[Niklas Albin Svensson, marxist.com – 16 October 2025]

The financial markets are booming like never before. After a few jitters in April as Trump announced his ‘reciprocal tariffs’, the stock markets have hit record after record. This at the same time as workers are being squeezed, government finances are in crisis everywhere, central banks are failing to curb inflation, and unemployment is rearing its ugly head. Something doesn’t add up.

The rally in the stock market is based on AI, and pretty much only AI. It is the big tech companies that are leading the way. Stocks related to AI account for 80 percent of the rally this year. Speculators are betting big that this AI craze is going to deliver big results.

Goldman Sachs has come out defending the bubble, explaining how this is not like the bubbles of the past, because, they say, the profit rates are high and the balance sheets of the companies involved are good (i.e. they are sitting on tonnes of cash).

But it’s pretty obvious that the valuations are out of this world. Buying shares is like buying a share of the future profits of a company. Therefore, it should reflect the potential for the company to make profits in the future. As a result, the bourgeois use a value called P/E as the closest thing to an objective comparison between different companies. It’s the ratio of price over earnings, or the stock market valuation divided by the profits of the company.

One economist, Shiller, created a P/E index for the S&P 500 stock index, called the Shiller P/E. Historically, it has fluctuated between 10 and 20. Previous peaks of the index include 1929, just before the Wall Street Crash, when it hit 31 (price being 31 times higher than earnings), and 1999, just before the so-called DotCom bubble burst, when the index reached 44.

Now, the index has reached 40. In other words, the top 500 companies listed on the US stock exchange now have shares worth 40 times their annual profits, on average. This means that the expected growth of profits of these 500 companies is four times as high as in 1949, on the eve of the postwar boom, when the P/E ratio was 10.

For some companies, this figure is even more extreme. Tesla, which seems to attract particularly speculative investment, is at 240, meaning the company’s profit would have to be six times higher even to get to the point of being valued at the same rate as other companies. Nvidia is trading at 60 times their earnings. Palantir, the company that sells AI to government agencies, is trading at 700 times its earnings. Microchip producer ARM is at 250 times, etc.

No doubt these companies are capable of growing. But the idea that they will make profits in any way commensurate with their stock prices is clearly an absolutely ridiculous proposition. We can understand why, therefore, the Bank of England, as well as Jerome Powell, the head of the Federal Reserve, have urged caution. The Bank of England said that valuations “appear stretched, particularly for technology companies focused on artificial intelligence”, and noted how they compared to valuations during the dotcom bubble. JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon echoed the same sentiment, saying he was “far more worried than others” about the risk of a crash.

The investment bank Morgan Stanley is similarly questioning the soundness of deals that are being made. It points in particular to the latest deal in which Nvidia is funding the purchase of its own chips. It has agreed to fund a new company that is to buy Nvidia chips and then rent them out to X’s new AI startup. If these kinds of deals are what is driving demand, it is clearly unsustainable.

However, this hasn’t stopped Goldman Sachs economists from denying there is a bubble. Other commentators have followed suit. Their argument is an interesting one, also from a class point of view.

They are saying that the high valuations are justified by the high profits that have been made in the past period and that are still being made. They cite the fact that large corporations have a lot of cash. Google (Alphabet Inc.) is sitting on $95 billion. Investment company Berkshire Hathaway, led by Warren Buffett, is sitting on $340 billion. Apple has $160 billion, Amazon $93 billion and so on. The 13 top companies together are sitting on hoards of cash worth $1 trillion.

Google’s profits last year were a record $100 billion, which was a margin of 30 percent, i.e. for every ten dollars of income, three dollars were profit. Nvidia, which has had a virtual monopoly on the processors used to run AI models, is making a very nice profit margin of 75 percent, or $80 billion. No wonder they are keen on artificially inflating demand for their processors!

It isn’t just the tech companies that are swimming in money. General Electric is making a neat profit margin of 19 percent. The car industry can’t quite achieve such high numbers as the tech sector, but General Motors still made $15 billion with a profit margin of 8 percent.

In a sense, then, one can see where Goldman Sachs is coming from. Why shouldn’t the stock market boom when profits are good? The key here is that stock market valuations will be based, in the long term, not just on a feeling that everything is going really well, but on future profits. That is, only if these companies invest, expand production and thereby multiply their profits many times over, can the present stock market valuations be justified. But all indications are that this is not taking place.

Where is the investment?

For the past few decades, we have been told that what we need to do is to shower the big corporations with money to help growth. Economists and politicians correctly point out that it is investment that drives growth. And the only way, they say, to get this investment is to make the corporations more profitable.

