect of revolution spreading throughout the Middle East. However, the open betrayal came from where it was least expected. The champion of the anti-imperialist struggle Hafez al-Assad, Syria’s Baath president, carried out a spectacular u-turn, sending Syrian troops to support the Phalangists in June 1976.

The Syrian intervention brutally tipped the scales. The Resistance had to retreat to the cities at the cost of heavy losses, while the Phalangists, protected by the Syrian army, laid siege again to the camp of Tall el-Zaatar. After 52 days, on 12 August, Tall el-Zaatar surrendered and the Phalangists and Syrians took their revenge by massacring three thousand Palestinians while they were evacuating the camp.

The most ‘progressive’ of all the Arab regimes, Syria, when threatened even if indirectly by the development of revolution, had not hesitated to side with the most reactionary wing of the bourgeois counterrevolution against the same Palestinian Resistance whose headquarters it hosted in Damascus and had financed for years.

The ruling cliques of the Arab League stood at the window watching without lifting a finger, relieved. After 19 months of war and 60,000 killed, Lebanon was divided into zones where the different contenders entrenched their positions in a fragile armed truce. Despite Assad’s betrayal, the leadership of the PLO spent itself in humiliating negotiations to patch up the rift and recompose the ‘Arab front’.

Israeli invasions of Lebanon

For Israel the very presence of Palestinian fighters on Lebanese soil was intolerable. On 14 March 1978, Israel invaded South Lebanon and within days overwhelmed the Palestinian resistance (abandoned by the Lebanese army).

However, the then Prime Minister, Begin, decided to withdraw under pressure from US president Jimmy Carter, who had decided to support bilateral secret negotiations between Sadat and Begin. These were aimed at normalising the relations between Israel and Egypt. A deal was formally ratified at Camp David on 18th September 1978.

For Israel, however, the problem was not resolved. On 6 June 1982 the IDF launched a second large-scale invasion of Lebanon under the command of Ariel Sharon, the defence minister in the Begin government. The invasion turned into a bloodbath. In a matter of hours, a deluge of fire from the Israeli Air Force fell on the cities and refugee camps, while columns of tanks advanced on Beirut, leaving behind a trail of death and destruction: 14,000 casualties just in the first two weeks.

The IDF besieged West Beirut in a deadly embrace that lasted 78 days, during which all supplies were blocked and the city was relentlessly bombarded. 7,000 Lebanese civilian deaths and an unspecified number of Palestinian casualties (of which a true tally will never be made) were not enough to break the resistance.

The stalemate allowed imperialist diplomacy to come into play and negotiate the complete evacuation of the Palestinian resistance from Lebanon. At the end of August 1982, more than 10,000 Palestinian fighters evacuated Beirut under the watchful eyes of a Franco-Italian-American force, but the price paid for preserving the PLO structures was extremely high.

The Lebanese population and the tens of thousands of Palestinians who continued to crowd the refugee camps were left at the mercy of the phalangists, the pro-Syrian Shiite militias of Amal, the Syrian army and the Israeli army, with the sole guarantee of a pact written in the sand that no one had any interest in respecting.

Israeli revenge was immediate and terrible. Between 16-18 September, as soon as the international ‘peace’ contingent had left Lebanon (after disarming and evacuating the remaining Palestinians fighters), the Lebanese Phalangists, protected by the IDF, massacred 3,000 defenceless Palestinians refugees by ravaging the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut for 40 hours.

Ariel Sharon reportedly observed the operation from the top of a building, 200 metres from the wall of the Shatila camp. Just like the Syrians had done six years earlier at Tell al-Zaatar, the Israeli army merely provided logistical support to the phalangists, illuminating the area with flares, blocking all escape routes from the camps, and feeding and assisting the Phalangists who were carrying out the massacre.

The impact of the massacre at Sabra and Shatila sent shockwaves through society, even reaching Israel. On 25 September 1982 a mass demonstration of 400,000 flooded the streets of Tel Aviv in revulsion against the IDF’s and Sharon’s role in the massacre. An official inquiry was set up to defuse the movement and cover up the IDF’s role, but even the report of such an inquiry could not hide the personal responsibility of Ariel Sharon, who was forced to resign.

The leadership of the PLO moved to Tunisia, where Arafat and his entourage lived in gilded exile until they moved to Gaza in 1994. All their energies were devoted to devising negotiating strategies and juggling rivalries among the Arab regimes, as well as re-establishing normal relations with the Gulf monarchies.

The PLO’s policy became increasingly based on trading off stabilisation in the Middle East for concessions. In order to gain leverage at a negotiating table in the eyes of US imperialism and Europe, Arafat would be relying on the Resistance and even increasingly on individual terrorist tactics (formally condemned by the PLO), as the power of the mass resistance movement receded after the defeat.

Occupied Territories on the eve of the Intifada

During twenty years of military occupation, the Territories had been for Israel an additional market for its products and a source of unskilled labour. An important factor in the decision to occupy the West Bank and the Golan Heights had been the appropriation of the region’s water resources. The last thing Israel wanted was for the Territories to develop a life of their own.

The Israeli government engineered a gradual strangulation of the occupied territories’ economy, which was predominantly tied to agriculture, with limited small-scale handicraft. This undermined the livelihood of peasants and agricultural labourers, who were forced to swell the ranks of the 120,000 Palestinians who commuted on a daily basis to work in Israel (one third of the West Bank’s labour force and 50 percent of Gaza’s). The need to cross the ‘Green Line’ was used by the Israeli state as a weapon of reprisal against Palestinian workers, with constant threat of a border closure at their whim.