They slashed wages and forced workers to work longer and harder, privatised state-owned companies, outsourced public services, cut taxes on wealth and on corporate profits, raised taxes on the poor, cut unemployment benefits to make workers more desperate for work. All of this, in the name of ‘growth’ or increasing investment. But after decades of making the corporations more profitable, we are entitled to ask: where is the investment?

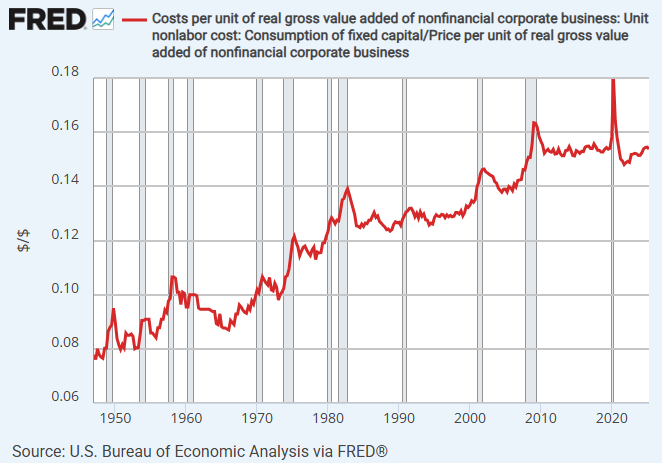

Investment has stagnated at around 14 percent of GDP. Investment in fixed capital (machinery, buildings etc) as a proportion of the value of each product (for which the price is the best approximation) has also been stuck at around 15 percent. Marx used this measure, among others, to measure the development of machinery in production. It can be calculated by taking the cost of capital for each product and dividing it by the sales value. This value was growing for a whole historical period, until the crisis of 2007-8.

Corresponding to this, there has been a decline in the ratio of fixed capital (machinery, etc) to wages. Taken together, these figures show that the capitalist class is no longer increasing the amount of machinery that is being used in production. It has stopped developing the productive forces.

Whatever additional profits are made are not invested but merely piled up as cash reserves or handed back to shareholders as dividends or stock buybacks.

Productivity of labour in manufacturing in the US peaked in 2013. For all the talk about the wonders of robots and AI, they have yet to have an impact on productivity. Again, this tells the same story: no further investment in machinery, and therefore no rise in productivity.

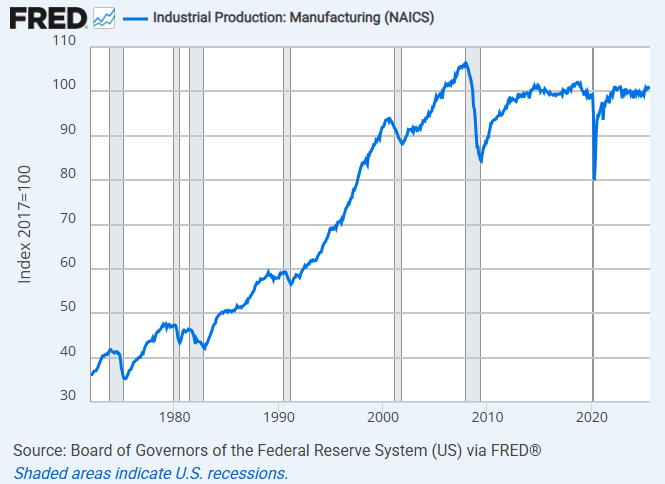

It is striking that manufacturing output in the US has fallen by 7 percent since 2007.

It almost seems that the level of investment in the economy stands in inverse proportion to the amount of profits being made. This ought not to be happening. According to the apologists of capitalism, the massive amount of profits ought to lead to a boom in investment. If lots of money is to be made, why not invest? Why not produce? Why not make our society richer?

A very similar argument has been pushed by a number of ‘Marxists’ who claim that the falling rate of profit is the cause of crises. If there is a lack of investment and the system is in crisis, it must be because the rate of profit is falling, they claim. Yet profit rates, at least by certain measures, have been higher for the past few years than at any point since the Second World War. On that basis, one would have thought we were on the verge of a major boom.

So, why aren’t the capitalists investing? Part of the explanation historically is that US businesses are investing abroad, with big US multinationals seeking higher rates of profit elsewhere. This is what Trump has been taking aim at. But again, this has not been the case over the past period. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) outflows from the US peaked at 3.6 percent of GDP in 2007 and have been falling since. Last year, they were only 1.1 percent.

If one attempts to approach the economy purely from the point of view of formulas, one can easily miss the obvious: there is no reason to invest if your factories are not running at even close to full capacity. This has been the case now ever since the crisis of 2007.