The economy of the Territories was (and still is) completely dependent on Israel even for basic consumer goods. Israeli policy exacerbated the natural and historical economic interdependence of the Territories with the rest of Palestine. In 1970, 82 percent of imports were already of Israeli origin, rising to 91 percent in 1987.

The hundreds of thousands of Palestinians abroad also fuelled a flow of remittances to their families, amounting to 37 percent of the Territories’ GDP at that time. Remittances continue to represent a significant portion (about 20 percent) of the GDP of the West Bank and Gaza even today. This paradoxically helped sustain a market to which Israeli production surpluses could be exported.

During the first ten years of occupation the total number of settlers did not exceed 7,000. However, with the rise to power of the Zionist right-wing Likud in 1977, the colonisation policy rapidly escalated. Over the following ten years, 18,000 homes and 139 settlements were built on Palestinian land, to host a total of 80,000 settlers. A network of special roads was set up to separate the settlers from the Palestinians, with the effect of severely limiting their freedom of movement. The growing presence of the Jewish settlers became the most odious manifestation of the occupation.

The Palestinian population of the Territories had experienced a remarkable demographic explosion during the twenty years of occupation. In 1987, 75 percent of the population was under 25 years old and 50 per cent even under 15. The majority – on the eve of the Intifada – had known nothing but the increasingly intolerable, humiliating and oppressive regime of the Israeli occupation.

Intifada

Four decades after the Nakba and twenty years after the Six Day War, the outlook for the Palestinian national struggle was bleak. The revolutionary movements in Jordan and Lebanon had been suppressed in blood, and the Palestinian resistance shattered. The enormous sacrifice by the Palestinian masses in the refugee camps had yielded no concrete result. Israel had consolidated its grip over the whole of Palestine.

The yawning gap between the PLO leadership in Tunis and the reality of the Territories had become so large that numerous signs of a change of mood on the ground had not been detected even by the usually perceptive Arafat.

A few months before the Intifada, a report by the West Bank Data Base institute of the Israeli sociologist Meron Benvenisti noted:

“Violence is increasingly the work of disorganised, spontaneous groups… Between April 1986 and May 1987, 3,150 violent incidents were recorded, ranging from the simple throwing of stones to roadblocks, and a hundred or so assaults with explosives or firearms.”

The increasing militancy of the Palestinian population under occupation was shown on 5-6 June, when a general strike greeted the anniversary of 20 years of Israeli occupation.

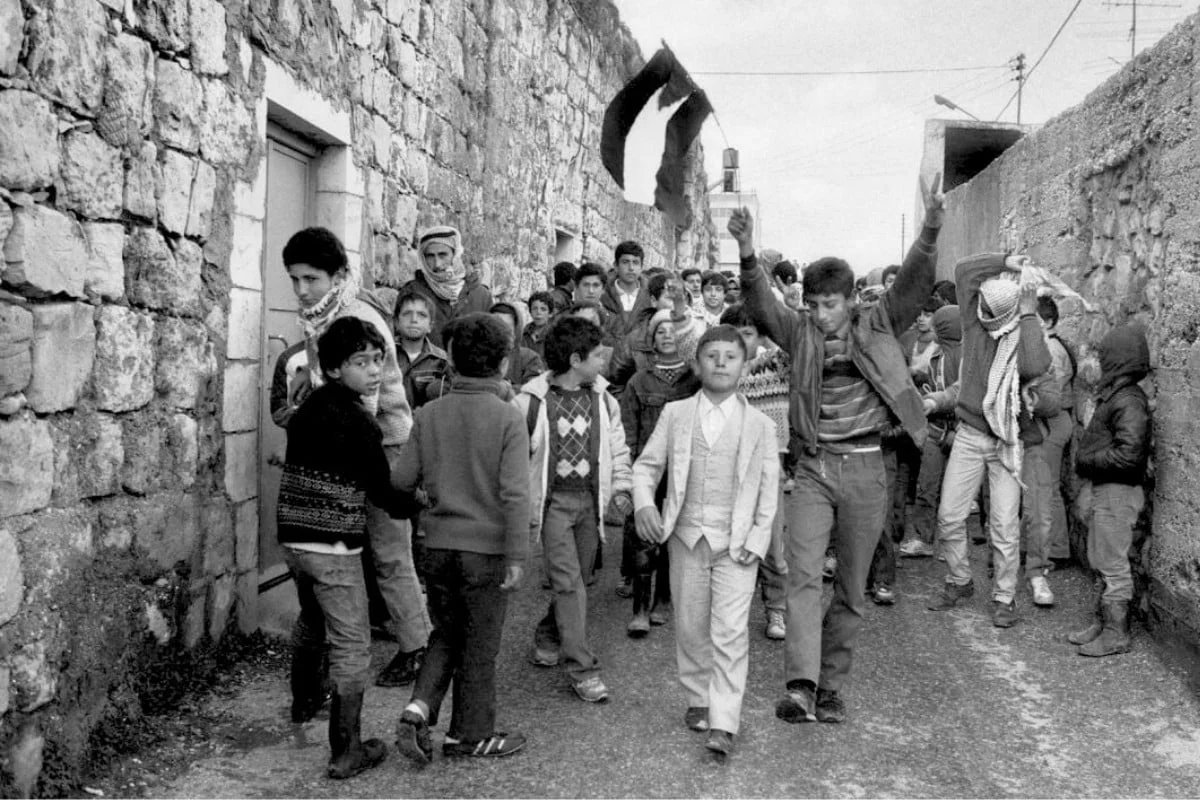

The word Intifada (a concept that can be translated as ‘shaking off’) well describes the reaction by the Palestinian masses / Image: Abarrategi, Wikimedia Commons