Capacity utilisation in industry is presently around 77 percent, which is significantly lower than the 87 percent it was at in the late 1960s. The question the CEOs will be asking themselves is: why build a factory that can produce more products when your existing factories are quite capable of fulfilling all your orders?

What we have here is thus a problem of the market that the companies are selling into, not a question of the profitability of the products they do sell.

When Marx discussed the rate of profit in Capital Volume 3, he didn’t just explain the tendency of the falling rate of profit and leave it at that. He also explained that there are countervailing factors. He deals with two which are of particular interest: 1. the cheapening of capital and raw materials through world trade, 2. the increase in the rate of exploitation. Both of these have been very much in force since the 1970s (when the rate of profit had actually fallen).

Globalisation was a key part of cheapening capital, raising the rate of profit, and also cheapening raw materials and all kinds of products that workers buy. Suddenly you could buy two or three TVs, or mobile phones, or cars, with a wage that could previously only buy one.

This was always one of the reasons why the industrial capitalists favoured free trade – it allowed them to keep wages down. In other words, it was possible to raise the rate of exploitation of the workers without them actually feeling worse off. The rate of exploitation is the amount of surplus value that workers create (their unpaid labour), over the wages they are paid.

Statistically, the increase in the rate of exploitation can be seen in the share of GDP that goes to wages, compared with the share of GDP that goes to profits. Every worker will be familiar with this: work harder with longer hours and receive less in return. Statistics show exactly the same thing: profits, including the rate of profit, have gone up at the expense of the working class.

What is the consequence of this? If workers are more exploited, and capitalist profits are gobbling up an increasing share of capital, and, to top it off, they aren’t investing these profits in new factories and machinery, then who is to buy the products that are being produced? This has been a chronic problem affecting the capitalist economy for decades. This is what they call the ‘lack of demand’ or ‘lack of purchasing power’.

When the bourgeois economists obsess about what they call ‘consumer confidence’, it is because this is a vital part of growing the economy. If the consumers don’t consume, the producers can’t sell, and if the producers can’t sell, they won’t invest.

Borrowing

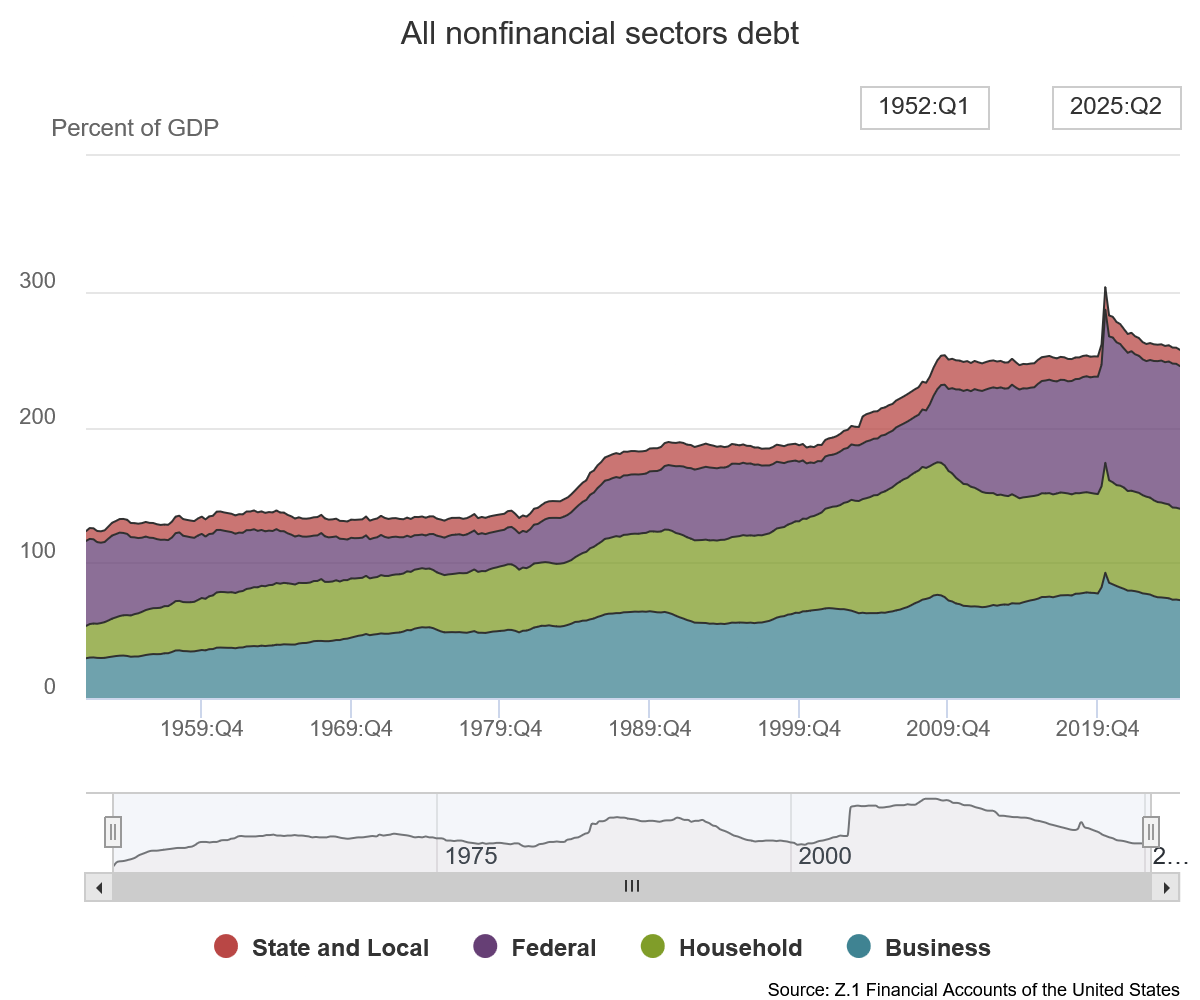

There are, of course, ways of getting around this problem. One of the ways of doing that is through consumer credit. It is therefore not an accident that a rise in the rate of exploitation, or a fall in wages relative to profits, has been accompanied by a rise in debt. That is, if the consumers can’t buy the product outright, lend them the money so they can.

Loans were traditionally used to buy houses, although in the past a much higher deposit was required. Nowadays, buying a car outright, even a used car, is the exception. And not just cars, but any kind of consumer goods. When getting a new kitchen, fridge or sofa – buy it on a repayment plan. Mobile phones tend to be sold on credit. Of late, Klarna and similar companies have worked out how to make money from small online purchases. Now you can even buy that drill or piece of clothing on credit and have the company deduct it from your balance for the coming 3-12 months.

Governments for decades have been consciously pushing more and more credit to keep the wheels of the economy going, by abolishing regulations against lending, by lowering interest rates.

But borrowed money isn’t the same as money you own. Everyone knows that a wage is yours to keep, but a loan you have to pay back. A loan is a claim on your future earnings, so the more you borrow, the less money you will have left every month. There is, in other words, a limit to how much you can borrow, in relation to how much you earn.

After 2008, particularly in the US, the limit of this credit expansion was reached. Since then, average household indebtedness, as a share of GDP, has decreased from 98 percent to 68 percent. The fact that US households didn’t take on more debt and thereby restricted their consumption would have had a depressing effect on the economy, if it hadn’t been for the fact that the state stepped in.

On the one hand, the central bank (Federal Reserve) printed virtual money to buy debt on an unprecedented scale – so-called ‘quantitative easing’ – and it left the federal funds rate (the rate at which banks lend to each other) at zero for nine out of the past 17 years.

On the other hand, the federal government picked up the slack. To keep up consumption, someone had to borrow, and if households weren’t able or willing to do so, then the government had to. It did so, through direct federal expenditure, or by putting more money in workers’ pockets through tax cuts and benefits. The US federal government debt increased from 65 percent to 105 percent, and it is continuing to increase at a rate that is unprecedented in peacetime. The US government has become the ‘consumer of last resort’, not just of the US but, incidentally, also of the world.

If one looks at the graph of, on the one hand, the levelling off of debt (as a share of GDP), and on the other hand, the levelling off of industrial production, it is abundantly clear that the inability to expand credit has led to a corresponding inability to expand industrial production. That is, the market on which products could be sold is no longer expanding. Hence, overcapacity in industry remains endemic and no new investment is being made.

The lack of a market is also the reason for protectionism. As competition for markets gets more intense, capitalists try to shield their market from competition. Note, for example, the ban on Huawei telecoms equipment, or the tariffs on electric vehicles implemented by the US and Europe. Steel tariffs is another example, where overcapacity in the steel industry in China has caused a collapse in the world market price of steel, leading the US and Europe to introduce tariffs to protect its own steel manufacturing against Chinese competition.

Nvidia needs to find new buyers for their processors, after the Chinese government partially blocked them from the Chinese market. Hence the flurry of deal-making they have been involved in over the past few months. The arrangement where Nvidia is buying its own products, although not unprecedented, is essentially a tacit recognition that the market isn’t there. So, they are using their massive profits to boost the demand for their products.

Will the stock market keep booming?

To summarise, the last decades of attacks on the working class have driven up the rate of profit, but they have also created massive indebtedness, first of working class people, and later of governments. The limits of this manner of growing the economy have been reached, which is why we’re now facing stagnation and increased international tension.

Given that the profits of these companies remain high, could the stock market not continue to trundle along, breaking one record after another? The answer to that question would have to be, ‘no’. That’s the key to the ratio of price to earnings. A very high ratio means a very high expectation of future profits. That is, not an expectation that a company will continue to make a profit, but that their profit will rise, even exponentially.

For that to happen, they must sell more commodities, more stuff, and to do that they need an expanding market. But the market isn’t expanding, or, even if it is for certain sectors, it isn’t expanding in general. It is therefore impossible for these companies to live up to their expectations.

This is what makes these stock market valuations fictitious. There is simply no way that Tesla is going to increase its profits ten- or twenty-fold in the coming period. Tesla sold 700,000 vehicles in the US last year, out of a total US market of 16 million. For Tesla to tenfold its sales, when the market isn’t expanding, it would have to take more than half the market, not just of electric vehicles, but all light vehicles. It clearly won’t happen. Its valuation is completely divorced from reality.

Why is the stock market booming then? Ironically, it is precisely because there is no money to be earned in investing in productive activities. Companies are hoarding cash, they are not investing. They are handing back money to shareholders through dividends and stock buy-backs, or are engaged in mergers and acquisitions. This will all boost share prices but does nothing to create long-term growth.

The cheap credit provided by central banks have also flowed in a big way towards stock market speculation. Cheapening credit allowed banks and other corporations to borrow cheaply to fund not just productive investments but also their speculative activities.

Incidentally, this also shows how completely parasitic the ruling class has become. If the bourgeoisie had a historical justification for its existence, it was that it reinvested its profits back into production, that it developed the productive forces. Now, it is clear, it is no longer doing so.

So, even if the stock market valuation implies an impending boom, the real situation on the ground is completely different.

The market for newbuild housing has been in recession for some months. This is having a big impact on employment in construction which has taken a hit.

The job market is being seriously affected, particularly the unemployment rate for African-American workers, which worries economists. Capitalism uses groups like black and women workers as a reserve army of labour, and so when recession hits, they are the first to go.

Consumer sentiment, which the economists obsessively follow, has been in decline since 2024. This measurement offers a glimpse into what consumers, most of whom are workers, think about their economic prospects. Only those with large holdings in shares are relatively optimistic. The rest are feeling worse than they did at the height of the ‘great recession’ in 2009.

This situation has now led the Federal Reserve to start lowering interest rates, but this was a difficult decision for the governors. Inflation remains relatively high, and although US companies have swallowed the tariffs for now, they are expected to hit consumers with higher prices in the new year.

Tariffs are also likely to cause long-term problems for investment as capital (the physical kind, machinery, etc.) will become more expensive. They restrict competition from abroad, which will make US manufacturers less inclined to bring their factories up to the latest standards as they are insulated from the world market.

In the more immediate term, the US government expenses, like in many other countries, need to be brought in line with income. The present situation, with a 27 percent budget deficit, is clearly unsustainable when debt is already at 119 percent of GDP. Interest payments alone cost over $900 billion. When the day of reckoning comes and the government has to balance the books, whether by tax rises or spending cuts, it is going to hurt an economy that has become completely dependent on government financing.

The whole picture illustrates the organic crisis of capitalism, that the system is at a dead end and can’t take society forward. For the past decades, workers have had to swallow bitter pills of attacks in the hope that something will get better. Trade union leaders and political parties have been selling them this lie time and again. But it is becoming increasingly obvious that the medicine is doing nothing to cure the disease.

The only ones that have benefitted from the past 18 years of economic measures have been a tiny handful of parasitic billionaires whose wealth, buoyed by the stock market bonanza, has increased exponentially. And the rest of the world is paying the price.

Now, we are on the precipice of another recession, and nothing is a more striking indicator of that than the stock market. The more serious bourgeois commentators are getting worried.

All the tools they used to get us this far have been used up: governments have borrowed unprecedented amounts, central banks have cut interest rates and printed money. Nothing has solved the problem, and now we’re facing another downturn where governments are already heavily indebted, and central banks are hamstrung by inflation that won’t come down.

The bourgeois have postponed the evil day. They have attacked the workers, they have looted the state, whilst claiming ‘we’re all in it together’. None of it has helped. Now, it is starting to dawn on them that they will be next in line.